A GLANCE at the front page of any of our newspapers these days underlines the fact that scientists in increasing numbers are emerging from the academic sanctuary of their research laboratories to enter the public arena of national and international affairs. The shy, myopic scholar is leaving his bifocals and white coat behind in his traditionally cloistered ivory tower and is ready to take responsibility for action in the outside world. The current "new look" in scientists probably began with Professor Einstein's famous letter to President Roosevelt just before our entry into the war when he explained the military desirability of having the government encourage work in the field of atomic energy. Today almost everyone is aware of the extracurricular activities of a group of atom physicists who have banded themselves into the "Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists." This group, headed by Doctor Einstein, is functioning feverishly in current political matters.

Not always is the scientist treated with awe and deference in the rough and tumble of the world of affairs. As this is being written, Dr. Condon, a past president of the American Physical Society, is being slapped around by the Thomas Committee on Un-American Activities. Mme. Irene Joliot Curie, distinguished French scientist and Nobel Prize winner, has just been forcibly detained at Ellis Island. The former is accused of being indiscreet in the choice of his companions and the latter is suspect for her interest in the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee, an organization on the Attorney-General's disloyalty list. Ironically enough, Dr. Condon, lecturing here at Dartmouth about a month before the walls caved in and he was "exposed" by the Thomas Committee, told the students that the reason he left the turbulence of an established career in journalism in his youth was to retreat to the calm reflective isolation of the life of a laboratory physicist. Rough treatment of scientists when they have ventured outside their laboratories is, of course, not a new thing. Lavoisier lost his head in the French Revolution, Galileo had an encounter with the Inquisition, Servetus was burned at the stake, and as recently as 1942 Vavilov died in a Siberian concentration camp in martyrdom for his views in genetics.

Are scientists who take bold public action merely meddlers and busy-bodies or is their concern and responsibility for the consequences of research a logical extension of scientific enterprise? Most scientists are voters and citizens and as such are entitled to express opinions freely on any matter. However, modern scientists are accused of "pulling rank" by implying that because of their participation in the experimental phase of a particular scientific development they may express with extraordinary authority their convictions as to what the social implications of these developments should be. "Pure" scientists should, by this argument, restrict their professional activities to the confines of their laboratories.

That scientific findings do have an immediate and overwhelming impact on society in areas other than atomic power is apparent. In yesterday's mail was the Annual Report from an insurance company which stated that last year only twenty per cent of the deaths of its policyholders came as a result of infectious diseases. This compares with thirty-one per cent in the decade of the thirties and forty-one per cent in the twenties. This sharp mortality drop came largely as a result of the effectiveness of treatment with penicillin and the sulfa drugs.

Who guides and directs this terrific impact of scientific findings on the welfare of our society? What lies between the original observations made by laboratory workers in medical schools and research centers that bacteria cannot grow and divide in the presence of certain chemical compounds, on one hand, and the total effectiveness of these chemicals in eradicating sickness and misery from the world on the other? Does the responsibility for achieving wise, humane and universal application lie with the scientist, his college or university, the government, pharmaceutical supply houses, medical societies?

The high cost of penicillin and many other extremely effective drugs limits the extent to which they can achieve maximum usefulness. To add to this unfortunate situation, the profit taken by the sale of drugs does not in any direct way benefit those medical and research institutions where often the original discoveries are made. Our best medical schools must train doctors, carry on research, and develop clinical procedures all on a fraction of the budget of a second-rate drug firm. This inequality between the rewards for original investigation and the income derived from the application of those studies may well stem directly from the original research worker's lack of interest in the eventual consequence of his investigations. Everyone would benefit if the same enthusiasm and earnestness of purpose which characterize "pure" research were applied to the job of seeing that the products of that research were distributed in such manner as to bring the greatest good to the greatest number.

Another argument advanced to encourage participation of scientists in public affairs is that the inherently international nature of scientific enterprise works for easy and effective understanding between individuals engaged,, in scientific pursuits irrespective of their nationalities. Whereas an individual artist, economist, poet or musician has the heritage of his particular culture ingrained in him with its peculiar bias, nuances and values, the individual physicist, mathematician, psychologist, geologist or biologist can talk on absolutely common ground with any other scientist irrespective of his nationality or social inheritance. This understanding which is easy and natural for scientists could perhaps be used much more widely than it now is for the formation of international good will.

Today, unfortunately, censorship, restrictions on travel and interference with the free exchange of scientific publications are all thwarting the inherent international nature of science. Beyond this, attempts are now actively being made to endow science with national and class characteristics. For example, in a recent Pravda article the inference is clear that there exists a peculiar kind of Russian biology distinct in quality from the biology of other nations, and a special kind of science which belongs to one social class and different from that of other classes. "Every Soviet biologist," the article states, "will resolutely rise against such an obviously wrong, clearly antipatriotic representation of the Soviet biology. ... A certain backward part of our Soviet intelligentsia still carries a slavish servility for bourgeois science, which is profoundly foreign to Soviet patriotism." This jingoistic journalist, Laptev, was referring to Anton R. Zhebrak, an internationally-known Soviet geneticist who had said in a scientific periodical: "Together with American scientists, we, working in the same field of science in Russia, are building a general biology on a world-wide scale."

To the scientist who enters into public affairs comes the inevitable assumption of new risks and responsibilities However, such participation is to be encouraged if it contributes in any way to a world in which the results of scientific discovery are more wisely and humanely applied and in which universal understanding and good will prevails.

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ZOOLOGY

Professor Forster, chairman of the Division of the Sciences at Dartmouth, has recently been granted a Guggenheim Fellowship for special research during 1948-49. As part of his project, he plans to compare notes with scientists abroad, thus promoting the international science which he writes about in his editorial.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE MEANING OF TOLERANCE

May 1948 By W. K. JORDAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Article

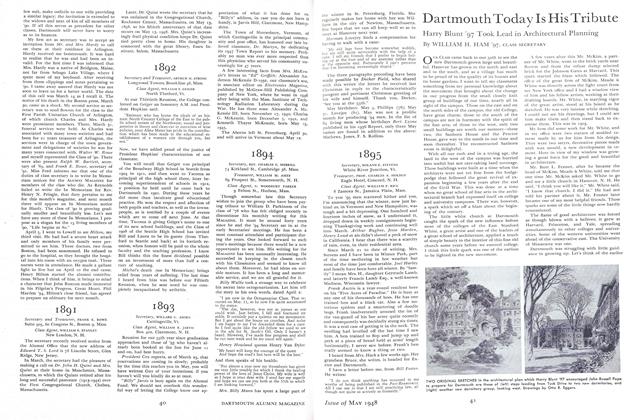

ArticleDartmouth Today is His Tribute

May 1948 By WILLIAM H. HAM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

May 1948 By J. K. HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON, ROSCOE A. HAYES -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

May 1948 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II -

Article

Article"Pest House" Days

May 1948 By ALICE POLLARD

ROY P. FORSTER

Article

-

Article

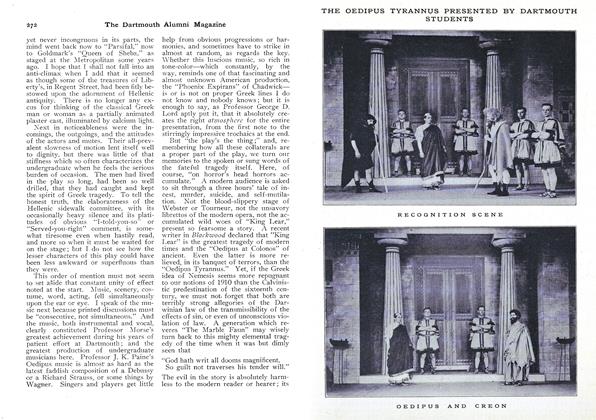

ArticleTHE OEDIPUS TYRANNUS PRESENTED BY DARTMOUTH STUDENTS

May, 1910 -

Article

ArticleASSOCIATIONS OF SECRETARIES

January 1924 -

Article

ArticleInaugural Delegates

April 1949 -

Article

ArticleHospital move given conditional approval

September 1986 -

Article

ArticleWinter Sports Success in 24th D.O.C. Carnival

March 1934 By Emerson Day '34 -

Article

ArticleWhere the Grass Looks Green

May 1975 By JACK DEGANGE