THE fraternity men were the first to come back. They opened up the houses, painted, hosed, and vacuumed, put mattresses out on sunny lawns to air, and between work times sat along the row, doing nothing in particular.

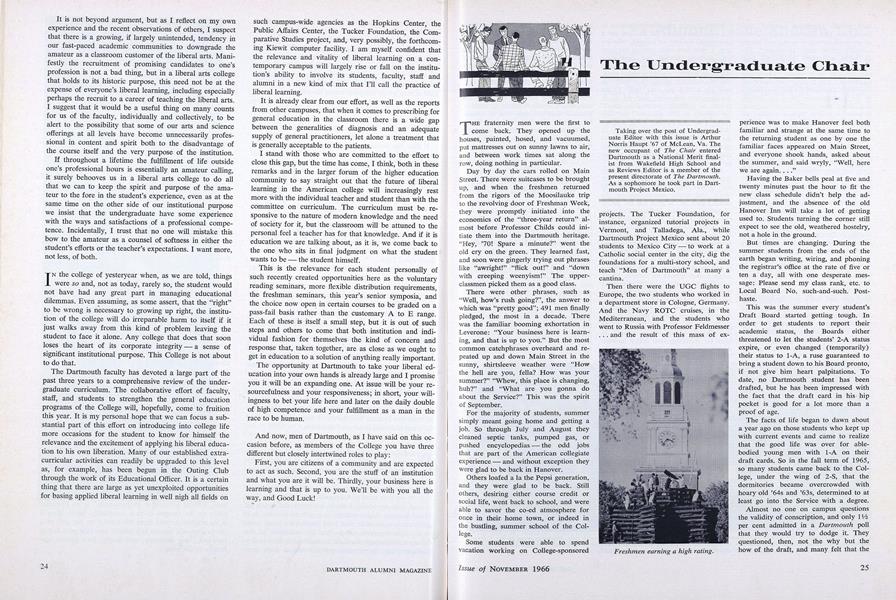

Day by day the cars rolled on Main Street. There were suitcases to be brought up, and when the freshmen returned from the rigors of the Moosilauke trip to the revolving door of Freshman Week, they were promptly initiated into the economics of the "three-year return" almost before Professor Childs could initiate them into the Dartmouth heritage. "Hey, '70! Spare a minute?" went the old cry on the green. They learned fast, and soon were gingerly trying out phrases like "awright!" "flick out!" and "down with creeping weenyism!" The upperclassmen picked them as a good class.

There were other phrases, such as "Well, how's rush going?", the answer to which was "pretty good"; 491 men finally pledged, the most in a decade. There was the familiar booming exhortation in Leverone: "Your business here is learning, and that is up to you." But the most common catchphrases overheard and repeated up and down Main Street in the sunny, shirtsleeve weather were "How the hell are you, fella? How was your summer?" "Whew, this place is changing, huh?" and "What are you gonna do about the Service?" This was the spirit of September.

For the majority of students, summer simply meant going home and getting a job. So through July and August they cleaned septic tanks, pumped gas, or pushed encyclopedias — the odd jobs that are part of the American collegiate experience - and without exception they were glad to be back in Hanover.

Others loafed a la the Pepsi generation, and they were glad to be back. Still others, desiring either course credit or social life, went back to school, and were able to savor the co-ed atmosphere for once in their home town, or indeed in the bustling, summer school of the College.

Some students were able to spend vacation working on College-sponsored projects. The Tucker Foundation, for instance, organized tutorial projects in Vermont, and Talladega, Ala., while Dartmouth Project Mexico sent about 20 students to Mexico City - to work at a Catholic social center in the city, dig the foundations for a multi-story school, and teach "Men of Dartmouth" at many a cantina.

Then there were the UGC flights to Europe, the two students who worked in a department store in Cologne, Germany. And the Navy ROTC cruises, in the Mediterranean, and the students who went to Russia with Professor Feldmesser ... and the result of this mass of experience was to make Hanover feel both familiar and strange at the same time to the returning student as one by one the familiar faces appeared on Main Street, and everyone shook hands, asked about the summer, and said wryly, "Well, here we are again. ..."

Having the Baker bells peal at five and twenty minutes past the hour to fit the new class schedule didn't help the adjustment, and the absence of the old Hanover Inn will take a lot of getting used to. Students turning the corner still expect to see the old, weathered hostelry, not a hole in the ground.

But times are changing. During the summer students from the ends of the earth began writing, wiring, and phoning the registrar's office at the rate of five or ten a day, all with one desperate message: Please send my class rank, etc. to Local Board No. such-and-such. Posthaste.

This was the summer every student's Draft Board started getting tough. In order to get students to report their academic status, the Boards either threatened to let the students' 2-A status expire, or even changed (temporarily) their status to 1-A, a ruse guaranteed to bring a student down to his Board pronto, if not give him heart palpitations. To date, no Dartmouth student has been drafted, but he has been impressed with the fact that the draft card in his hip pocket is good for a lot more than a proof of age.

The facts of life began to dawn about a year ago on those students who kept up with current events and came to realize that the good life was over for ablebodied young men with 1-A on their draft cards. So in the fall term of 1965, so many students came back to the College, under the wing of 2-S, that the dormitories became overcrowded with hoary old '64s and '63s, determined to at least go into the Service with a degree.

Almost no one on campus questions the validity of conscription, and only 1½ per cent admitted in a Dartmouth poll that they would try to dodge it. They questioned, then, not the why but the how of the draft, and many felt that the local boards sometimes misused their power and that another system - such as universal service or a national lottery - might prove more satisfactory. TheD, while editorially supporting local boards, advised national draft guidelines and national draft quotas. "As things stand now," The D said, "a student from New York City does not feel the pressure of the draft because there are enough non-college men to fill the city's quota. However a student from a middle-class suburb, where most college-age men go to school, might have to interrupt his education because of the draft."

Perhaps not yet. But while the underclassmen are not worried about getting whisked out of school, ROTC enlistment has risen substantially, and the big Selective Service exam last May brought out half the College. In general, the seniors are the ones who have to worry, as the draft obviates most activities after graduation except graduate school and the Service. This "either/or" situation does irk students, but while the percentage of Dartmouth men going to grad school has risen to 70 per cent, this is a trend of professionalism, not draft-dodging.

In this way, through letters to the registrar, in overcrowding, and altered future plans, does the war in Vietnam finally reach Hanover. Reports of it on television and radio are steadfastly ignored — it is a student tradition never to watch on the tube any show with any educational value whatsoever. The magazines and newspapers get through more easily. Finally, most students know someone who is in Vietnam.

There is some organized opposition to the war, mostly from the Students for a Democratic Society on campus, who for over a year have been passing out leaflets, showing movies, and conducting meetings and teach-ins, and occasionally picketing ROTC. On the other hand, The Dartmouth's spring term poll last year got a 70.4 per cent "yes" to the question "Do you think that the U. S. should be militarily involved in Asia?" (as opposed to 25.1 per cent "no," and 4.5 per cent "don't know"). The question "In your opinion, is the major purpose of the United States in Southeast Asia to guarantee the rights of the Vietnamese people?" brought a surprising 74 per cent "no," which is food for thought.

The argument still goes on in the dorms and fraternities. It starts out with the Geneva agreements and Ho Chi Minh, and slowly degenerates as the evening goes on, as guys run out of information and start saying, "Well, you know what I think? etc." Finally everyone starts kidding about spending 1968 in "the rice paddies" - for ultimately most students have become fatalistic about the whole thing, even many of those who don't believe in the war. There is not much gung-ho spirit, and not a single Rupert Brooke on campus, but if they have to go, they'll go. Some students have deep convictions about the Tightness of war and the Viet Cong.

But many are still undecided, and since Dartmouth students have a peculiar passion to be right all the time, the students who came out so strongly in May for Administration policy in Vietnam were the same students who last month cheered Judy Collins and Theodore Bikel in Leverone Field House when they sang two anti-Vietnam songs. This does not mean any shift in student opinion or any gullibility on the part of the College's men. The truth, rather, would seem to be that they are still undecided, and have some degree of sympathy for both the hawk and dove viewpoints. The war is a very large and complicated event; Vietnam is closer to Hanover than it seems, and no student has escaped completely from its effects. At this stage, the College's men — still 2-S, still "safe" - are just trying to be right about the war, and trying very hard.

Freshmen earning a high rating.

Coach Jim Schwedland '48 (center with name tag) accepts the Schaefer Cup for Dartmouth, top American team in the Septemberintercollegiate fishing match in Nova Scotia. At right, the Dartmouth team (l to r): Coach Schwedland, Captain Bill MacCarty '67,John Schumacher '67, Captain-elect Jack Noon '68, Bjorn Lang '68, and Dick Galardy '68

Coach Jim Schwedland '48 (center with name tag) accepts the Schaefer Cup for Dartmouth, top American team in the Septemberintercollegiate fishing match in Nova Scotia. At right, the Dartmouth team (l to r): Coach Schwedland, Captain Bill MacCarty '67,John Schumacher '67, Captain-elect Jack Noon '68, Bjorn Lang '68, and Dick Galardy '68

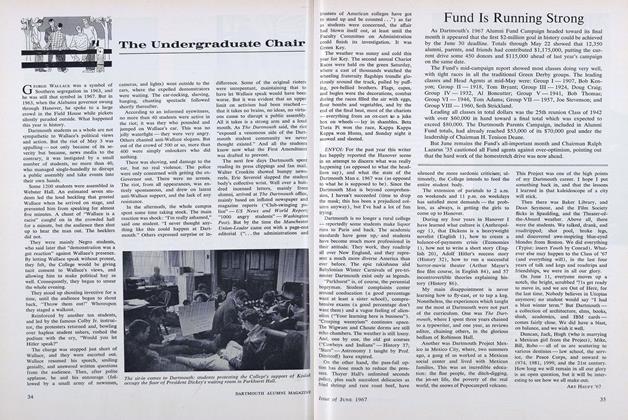

Taking over the post of Undergraduate Editor with this issue is Arthur Norris Haupt '67 of McLean, Va. The new occupant of The Chair entered Dartmouth as a National Merit finalist from Wakefield High School and as Reviews Editor is a member of the present directorate of The Dartmouth. As a sophomore he took part in Dartmouth Project Mexico.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNotes on the New Europe

November 1966 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47 -

Feature

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1905-1966 CAMPAIGN

November 1966 By Rupert C. Thompson. Jr. '28 -

Feature

FeatureTHE RACE TO BE HUMAN

November 1966 -

Feature

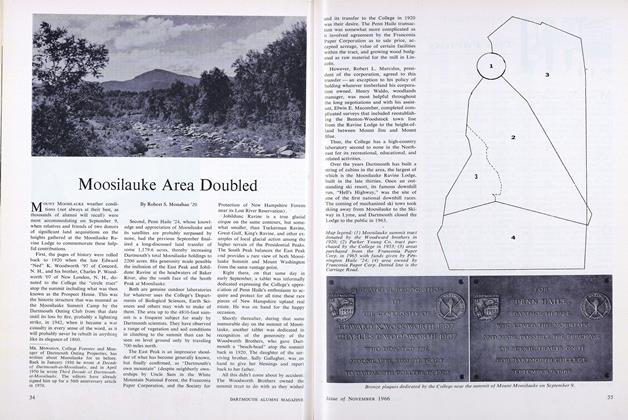

FeatureMoosilauke Area Doubled

November 1966 By Robert S. Monahan '29 -

Feature

FeatureFederal Judge

November 1966 -

Feature

FeatureNorth Country Doctor

November 1966

ART HAUPT '67

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

DECEMBER 1966 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JANUARY 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

FEBRUARY 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

APRIL 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MAY 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JUNE 1967 By ART HAUPT '67

Article

-

Article

ArticlePLAQUE OFFERED TO PREPARATORY SCHOOLS

April 1916 -

Article

ArticleThe Skier

FEBRUARY 1932 -

Article

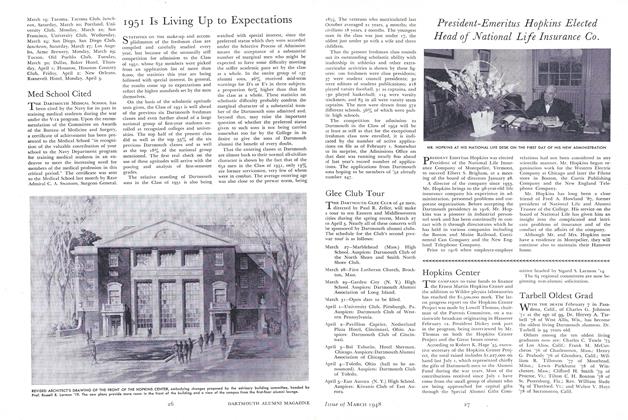

Article1951 Is Living Up to Expectations

March 1948 -

Article

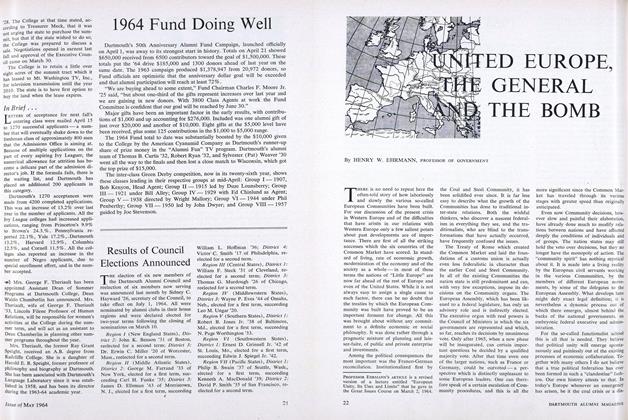

Article1964 Fund Doing Well

MAY 1964 -

Article

ArticleA HISTORY OF AMERICAN LIFE AND THOUGHT.

MARCH 1972 By ROBERT E. RIEGEL -

Article

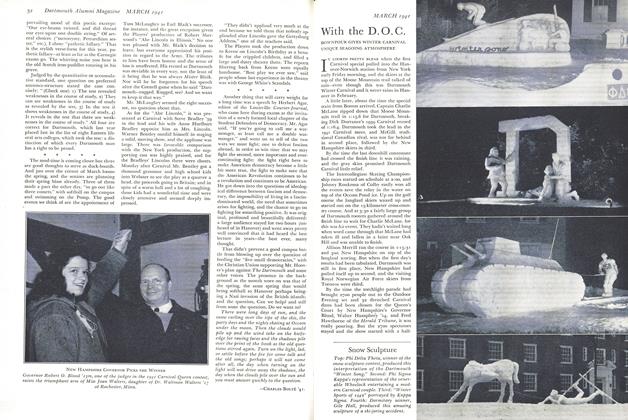

ArticleWith the D.O.C.

March 1941 By William J Mitchel Jr. '42