LAST term I received two citations. One was from a New York policeman for speeding and cost me $25. The other was from a Dartmouth professor for my work in a women's studies course. "A citation in women's studies that figures," a male friend observed, implying that it was natural for me as a woman to do well in the course. Misguided, too, are those who assume that class discussions are consciousness-raising sessions. And the English professor who recently warned readers of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE about orgies of "victim studies" at the College was also misinformed.

Friends have admitted that they took women's studies with apprehension. There is a hesitation to tell parents that you're signed up for a course about women in society for fear they'll respond, "You're receiving credit for that!" or threaten, "You take a real course!" I confess that I did feel a bit guilty for taking something that was so personal and so relevant to me.

In 1978, the faculty voted overwhelmingly to support a Women's Studies Program, making Dartmouth the first previously all-male Ivy institution to provide an opportunity for certification and a modified major. The bait came too late, though, to attract me for I was well into my history major (I had vowed to major in whatever I got my first "A" in).

During my junior year, when I was enrolled in a history seminar with eight guys who were researching eight famous men, I decided to study someone who would inspire me. So for four weeks, I lived, slept, and ate like Rosa Luxemburg, a German socialist leader. But if "Bloody Rosa" was a great woman, she was exceptional and did not reflect the experience of most women of her time. In another course I studied women in Middle Eastern harems, but I learned more about men's attitudes than those of their wives and concubines. The question began to itch where were the mass of women in history?

"But women haven't done anything' came the answer. "Women haven't made history." I began to wonder, what is history then? If it is a true account about the past, then surely women - half of humanity- have stories to tell.

Last fall, I ventured into the introductory women's studies class without any intention of signing up for it. Having played soccer and squash, I'd always avoided the two o'clock slot. I found myself in a classroom composed mostly of women, a rare academic experience at Dartmouth. I was intrigued - but skeptical. I didn't want to hear women ramble and complain for three hours a week. I thought I knew the subject and should take something more challenging. (Courses with the number one don't intimidate.) But after checking the syllabus and the reading list and hearing about the requirements - a journal, two papers, and a final - my fear that it would be too easy abated. Actually, I saw too many cups of tea and two few hours of sleep before the course was through.

A scholarly approach was demanded as we explored women in history, literature, and art, and guest lecturers from a variety of disciplines added other points of view. President Kemeny, for example, spoke about women and "math anxiety." The course's three professors learned with us, making the atmosphere egalitarian and alive, and the tone remained optimistic. We studied women not as "victims" but from their own perspectives as adaptors.

I discovered why I had been unable to learn about women in history before. I had been assuming that the history I was reading was universal. It isn't. Traditional historians look at topics such as politics or wars or periods such as the Renaissance with an emphasis on dramatic change. They address questions which don't necessarily apply to women. I started to ask new questions: Was the Renaissance a rebirth for women? (Was it for most men?) I learned to consider new criteria for what is historically significant - the personal as well as the political.

Women didn't usually fight battles or make speeches, but scholars are tapping new sources - for example, journals and letters - to find out about their experiences. And they are developing new categories such as "sexuality" and "socialization" to report their findings. As Professor Mary Kelley of Dartmouth observes, "Until recently the history of women has been a blank page." It's exciting to watch the ink dry on the first pages of women's history.

That's what women's studies is all about it seeks to fill in the blanks, not build a separate empire in a corner of Carpenter Hall. Ideally, the curriculum of all departments would include contributions of women, and one function of women's studies is to generate and promote that knowledge and attitude. It implies an activism- women's studies is not just about women in society; it is also a force in the evolution of women's roles.

Certainly there are problems; there were in Women's Studies 1. Some people found the interdisciplinary approach too disjointed. Some perceived the danger of overlooking working-class and minority representatives while propounding sweeping generalizations about women. One thing we did learn was, as one classmate said, "Women want to be treated as human beings rather than relatives of human beings."

Paradoxically, women's studies addresses an already receptive audience. It teaches those who want to take a serious look at women, but it needs to teach those who want to take a serious look at women - like my brother, who has always contended that he wanted to major in women in college.

Meanwhile, I've taken a one-way-only route into the stacks at Baker Library and won't return until I've finished my thesis on Middle Eastern Muslim women. Locked in my study, I can hear the chair above me squeak, and I realize thankfully that I'm not alone. A friend is cloistered on the eighth floor, reading about Flora Tristan, a 19th-century French socialist. Most of the women writing history theses this year are writing about women. So are friends in policy studies, government, and sociology. There must be something to it, studying women.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

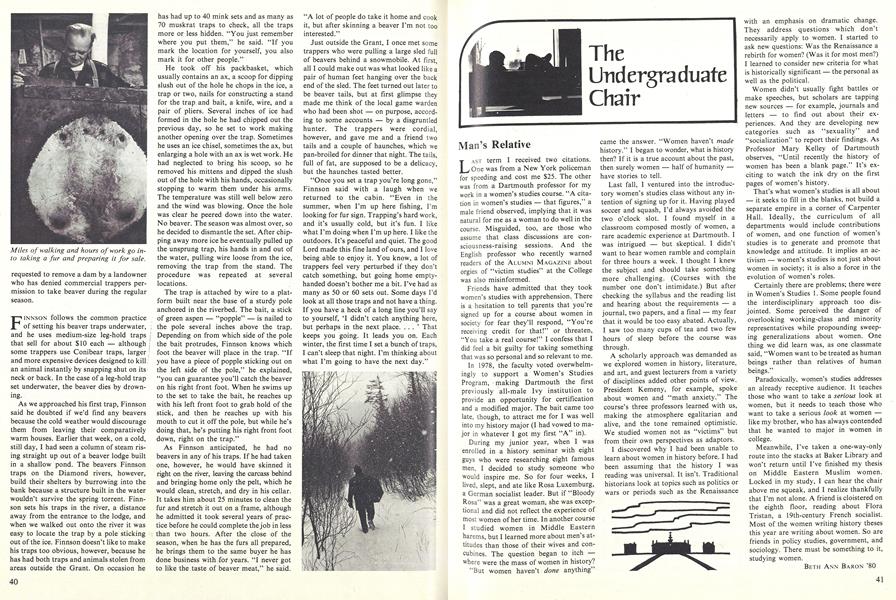

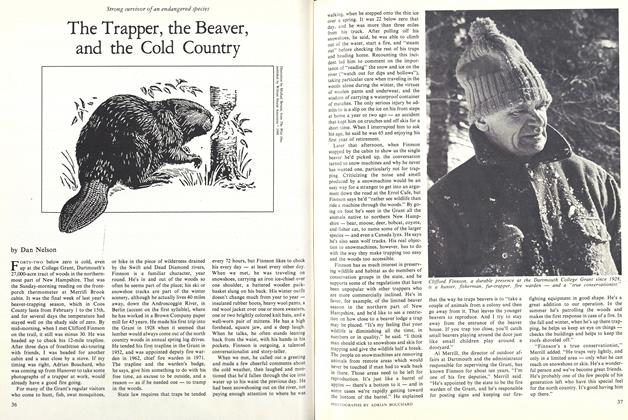

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson -

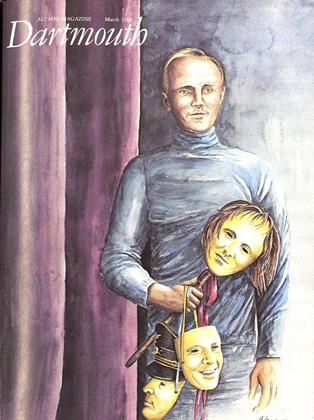

Cover Story

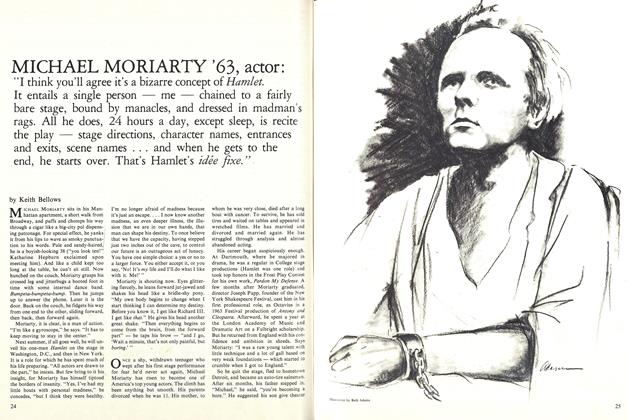

Cover StoryMICHAEL MORIARTY ’63, ACTOR

March 1980 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

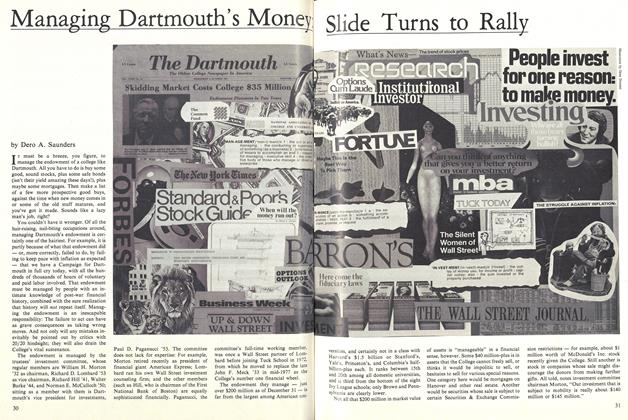

FeatureManaging Dartmouth’s Money Slide Turns to Rally

March 1980 By Dero A. Saunders -

Article

ArticleTracker of the Right Stuff

March 1980 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913

March 1980 By CARL C. FORSAITH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

March 1980 By JEFF IMMELT