IN THE FIRST Undergraduate Chair of the year I should like to violate a few proverbs and cliches and talk about something which still has not reached the status of accomplished fact. It will be rather like cracking open an egg still in process of incubation, and hoping that the chicken inside stays alive.

At risk of antagonizing the more rarified segment of the reader's mind, I think it best to announce directly what the chicken is: Dartmouth spirit among Dartmouth undergraduates. Within that term are included, by tradition, all the fragrant nostalgias and wistful reminiscences of men who look back to their four years at College; it is not that "Where are the snows of yesteryear?" sort of thing I want to discuss. I speak of spirit as an unromantic, common social condition; I speak of Dartmouth spirit without the capital "s."

For the sentimental use of the word, I think, is not nearly as important to the success of the College—or even to the College's athletic season, its most usual association—as custom and cheerleaders would have us believe. On the other hand, when used to mean the working state of student attitude toward the College and the student place in it, spirit is a necessity.

In that sense, a wholesome spirit implies at once a belief in the opportunities of college experience, a hope for its realization by those engaged in acquiring it, and a daring to overcome inertia and indolence, to go out and work for that realization. The concept is a composite of faith, pride, and energy, with a leavening of morale.

Measuring sticks for the determination of such wholesomeness are more numerous than they might seem to be. Directly, you may consider leading remarks on the subject made by that part of the student body you know as first-hand evidence. Indirectly, several more impersonal but thoroughly observable signposts point the direction morale is taking.

In that indirect category I should certainly include the numerical and qualitative response to the Dartmouth counterparts of prep-school interests and activities listed in the Green Book. It would seem indicative to note how many high-school athletes and managers turn out for fall, spring, and winter practices, and with what enthusiasm; how many men with reported leanings toward things artistic, literary, musical and dramatic seek to add them to like efforts of their fellows, and with what enthusiasm; how many men use their minds scholastically to the faculty's satisfaction, and with what enthusiasm.

And, while still concerned with specifics, we may mention the working honorary societies—Palaeopitus, Green Key, the Vigilantes—since, from the mere fact that they are by nature selected as well as select, it becomes important to consider the purposes they are supposed to follow, the motives through which their members were selected, and the extent to which they approach their aims.

The most crucial criterion, however, may best be considered as a general one. It comprehends all that we have stated so far, and much more: it comprehends, in fact, everything a student does as long as he is enrolled at Dartmouth College.

It may be resolved as a question to be asked of himself by each undergraduate: Am I doing this thing I am doing solely for an individual reward, immediate or prospective, or am I doing it with a conscious regard for the value of work, thought, feeling, enjoyment engaged in with the others? Am I here by myself and for myself alone, or with and partly for the others?

For, from the standpoint of spirit at least, it matters little what students at College may do, unless they do it together.

A few student groups which may serve as testing grounds for this broader issue are the class, the fraternity and the society.

And now, with these things in mind, let us go briefly over the last three years of undergraduate Dartmouth. For, in the spring of 1945, when civilian and veteran Dartmouth men began coming to Hanover again in considerable numbers, occurred the first postwar awakening of College feeling.

Before that, at its greatest height, the Navy V-12 program had sent trainees here in numbers which exceeded the College's own recruiting tenfold. The Navy personnel was largely composed of men who had never considered attendance at Dartmouth in normal times; and so feeling, they could not be expected to derive much satisfaction from their collegiate careers.

And even those who might have chosen the College found their satisfaction drowned in military discipline and in the atmosphere of a basic training camp, aiming to get men through in the quickest possible time so they could go out and perform the Navy's functions at a slightly higher level. Under such a regimen, the spirit we speak of could hardly do otherwise than die.

I can think of no greater proof of the football-spirit fallacy of cause-and-effect than the fact that, during this period, Dartmouth put out a football team reminiscent of the heyday of McLeod and Howe.

But, in that spring of 1945, a few hundred men got off at White River expecting to begin the kind of college life of which they had been told, or to resume it where they had left off. Neither group found much ready-made; to both fell the job of reconstruction.

Had all hands contributed to the rebuilding, they would have been hard pressed to do more than give the movement a push; since almost no one did contribute, the push was hardly appreciable. Of the organizations, the musical groups, the Players and the athletic squads and managers alone functioned on anything like a healthy basis; in all of these, even membership and interest were limited to a few. One small publication, the weekly Dartmouth Log, told the College what it was doing and would do, and gave opportunity for men to write in company.

Only one society, Green Key, functioned, to supervise, plan, and play host for the student body on a catch-as-catch-can basis; it was manifestly holding on until its former associates could be revived to share its responsibilities. And, with fraternities and senior societies shut down, it was the only representative of upperclass activity for the new class of '49 to observe.

In the story of that class is written largely the confusion of the time. A nearly complete absence of that kind of hazing designed to weld persons together, a feeling of impermanence as the war and draft schedules moved on together, led them to drift in small groups towards assimilation into equally haphazard upperclass nuclei. There was little feeling of belonging to anything much larger that a dormitory, or even a corridor.

Indeed, the sole cohesive influence at work upon the civilian student body then was a hostility or friction with naval and marine personnel, a group dislike returned by the non-civilians. This was broken down slowly as individuals rubbed shoulders, but such meetings seemed the exception. And animosity is poor ground on which to build spirit.

Throughout 1945-46 and 1946-47 much the same split personality persisted, although it dwindled more and more as navy representation dwindled, and as opportunities for contacts of a few men at a time increased. They were years of gradual rebirth, marked by the return of pre-war personalities bringing the combined interest and the experience in student activities needed to revive them. Meryll Frost molded on the field the first Dartmouth football team in years: less romantic names did the same for other teams, dug up TheDartmouth, Jacko, Pictorial, Aegis, DBS and other organizations from dust and debt, put them on their feet again, and trained green successors to keep them up. Although one of their number folded, the publications were further enriched by the addition of a new variation on the perennially attempted magazine of creative writing, the Dartmouth Quarterly.

In the early spring of 1946, fraternities reopened, with the first rushing held a few weeks later; and still later came the first invitations from senior societies. Almost at once they restored the prospect and impetus of a social scale, showing the wandering freshman and upperclassman unabsorbed by other extra-curriculars a goal to be gained, an experience to be shared. Moreover, by the fact that naval trainees were eligible, and many taken, they almost closed the gap between military and nonmilitary groups at its widest and unhealthiest point, the social one.

Restoration of what I have called the working honorary societies took the longest pull of all: Palaeopitus had to wait for recreation by another innovation, the Undergraduate Council, in which, with broader powers, its eleven senior members form the executive committee; the Vigilantes had to be selected from a sophomore class with at least the semblance of organization and unity—the first was that of '50.

These two bodies, indeed, provide the most natural bridge between the last two years of infant spirit and the present one with its promise of a spirit which, though growing, is still powerful enough to be perceived and enjoyed. In each is embodied some recognition of what has been lacking heretofore, and the mechanism to remedy that lack.

The Council is a group of students, representing every division and tangent of undergraduate pursuits, who have been given "limited powers of government over individual undergraduate organizations and who are charged with responsibility for protecting and promoting the collective interests of the Student Body."

For the present, you cannot predict the Council's success in removing the selfcentered outlook of the returning service man, because its functions vary with immediate demand; but in its rationale, and even in its existence alone, the group represents to all students a working symbol of common interest and endeavor, and a medium for common action such as has never been available before. That alone does much to discourage single-mindedness and self-seeking.

With the esprit de corps of its present membership, the Council should be able to do whatever its constituents can find to present for action. And with corresponding enthusiasm, the current Vigilantes, through hazing and example, are forging for later participation a freshman class in which group feeling is strong and awareness of Dartmouth sensitive.

In fact, beyond all the logical sequences of events I have suggested, and the reasons which may be inferred from them, a general reburgeoning of the kind of spirit studied is evident throughout the undergraduate College this year. I cannot explain it, nor even say whether its source was within or without the people it affects. Yet it is in everyone, from the team which struggled against Pennsylvania to the freshmen who crowd to extra-curricular competitions—and I think it will stay.

If it does, perhaps individual heights reached by men in time past, heights which surprised faculty and officials as much as it pleased them, may go. But in their place, I trust, will begin an era allowing for heights for the whole College without parallel or precedent.

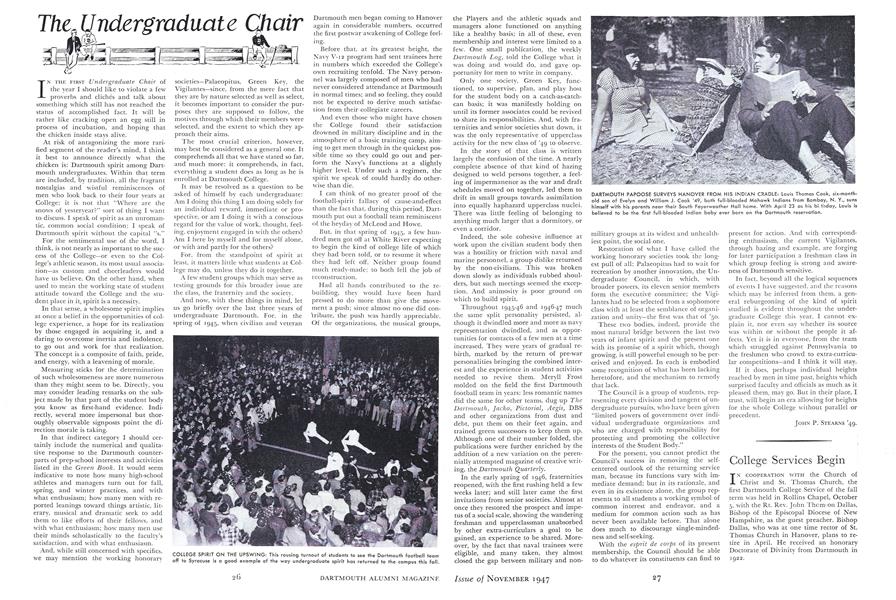

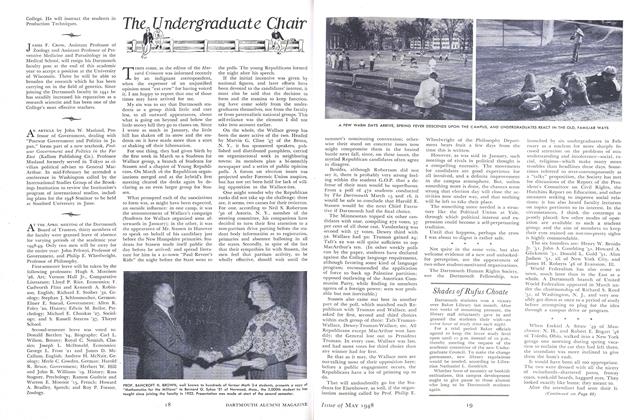

COLLEGE SPIRIT ON THE UPSWING: This rousing turnout of students to see the Dartmouth football team off to Syracuse is a good example of the way undergraduate spirit has returned to the campus this fall.

DARTMOUTH PAPOOSE SURVEYS HANOVER FROM HIS INDIAN CRADLE: Louis Thomas Cook, six-month-old son of Evelyn and William J. Cook '49, both full-blooded Mohawk Indians from Bombay, N. Y., suns himself with his parents near their South Fayerweather Hall home. With April 23 as his birthday, Louis is believed to be the first full-blooded Indian baby ever born on the Dartmouth reservation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWHAT IS A GREAT ISSUE ?

November 1947 By ARCHIBALD MACLEISH, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

November 1947 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

November 1947 By DONALD G. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD -

Article

ArticleCENTER CAMPAIGN OPENS

November 1947 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1914

November 1947 By DR. WALLACE H. DRAKE, RUFUS L. SISSON JR.

JOHN P. STEARNS '49.

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH 52—HOLY CROSS 0

DECEMBER, 1907 -

Article

ArticleBOSTON UNIVERSITY CLUB PLANS LECTURE SERIES

FEBRUARY, 1927 -

Article

ArticleSuggested Form to Endow Alumni Fund Gift

December 1953 -

Article

ArticleM.D. Convocation

OCTOBER 1970 -

Article

ArticleSexual Rules

NOVEMBER 1992 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Publications

AUGUST 1929 By James P. Richardson