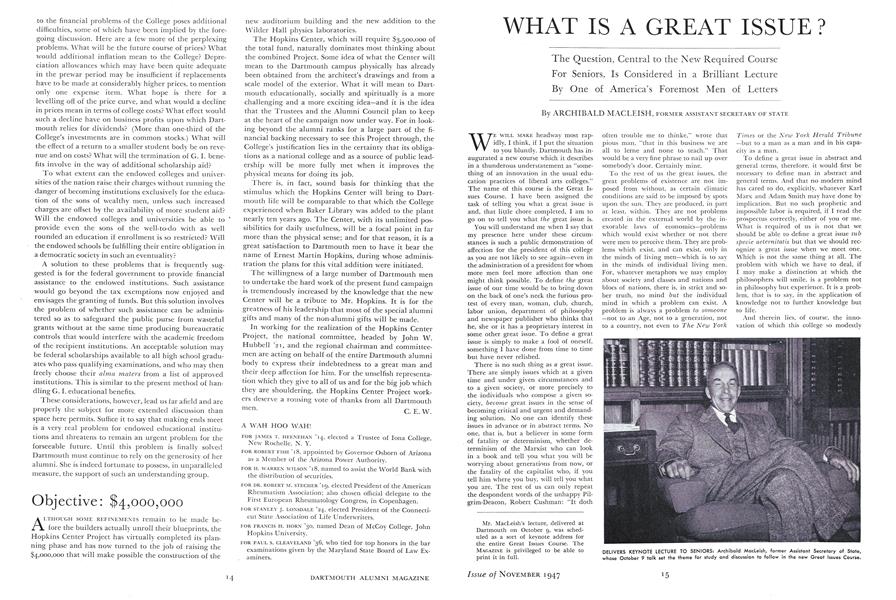

The Question, Central to the New Required Course For Seniors, Is Considered in a Brilliant Lecture By One of America's Foremost Men of Letters

WE WILL MAKE headway most rapidly, I think, if I put the situation to you bluntly. Dartmouth has inaugurated a new course which it describes in a thunderous understatement as "something of an innovation in the usual education practices of liberal arts colleges." The name of this course is the Great Issues Course. I have been assigned the task of telling you what a great issue is and, that little chore completed, I am to go on to tell you what the great issue is.

You will understand me when I say that my presence here under these circumstances is such a public demonstration of affection for the president of this college as you are not likely to see again—even in the administration of a president for whom more men feel more affection than one might think possible. To define the great issue of our time would be to bring down on the back of one's neck the furious protest of every man, woman, club, church, labor union, department of philosophy and newspaper publisher who thinks that he, she or it has a proprietary interest in some other great issue. To define a great issue is simply to make a fool of oneself, something I have done from time to time but have never relished.

There is no such thing as a great issue. There are simply issues which at a given time and under given circumstances and to a given society, or more precisely to the individuals who compose a given society, become great issues in the sense of becoming critical and urgent and demanding solution. No one can identify these issues in advance or in abstract terms. No one, that is, but a believer in some form of fatality or determinism, whether determinism of the Marxist who can look in a book and tell you what you will be worrying about generations from now, or the fatality of the capitalist who, if you tell him where you buy, will tell you what you are. The rest of us can only repeat the despondent words of the unhappy Pilgrim-Deacon, Robert Cushman: "It doth often trouble me to thinke," wrote that pious man, "that in this business we are all to lerne and none to teach." That would be a very fine phrase to nail up over somebody's door. Certainly mine.

To the rest of us the great issues, the great problems of existence are not imposed from without, as certain climatic conditions are said to be imposed by spots upon the sun. They are produced, in part at least, within. They are not problems created in the external world by the inexorable laws of economics—problems which would exist whether or not there were men to perceive them. They are problems which exist, and can exist, only in the minds of living men—which is to say in the minds of individual living men. For, whatever metaphors we may employ about society and classes and nations and blocs of nations, there is, in strict and sober truth, no mind but the individual mind in which a problem can exist. A problem is always a problem to someone —not to an Age, not to a generation, not to a country, not even to The New YorkTimes or the New York Herald Tribune —but to a man as a man and in his capacity as a man.

To define a great issue in abstract and general terms, therefore, it would first be necessary to define man in abstract and general terms. And that no modern mind has cared to do, explicitly, whatever Karl Marx and Adam Smith may have done by implication. But no such prophetic and impossible labor is required, if I read the prospectus correctly, either of you or me. What is required of us is not that we should be able to define a great issue subspecie aeternitatis but that we should recognize a great issue when we meet one. Which is not the same thing at all. The problem with which we have to deal, if I may make a distinction at which the philosophers will smile, is a problem not in philosophy but experience. It is a problem, that is to say, in the application of knowledge not to further knowledge but to life.

And therein lies, of course, the innovation of which this college so modestly speaks. The theoretical relation between the liberal arts curriculum and life is not new. It has been declared before this. Whether or not they put the matter in precisely these words, the general notion of the liberal arts colleges has been that where the rest of the educational apparatus aimed at livelihood in one form or another, the liberal arts college aimed at life. What is new in the Dartmouth proposal is the acceptance of a degree of responsibility for the realization of that theoretical relationship. When it came to the bridge between the liberal arts curriculum and the life for which it preparedwhen it came, that is to say, to the application of the curriculum to life—the liberal arts colleges have not, in the past, had much to say. They have acted, or they have appeared to act, as though the distinction between education for life and education for livelihood were a distinction not of a moral and intellectual, but of a wholly practical nature—a distinction which, like the distinction claimed by certain artists and poets, was chiefly important because it relieved them of responsibility for the consequences of their acts.

When pressed on this point, as the classicists and the mathematicians have been pressed at one time or another, the liberal educators have inclined to take refuge in the mysticism of the trade. Latin prepared a man for life in the world because it worked certain indefinable miracles in his mind, enriching it as the minds of certain British statesmen are thought to have been enriched by similar exercises. Mathematics hardened and tempered the intellectual muscles. The whole process, one gathers, was conceived of as something very like the training which a football squad went through at Yale in my day- long before the pragmatic practices in current use were introduced; You were carefully fed, carefully exercised, carefully disciplined and then turned loose on a football field where Percy Haughton's boys ran around you and through you and over you so fast that you went home with the conviction that Ned Mahan was twins. You had everything required of a football player except the ability to make use of what you had. You were fit, you were fast, you were strong—but you were fit, fast and strong in the wrong places at the wrong times and occasionally in the wrong direction.

One can understand and even admire that theory of football. It was football at its purest—football for football's sake. Also it was simpler to teach if considerably more painful to play. One can sympathize also with the similar liberal arts point of view about education. Education for education's sake is a noble ideal and far easier to practice—for the teachers at least—than the translation of the end results of education into the vulgar business of living. The monuments of unaging intellect, of which Yeats wrote in the most beautiful of modern poems, are peaceful and comforting neighbors to the soul and more than one great teacher must have felt his own heart whispering to him as he read:

"Once out of nature I shall never take My bodily form from any natural thing, But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make Of hammered gold and gold enamelling To keep a drowsy emperor awake; Or set upon a golden bough to sing..... "

Neither the bachelor of arts nor the teacher of the humanities nor even the greatest graduate of the liberal arts colleges can explain with precision, as any bachelor of business administration can explain to you in two sentences, just how the curriculum they have taught or studied prepares a man for the great world. There is a remarkable and unknown letter of Thomas Jefferson's, the only legible copy of which has long lain unpublished in- of all places—Teachers College at Columbia, which makes the point with the astonishing literalness and precision for which the great man is famous. It is a letter to which I shall wish to return for another reason. Here, with your permission, I shall quote the first few sentences:

Monticello June 18. '99.

DEAR SIR,

I have to acknowledge the receipt of your favor of May 14. in which you mention that you have finished the 6. first books of Euclid, plane trigonometry, surveying and algebra and ask whether I think a further pursuit of that branch of science would be useful to you. There are some propositions in the latter books of Euclid, and some of Archimedes, which are useful, and I have no doubt you have been made acquainted with them. Trigonometry, so far as this, is most valuable to every man, there is scarcely a day in which he will not resort to it for some of the purposes of commoti life. The science of calculation also is indispensible as far as the extraction of the square and cube roots. Algebra as far as the quadratic equation and the use of logarithms are often of value in ordinary cases: but all beyond these is but a luxury; a delicious luxury indeed; but not to be indulged in by one who is to have a profession to follow for his subsistence. In this light I view the conic sections, curves of the higher orders. Perhaps even spherical trigonometry, Algebraical operations beyond the 2d dimension, and fluxions. There are other branches of science however worth the attention of every man. Astronomy, botany, chemistry, natural philosophy, natural history, anatomy. Not indeed to be proficient in them; but to possess their general principles and outlines, so as that we may be able to amuse and inform ourselves further in any of them as we proceed through life and have occasion for them. Some knowledge of them is necessary for our character as well as comfort.

I suppose no man who ever lived applied the learning appropriate to a liberal education more effectively and more directly and with greater success than Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson's entire life was nothing so much as a brilliant demonstration of the applicability of the huinanities and the sciences, without false distinction between them, to the problems of a life—even the most dangerous problems—even the most difficult life. But Thomas Jefferson himself, you observe, is unable to justify except as a luxury—"a delicious luxury indeed but not to be indulged in by one who is to have a profession to follow for his subsistence"—that whole realm of higher mathematics beyond the quadratic equation and the use of logarithms—"the conic sections, curves of the higher orders .... fluxions."

Where Mr. Jefferson stammers, one may forgive ordinary mortals—even college faculties and college administrations—for being dumb. But the refusal—perhaps I should say the failure—of the liberal arts colleges to concern themselves with the application of what they teach, understandable though it may be, has had unfortunate consequences. It has tempted cynics outside the colleges and fools within to deny that there is an application. American demagogs, in politics and press, have been able to deride liberally educated men as innocents, and even—what is far worse in the vocabulary of demagogy —as idealists. Cheerful college graduates, full of beer and reunion, have been free to declare without fear of contradiction that the real end and aim of liberal education is the friendships you make and the social advantages which accrue therefrom. Precious professors have felt no embarrassment in admitting over the teacups or the cocktail glasses that what a liberal education really educates you for is not the living of life but the leisure hour at the day's end when the cultivated man may take down the volume of Pater, opened and made intelligible to him in his junior year: the inner, secret life of the mind which a man may keep to himself for his delight and sustenance even in the brassy and insistent clatter of his office, like a morsel of rock candy in the cheek.

What has happened at Dartmouth therefore is not only something new but something of considerable importance. Those responsible for the conduct of this College have declared their confidence that there is in truth and in fact an application to life of the liberal arts curriculum. They have said in effect—and if the words I put in their mouths are not words they like the taste of they have time reserved to say so—they have said in effect that the purpose of a liberal education is neither to furnish a room in an ivory tower nor to qualify a man for membership in a bankers' country club but to prepare him to live his life. They have said, further, that since the purpose of a liberal education is to prepare a man to live his life, it should be possible—l think they have said it must be possible—to apply the results and consequences of a liberal education to the various situations which life, from time to time, presents.

This labor of application is not, however,—at least in their opinion—simple or easy or automatic. It does not accomplish itself in a man as the natural result of entering a polling booth and looking at a ballot. It involves skill—a very high order of skill;—and experience—a very difficult and often costly kind of experience. For—this is the point I would like to make this evening— to apply the results and consequences of education to the various situations which life presents, it is necessary,first, to recognize and correctly to definethose situations in terms with which the intelligence can deal—in terms, that is to say,of the exercise of judgment and the exertion of choice. It is necessary, thereafter, tobring to bear upon the consideration ofthese situations, thus defined, the knowledge relevant to them and the disciplineof mind by which that knowledge canbe made useful and effective.

That line, of reasoning leads, of course, to this room and your presence in it. It leads also, though not so ineluctably, to mine. Or, rather, it points the way to the answer to the question I have been asked to discuss with you. A situation in the external world, seen in terms of the exercise of judgment and the exertion of choice, is a situation seen in terms of the issue it presents. And, conversely, an issue, in the sense in which the word is used in this course, is the nub, the heart, the crux of a situation in the external world which demands the exercise of judgement and the application of choice. Theoretically, it is any such situation, whether private to a single man or universal to all. Actually, given the time at your disposal, and the extremely public nature of your discussions, it is limited to those issues of general concern and more than personal urgency which men may be expected to feel and therefore to debate in common.

I should like to return later to the characteristics of a Great Issue thus defined. First, however, there is a question common to the discussion of all issues, great or small, public or private—the question of recognition, of definition. To my mind, the most difficult labor you will undertake in this course will be this labor of definition. To my mind also your year will be well spent and far more than well spent if you succeed in agreeing among yourselves on the real nature of the great public issues of your time, regardless of the conclusions you may reach about them.

One of your two text books of the year offers a recent example of the definition of an issue which may be illuminating. The New York Herald Tribune, excellent newspaper, has conducted for years past a public forum of great distinction and value, one of the most important laboratories of opinion in the country. Each year's forum is assigned an overall subject in an effort to approach someone of the most important public issues of the period. The subject this year, according to the Herald Tribune for September 28 is to be "Modern Man: Slave or Sovereign"—a title which most of us, I think, would accept as having meat and meaning whatever we may think of its slogan-like form. The first session of the Forum is to attack this question, according to the same issue of the paper, "through inquiry into the factors that today promote or limit the freedom of the individual," its subject being "America's Problems of Liberty." Again, most of us would agree that America's problems of liberty are properly included in any examination of the question whether modern men are sovereigns or slaves and that the issue, thus narrowed, has become more real and more precise. When this narrower subject is further broken down into specific heads for actual discussion, however, the sense of meaning, the sense of significance suddenly and astonishingly disappears. Speakers before this session of the Forum are to discuss, we are told, the relation of "the problem of liberty to our own territories by presenting the case for Alaskan and Hawaiian statehood" and the relation of "the problem of civil rights" to the voteless citizens of the District of Columbia. In addition there will be a presentation of the case for Universal Military Training, a report by the American lady who acts as tutor to the Crown Prince of Japan and a closing address by the Secretary of Defense.

What has happened, quite obviously, is that the great central issue, boldly blocked out in the beginning, has been lost in the analytical process of breaking it down for discussion and debate. The reasons, I have no doubt, are good reasons: a public forum of this character must be one of the most difficult things to arrange on earth or off it. But the fact nevertheless remains. And it is an important fact. America's Problem of Liberty is a critical problem. In my opinion it is a part of the most critical, the most urgent and the most dangerous problem of our time. But America's Problem of Liberty is not the problem of statehood for Alaska or Hawaii, or the problem of the vote "'in the District of Columbia, or even the problem of compulsory military service. America's problem of liberty, I venture to suggest to you, gentlemen, is the basic and ,fundamental problem of the freedom of, mind and the freedom of conscience and the freedom of expression in the United States. It is a problem posed to you and to all other Americans at present by the current efforts of a small but ignorant and bigoted minority in the Congress of the United States to subject the opinions of the American people to inquisition and control and thus to subvert the constitutional right of the American people to think as they please and to. say what they think. But this ignorant and bigoted minority would be powerless if it did not have behind it the active support of powerful, organized groups in American life and if it did not have around it the apathy, and even the half sympathetic tolerance, of a considerable part of the American people. The issue of freedom of mind and conscience, in other words, is a real and present issue. It is an issue which cuts deep, not only into the body of the people but into the minds and souls of individual men and women who, because they hate and fear the particular opinions which are now being silenced, refuse to see that the power to silence any opinion is the power to silence all. It is the issue posed by those who say on the one side: "Why should we give our enemies freedom to end our freedom?" and by those who reply, on the other: "Why should we end our freedom because it is attacked by our enemies?" It is an issue, one would think, which deserves discussion in any approach to "America's Problems of Liberty."

I use this example, not by way of criticism of the Herald Tribune Forum to which the country owes a great deal, but by way of illustration of the particular problem before us. The managers of the Forum, who have been examples of excellence so often, will not mind, for once, being examples of something else. What is wrong with their analysis of the isuue of liberty in America is the fact that it lacks the two things essential to the correct definition of any issue. It lacks historical perspective and it lacks moral perspective. It also lacks, or so it seems to me, the exercise of the primary faculty of observation, but that, perhaps, is a matter of judgment. Of the other two—and I should like to begin with historical perspective—there can be no doubt.

The issue of liberty in America has been framed, as all of you are aware, by a long and continued historical conflict. The central element in that conflict, going back to Plymouth and before Plymouth to William Brewster's responsibility for the publication in Leyden of the Perth Assembly, was the struggle for freedom of mind and freedom of conscience. That struggle has taken many forms but the most persistent has been precisely the form in which it now presents itself—an effort by the perennial enemies of liberty of mind and liberty of conscience to use a danger, abroad, real or imaginary, as a justification for the suppression of unpopular opinions at home. Samuel Eliott Morison is writing of the United States of 1798, not the United States of 1947, when he describes the nation as "actually if not formally at war with a country that used propaganda to prepare the ground for invasion," and speaks of the Alien and Sedition Acts of that year as aimed against "an indigenous radical movement which had many points of sympathy with the French Revolution and which for other reasons the dominant party wished to discredit and crush."

The close parallel between that time and this is made even more apparent by the Jefferson letter from which I have already read. Writing while the Alien and Sedition Acts were still in force, Jefferson puts the inwards of the issue in these terms: "I am among those," he says, "who think well of the human character generally." (Wonderful to be able to say that.) "I consider man as formed for society, and endowed by nature with those dispositions which fit him for society. I believe also, with Condorcet.... that his mind is perfectible to a degree of which we cannot as yet form any conception .... I join you therefore in branding as cowardly the idea that the human mind is incapable of further advances. This is precisely the doctrine which the present despots of the earth are inculcating, and their friends here re-echoing; and applying especially to religion and politics We are to look backwards .... and not forward But thank heaven the American mind is already too much opened to listen to these impostures; and while the art of printing is left to us, science can never be retrograde; what is once acquired of real knowledge can never be lost. To preserve the freedom of the human mind, then, and freedom of the press, every spirit should be ready to devote itself to martyrdom; for as long as we may think as we will, and speak as we think the condition of man will proceed in improvement." To which the man of middle age, author in his youth of the Declaration of Independence, adds these three sentences for his younger correspondent's particular attention; "The generation which is going off the stage," wrote Jefferson, "has deserved well of mankind for the struggles it has made, and for having arrested that course of despotism which had overwhelmed the world for thousands and thousands of years. If there seems to be danger that the ground they have gained will be lost again, that danger comes from the generation your contemporary. But that the enthusiasm which characterizes youth should lift its parricide hands against freedom and science would be such a monstrous phenomenon as I cannot place among possible things in this age and this country."

Mr. Jefferson's voice, I think you will agree, sounds almost as close to this present time of ours as the voice of David Lilienthal replying to a certain Senator who will be remembered in the history of his country only because he provoked that famous outburst. And there are other voices of Jefferson's time but on the other side of the chasm of liberty, which sound not much farther off. John Adams, refusing passports to a delegation from the Institute of France who wished to visit the United States "with a view to improving and extending the sciences," speaks in the tone and almost in the words of those frightened and suspicious men in the present Congress who fear all scientists and all scholars because they speak to each other in the language of civilization across the frontiers of politics and party. "We have too many French philosophers already," said Mr. Adams, "and I really begin to think, or rather to suspect, that learned academies .... have disorganized the world and are incompatible with social order."

It is hardly necessary, however, to argue to students in Dartmouth College that a correct definition of the issues facing mankind requires the perspective of human history. What may require argument is the contention that the recognition of those issues requires a moral perspective as well. And yet it seems to me obvious even in the example under discussion. Every difference of opinion presents an issue of sorts. Statehood for Alaska is undoubtedly an issue in Alaska. Given the persuasive powers of Governor Gruening it may turn out to be an issue in the Herald Tribune Forum as well. Votes for the citizens of the District of Columbia is already an issue in the Washington Post and may well become, under the prodding of that brilliantly edited newspaper, an issue in Congress. But neither the one nor the other is the American issue of liberty nor an illustrative expression of that issue. Not only has the American issue of liberty been otherwise shaped by the history of the struggle for liberty in the United States. It also involves moral values, moral principles, which are not put in play by debate on either topic. The American issue of liberty is the issue framed by Jefferson and before Jefferson by the forces which produced him. It is an issue between those on the one hand who believe literally and actually and altogether in the right of men to "think as we will and speak as we think," and those on the other who, whatever their protestations, believe only in the right of men to think as they think and to speak as they speak. It is an issue, in other words, of principle in the most precise sense of that shop-worn word. And so, in my opinion, are all great issues always.

On this point, as I have said, I do not expect your entire agreement. There are always, in any company, practical and realistic men who prefer to live by what the lawyers call the case system, founding their actions on the precedents of earlier actions like the sensible creatures of the coral who build their houses on their fathers' heads instead of suspending their habitations from the eternal rafters of principle in perfect and symmetrical patterns of belief like the philosophic spider. President Conant of Harvard tells me, however, that the scientists of the OSRD used to comfort themselves during the dark days of the atomic experiment by reminding each other of the turtle who makes progress only when his neck is out. After what followed I have reminded myself of that often. In my opinion, for whatever my opinion may be worth, it is impossible to estimate correctly the meaning of events in the external world, and particularly in the political world, without relating those events to the ends and aims of human life —which means, judging those events by values having human significance—which means, perceiving those events in a moral and humane perspective.

Some of you will object that this highsounding and noble sentiment leaves no place for the so-called practical politician who does very well among the issues of the political world with a minimum of moral values. The answer to that is easy. The answer is, Does he? Has he? Is he handling the world food crisis well at this moment? Has he really handled any great crisis well at any time in history? Is the whole record of democratic history not a record of the failure of the practical politician and his replacement by the man of moral conviction and moral courage whenever the going gets tough?

There is another objection, however, which cannot be met by asking rhetorical questions. That is the objection that a man who demands an understanding of the end and aims of life as a basis for action is demanding a great deal. And to that I have no reply but to say that he is indeed demanding a great deal; but that a great deal, and even more than a great deal is required of us.

I realize, of course, that I am speaking of something which is not ordinarily discussed in terms of education and educational institutions. I realize that education is commonly thought of, not as defining the ends and aims of life but as being itself defined by the ends and aims which the contemporary society accepts. Thus, in the Middle Ages, when all mankind was committed to a common journey through the shadows of this transitory world to the realities of the next, education for life was, as a matter of course, education for that other life to which every soul aspired. And in the world of Greece, when the bright and sensuous reality was here on the yellow earth and the wine-dark sea, and life was the art of living, and the end of living was to be most a man, education for life was education for human wisdom.

Ours, however, is neither the age of heaven nor the age of earth but a time between, and the philosophers are either disregarded or silent, and the sense of end, the sense of aim, is lacking, not only in our own country but throughout the world, and its lack, its absence is the greatest danger which menaces our generation. For its lack underlies the sense of the loss of control of our own destiny which is the characteristic sickness of modern men. And from that sickness springs the world neurosis of fear and hatred which seems about to drive us shrieking into insane war. It is not because men differ on a fundamental issue which can never be resolved except by violence and war that they hate and fear each other: it is because they hate and fear each other that the issue on which they are divided seems to them a fundamental issue which only war can solve.

On the surface, and in the lurid light of contemporary passions, it may well seem that the human society of our time is hopelessly and fatally divided between nations and among nations and within nations on an issue from which there is no escape by reason or intelligence. The fanatics of both extremes have, indeed, made it an article of faith, the denial of which is tantamount to treason in either camp, that the division is absolute and final and can never be expunged except by bloodshed. Actually, however, anyone who will look beneath the emotional words—anyone who will disregard the childish prophecies of inevitable war between the economic classes or the unchristian principle of the inevitable war between the Christian Church and its adversaries—anyone who will refuse to be overwhelmed by the shadowy rhetoric of historical necessity and theological compulsion and dialectical fate—will find that the actual difference is a difference not of ends but means—that the ends are not regarded—that it is, indeed, precisely because the ends are not regarded that the means are swollen to the things they are.

The truth is that the ends, in any meaningful sense of the word end, are not only not in conflict in our day they have not even been considered at either pole. If the entire Communist program were carried out to the last detail so as to assure an entirely adequate supply of goods and services to every Communist subject without bureaucratic or party inequality of any kind it would still remain for the Communist state or its governors to decide what the good life is for men thus freed from economic risk and hazard. If the stated ideals of capitalism were realized to the point of providing all capitalist citizens with an equal economic opportunity to acquire the products of industry and agriculture in a society safe from the scourge of recurrent unemployment and depression, it would still be necessary to determine what, beyond the accumulation of food and clothes and radios and cars and material conveniences, makes up a positive, human and creative life worthy of free men.

These questions of the real end of life as life, of the real destiny of men as men rather than as producers or consumers of goods, have not been answered or even seriously examined by the societies of any industrialized country. And for a reason which derives directly from their industrial character. These modern societies are children of the industrial revolution and the industrial revolution was a revolution of tools, a revolution of instruments, in brief, a revolution of means. Its effect upon the traffic in ideas in every society it touched was to divert men's minds from the ends of life to the means of life. Human beings in industrialized nations no longer directed their attention, as they had in the Middle Ages and in the Mediterranean World, to the ends and purposes of their existence. They considered instead with passionate intentness how the instruments of life, the means of life might be improved. The consequence was the appearance of political systems dictated by the means, civilizations shaped by the means, philosophies obsessed by the means. And the result of the appearance of institutions conceived in these terms was and is that they conflicted with each other in these terms also. The dictation of political structures by economics, which is the science of political means, meant that political systems were compared with each other in terms of means rather than in terms of human value by which Plato would have judged them. The dictation of the form of cities and the manners of men by mechanical inventiveness meant that civilizations were balanced against each other in the scales; not of beauty and leisure, but of novelty and convenience. The stories of American soldiers who preferred Germany to France because the bathrooms were shinier and the express highways wider may not be true in fact but they are true in truth—and not for the Americans alone.

In order to see the gathering issue of our time for what it is instead of what it is not, and in order to face it as men instead of as neurotics, we must somehow, contrive to feel ourselves to be men again and to see the world in the perspective of a human purpose. Without a sense of aim it is impossible to see the differences of means for what they are and without a sense of purpose it is not easy to avoid the vertiginous feeling, which the Marxists have made the foundation of their philosophy, that the real control of life has passed from the minds of men to the "things," to the "laws," to something called "history." As long as this feeling of impotence persists in human societies men will continue, like children in the helpless dark, to respond to every challenge with hysteria and hate. And as long as men continue to regard each other with hysteria and hate, the technological devices which bind them together will bind them together like serpents in a sack not for life but death.

All this sounds, I am aware, much more emphatic and earnest than academic lectures are expected to be. But in a sense this is not an academic course. For one thing, you are dealing with problems not of theoretical but of immediate and urgent importance. For another, it is you, it is your generation, which will determine whether or not those problems will be resolved.

It comes with bad grace, I am well aware, from a member of my generation to say to members of yours that unless you can reduce the vast, confused and yammering incoherence of our time to its essential elements, its fundamental issue, your lives and all you hope to make of them will come to nothing. We have given you as little guidance and as poor example as ever one generation left to another. We have contributed—we who are now aliveneither understanding nor intelligence nor statesmanship but only passionate words and pettiness of spirit to the evil situation we ourselves inherited. Nevertheless, and however awkwardly it may come from us to you, we have nothing else that we can truly say but this. Until men know what the choice before them really is they cannot choose. Until they recognize the human issue in human terms they cannot act as men in peace and reason to resolve it. That task is yours.

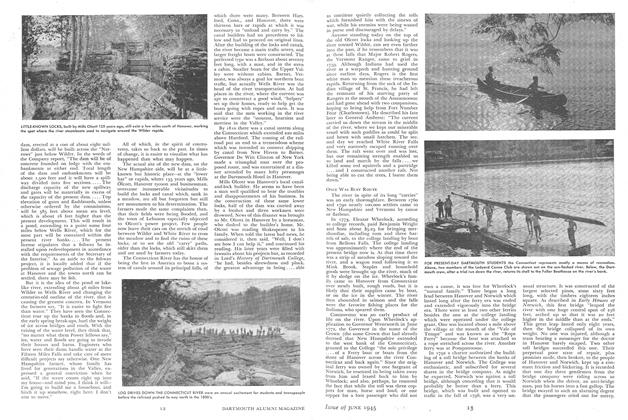

DELIVERS KEYNOTE LECTURE TO SENIORS: Archibald MacLeish, former Assistant Secretary of State, whose October 9 talk set the theme for study and discussion to follow in the new Great Issues Course.

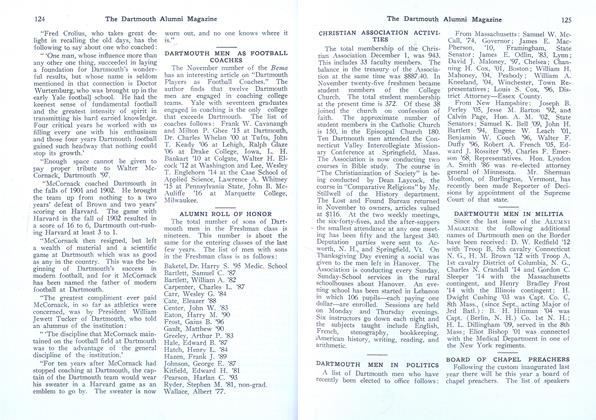

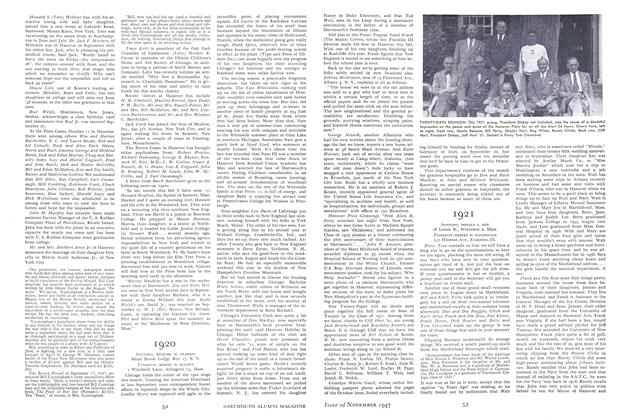

SENIORS IN THE GREAT ISSUES COURSE shown (left) waiting tor the first class to begin and (right) listening to President Dickey in 105 Dartmouth Hall.

ARE THERE ENOUGH SEATS? Getting over 600 seniors comfortably settled in 105 Dartmouth for the Great Issues Course was the problem in hand when this picture was taken of (left to right) Prof. Arthur M. Wilson, associate director; President Dickey, director, and Thomas W. Braden '40, executive secretary.

THE OVERFLOW OF STUDENTS unable to squeeze into Webster Hall for the exercises opening Dartmouth's 179th year hear President Dickey's convocation address by means of loud speakers outdoors.

FORMER ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF STATE

Mr. MacLeish's lecture, delivered at Dartmouth on October 9, was scheduled as a sort of keynote address for the entire Great Issues Course. The MAGAZINE is privileged to be able to print it in full.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

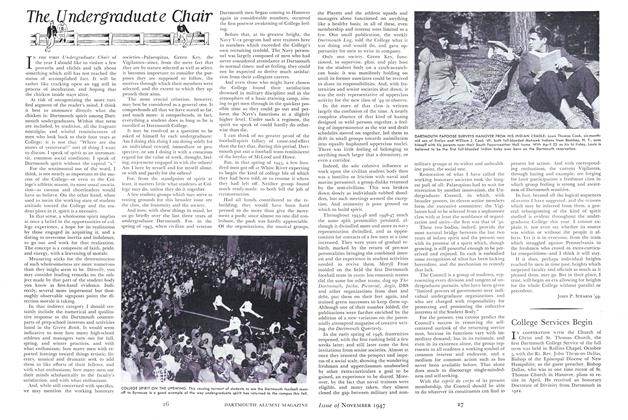

ArticleThe, Undergraduate Chair

November 1947 By JOHN P. STEARNS '49. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

November 1947 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

November 1947 By DONALD G. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD -

Article

ArticleCENTER CAMPAIGN OPENS

November 1947 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1914

November 1947 By DR. WALLACE H. DRAKE, RUFUS L. SISSON JR.