Intensive Courses in French and Spanish Introduced To Meet the Postwar Desire for Speaking Knowledge

MANY YEARS AGO an elderly Frenchman who, as a youth, had studied English in school, told me that on his first vacation visit to England he was equipped with a single English sentence. Upon arriving in London he could say, with a strong Gallic accent, rolling the r's gloriously, and absolutely unable to pronounce the letters h, w, or th, "Omerr vass zee grrreatest poet of Grrreece." Which sentence, he was fond of adding, his eyes twinkling as he related the incident in later days, did not help him a bit in hailing a cab or negotiating for a hotel room.

This Frenchman was a schoolboy some sixty years ago, which would give us the date of 1887. On my desk as I write is a Dartmouth Sophomore Class advanced division French examination of that same academic year, 1886-1887. It consists mostly of translation passages: two lengthy speeches from Victor Hugo's verse drama Rny Bias to be translated into English, and five English sentences to be translated into French. Two of these five sentences are: "Whatever riches he may possess, however learned he may be, whatever he may have done, it is character that makes the man," and "Astronomy is one of the sciences that do most honor to the human mind."

It would appear that a Dartmouth junior-to-be, going to Paris in that summer of 1887, was just about as well prepared to get around and make himself understood as was my old French friend in England.

Twenty years later, in 1907, when many Dartmouth freshmen and some upperclassmen were taking the famous old "French 5," they heard precious little French. To quote from the catalogue of 1906-1907, there was "a careful review of grammar. Practice in writing French. Translation of difficult French prose and poetry: Balzac, Zola, Hugo, Pailleron, Moliere." In grammar, they had it hammered into their heads that seven French nouns ending in -ou, the French equivalents for jewel, pebble, cabbage, knee, owl, toy, and louse, form their plural by adding x, not s, to the singular. In the reading book, constantly thumbing the vocabulary printed at the back, they laboriously ground out three pages of translation in preparation for each meeting of the class. They were so intent upon getting the English words that they paid little or no attention to the French words. As soon as a student had recited and been given a grade in the instructor's little brown notebook, he .could let his mind wander, or he could join in the laughter over the frequent howlers as his classmates stumbled through the translation of their ten or fifteen lines. Finally, the welcome bell would ring, announcing the end of the hour.

They were supposed to be getting "mental discipline." The professor, a former instructor in ancient Greek, used the same method that he had used in teaching Greek. The following year, 1907-1908, two fables of LaFontaine were memorized,—to be written out in French, but not to be said aloud. Naturally, with no oral drill, students had a horrible pronunciation, and never did learn to recite the poems. Nobody cared. In those days Europe and Latin America seemed to be a million miles away from Hanover.

But in the past forty years, two World Wars, radio, the cinema, and the airplane have shortened distances, and made us strikingly aware of the nearness of our foreign neighbors. The New York Times recently observed that French, Spanish, Italian, and other foreign languages have at last been taken from the museum shelf and made a part of everyday life. No longer do we make the old classical approach to the study of a language. Translation is pretty much a thing of the past. Today's Dartmouth undergraduate in "French 5" probably hears and uses more French in one hour than was heard or used in a whole semester in that course when his father or his uncle took it. And, believe it or not, it is now a common thing for students and instructors to greet each other in the foreign tongue as they pass on Main Street or on the campus paths. Courses in advanced conversation and composition are more popular at present than are the literature courses. Ex-service men, as well as boys fresh from preparatory school, clamor for something "practical," until the word has become one of the most frequently heard adjectives of the year. In conferences between students and their advisers in regard to the election of courses for the next semester, the adjective "practical" inevitably slips into the conversation.

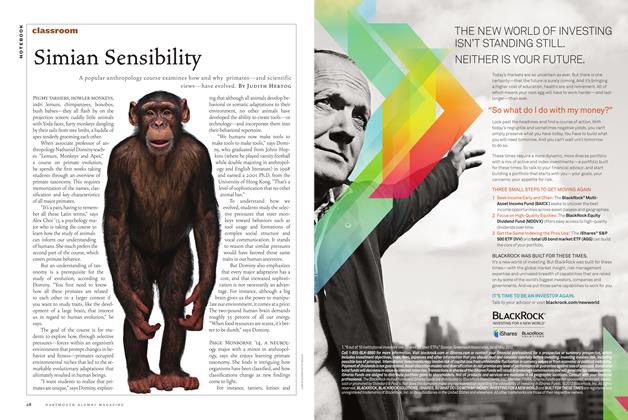

One of the Department's most interesting recent experiments was the introduction last October of two new intensive courses for beginners: French 3-4 and Spanish 3-4. Each course meets nine hours a week and aims to do two years' work in one. Only superior students who are eager to learn to speak the foreign language are admitted to these two courses. Each course is taught by natives of the foreign countries, and no English is used. In French 3-4, Professor Francois Denoeu meets the fifteen undergraduates six mornings a week for an hour. In the afternoon or evening his wife, a Frenchwoman, meets the students in three separate groups of five students each. Spanish 3-4 is conducted similarly by Senor Francisco Ugarte and his Spanish wife, who have recently come to this country from Madrid. Some afternoons or evenings the small groups meet at the Ugarte apartment for informal conversation, in pleasanter and more natural surroundings than in the formal Dartmouth Hall classroom. There are sixteen boys in Spanish 3-4.

Favorable reports come from the four teachers of these two new courses, and the boys are enthusiastic. They are really learning to speak French or Spanish, as the case may be. We think it excellent for them to become accustomed to hearing a woman's voice as well as a man's. To my query as to how he liked "Spanish 3" the first semester, a boy replied with deep conviction: "It's the finest course I've taken at Dartmouth."

This teaching is strenuous. All four teachers report that they have to be "on their toes" every minute. But they are convinced that they are getting results. As Senor Ugarte remarked to a reporter from The Dartmouth: "I have seen too many Americans who have had three or four years of Spanish in college, come to Spain and find that they didn't know enough to buy things in the shops." For supplementary work, in 52 Robinson Hall, these courses have a Recordio machine with French and Spanish records, as well as blank records for the students to record their pronunciation, which is subsequently corrected by the instructors.

One of the older members of the Department fears that we are gradually becoming a Berlitz School. But it is not likely we shall go quite as far as that. Dartmouth is still a college of liberal arts.

TWO ILLUSTRATIONS OF INTENSIVE LANGUAGE STUDY. Left, Prof. Francois Denoeu (standing) directs a group of French students using language records (shown in right foreground) in the French Club room in Robinson Hall. Professor Dunham, author of this article, is seated at the extreme left. In the picture to the right, Mrs. Francisco Ugarte, who helps her instructor husband in the new course in conversational Spanish, conducts a class in Dartmouth Hall.

PROFESSOR OF FRENCH

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

Article"Free as the Air"

March 1947 By JERRY A. DANZIG '34, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleRadio Interprets the News

March 1947 By CEDRIC FOSTER '24, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

March 1947 By JOHN H. DEVLIN, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR. -

Article

ArticlePHYSICS FOR THE FUTURE

March 1947 By PROF. ARTHUR B. MESERVEY '06. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

March 1947 By DONALD G. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD