THE criticism most frequently leveled against the scientist is that he considers his special field a thing apart from the history, philosophy and culture of the social milieu. This concentration of scientific energies, it is held, leads to rapid technological development but so contributes to social irresponsibility that the value of scientific findings in the area of human relations is greatly diminished. The specialist has so little faith in the scientific method as a reliable procedure that he applies it only to the restricted data of his field and flounders helplessly when expected to make independent decisions in the wider sphere of social values. Critics have claimed that this narrowness on the part of the exact scientist in his laboratory is reflected in his teaching. His courses are designed to make more narrow specialists and offer little to the student interested in general education. The non-professional student expects, beyond some knowledge of the special tools and skills of a particular science, an integrated notion of all the sciences, a vigorous analysis of the usefulness and limitations of the scientific method, and an idea of the meaning of science in relation to humanistic and social values.

In General Education in a Free Society the Harvard committee concluded that:

"From the viewpoint of general education the principal criticism to be leveled at much of present college instruction in science is that it consists of courses in special fields, directed toward training the future specialist and making few concessions to the general student. Most of the time in such courses is devoted to developing a technical vocabulary and technical skills and to a systematic presentation of the accumulated fact and theory which the science has inherited from the past. Comparatively little serious attention is given to the examination of basic concepts, the nature of scientific enterprise, the historical development of the subject, its great literature or its interrelationships with other areas of interest and activity."

How do scientists respond to these criticisms? They seem to divide into two schools of thought. The first favors the "traditional" science courses and looks upon the historical treatment, the synoptic presentation of unifying principles and reference to the impact of the body of a science on culture, as merely "talking about science" and not constituting science itself. The value of teaching science is to be found in the inherent worth of scientific fact and theory, and in the disciplinary value of vigorously applying the scientific method to the observable and measureable material at hand. Accent is placed on accurate observation, the importance of checking and re-checking the facts, the value of laboratory procedure in contributing to "intellectual honesty," etc. As investigators, members of this school feel that science as a process is degraded when its methods are applied outside the laboratory. They disavow responsibility for the impact of scientific findings on human values and feel that such matters should be handled by those specially trained for the job. This attitude is currently taking shape, for example, in the arguments of some against including funds to provide a program of scholarships and research for the social sciences in the Kilgore-Magnusson bill which proposes a government sponsored National Science Foundation.

The second school agrees that the traditional method of teaching science courses to the non-scientist needs revision and also thinks that the insular attitude of the scientist in relation to the world of affairs has worked against the best interests of society. President Conant of Harvard is an outstanding example of this group. He is a distinguished scientist who has frequently received prizes for his fundamental research in chemistry. Dr. Conant, as is well known, has freely given of his time not only to scientific aspects of atomic energy but also to legislative considerations of its control and to deliberations concerning the establishment of a National Science Foundation. Other evidence that scientists are concerned with the impact of their science on human relations can be found in the much publicized participation of many of them in the Congressional consideration of Mr. Lilienthal's appointment to the chairmanship of the Atomic Energy Commission, in the effort to keep atomic energy under civilian control, and in other aspects of the relation of this force to human society.

The attitude of these scientists toward general humanistic problems can further be found in the titles of articles currently appearing in The Scientific Monthly. This periodical is published for scientists by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. In recent issues there have been papers on such topics as: "A Physicist Looks at Morality," "Henry Adams and the Repudiation of Science," "The Parallel Roles of Physical and Social Science," "Science and the Supernatural," "Science and National Policy," "Science as the Common Ground for Relations between Nations," "Science and Incentives in Russia," "Science in UNESCO," "Science and the Pursuit of Values," etc. These are not written by men who only talk about science.-These are the Comptons and the Langmuirs who are outstanding scientists themselves and yet are aware of and participate in the general implications of their science in the world of human values.

Can the "traditional" or "ivory lab" attitude toward science and the teaching of science be reconciled with the attitude of those who are characterized as merely "talking about science?" Many believe that a workable solution can be found. For the student majoring in a science there can perhaps be little compromise with the vigorous and comprehensive drilling in the fundamentals of his particular science which is employed even in liberal arts colleges today. However, when considering what should be taught to a non-scientist, whose entire formal training in science may consist of four one-semester courses, a different approach is indicated. A "survey course" of all the sciences does not perhaps deserve serious consideration. It is bound to be superficial and would likely lead only to confusion. However, in a course stressing basic scientific principles some of the factual material presented traditionally in beginning courses might be dropped and room made for synthetic, historical and philosophical treatment. Such factual omissions would hardly be serious when under the present system a student can fulfill his science requirements without getting any physics or biology.

In relating the teaching of science to general education, the best answer might be found in selecting from all the sciences those few general and fundamental principles which underlie the various fields of scientific enterprise. Each of these principles could be dealt with intensively by lecture, discussion and experiment. The chief objective would be to illustrate the scientific method and to convey some understanding of the means by which scientific knowledge progresses historically from observation and classification, through the making and testing of hypotheses, to a final consideration of the uses of this new knowledge. This is a radical procedure in that it cuts across the boundaries of courses, departments, and even divisions of the College, but it might be found that many of the apparently irreconcilable and contradictory disciplines are actually complementary, and that the boundaries which now exist are not inherent in the real nature of the subjects.

ASST. PROF. OF ZOOLOGY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

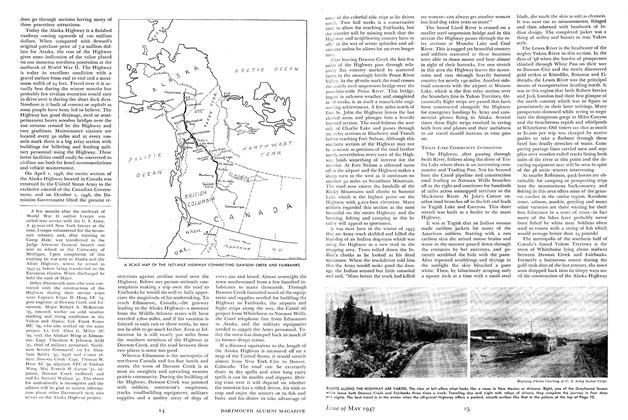

ArticleTHE ALASKA HIGHWAY

May 1947 By LAURENCE W. LOUGEE '29 -

Article

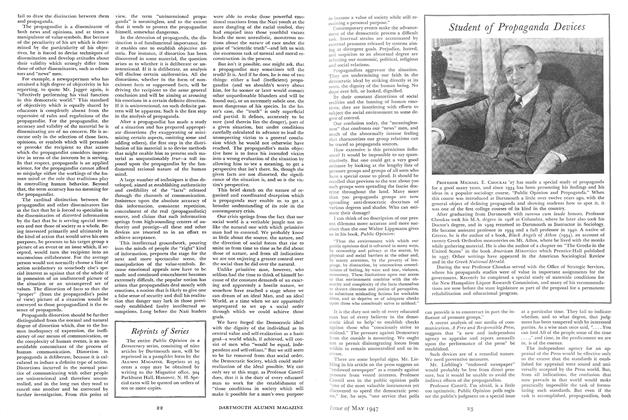

ArticlePROPAGANDA AND THE CRISIS

May 1947 By MICHAEL E. CHOUKAS '27 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleJames Parmelee Richardson

May 1947 By JOSEPH W. GANNON '99 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

May 1947 By DONALD G. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

May 1947 By JOHN H. DEVLIN, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR.