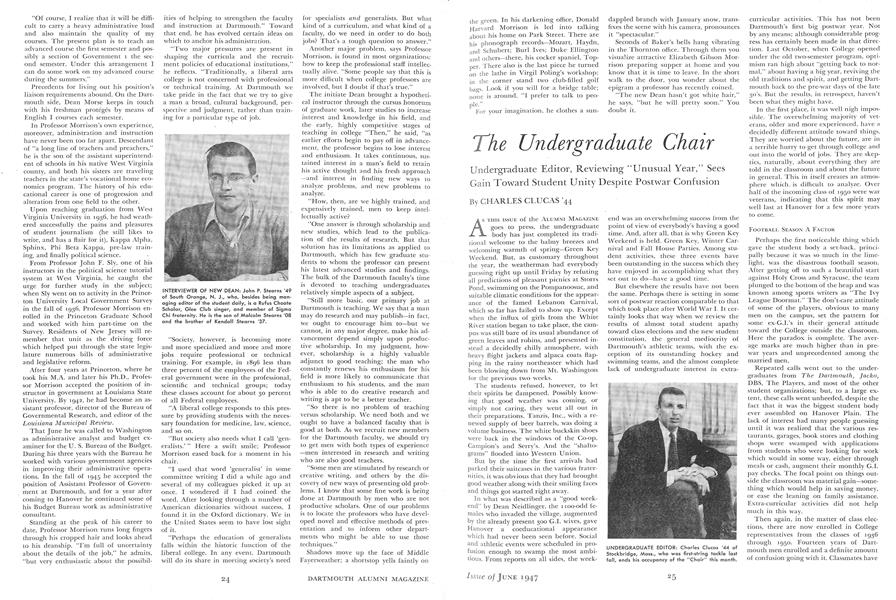

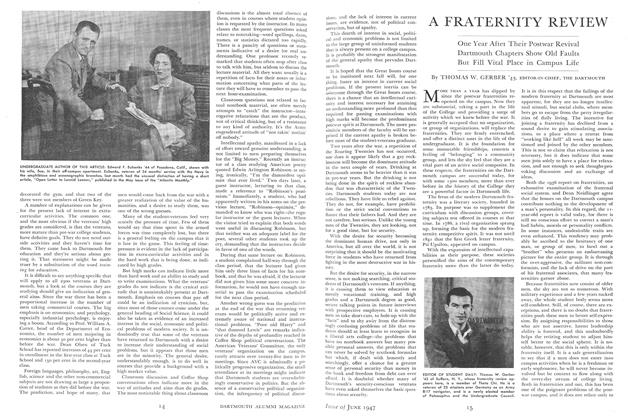

Prof. Donald H. Morrison, Public Administration Expert, Who Succeeds Dean Bill at 32, Gives Some of His Views on the Challenging Job Ahead

IN THE SLUSHY denouement of April, Donald Harvard Morrison, Assistant Professor of Government, could lean back contentedly from the technical and personal paraphernalia which nearly two years at Dartmouth had brought to his desk in Thornton Hall.

His courses in various phases of public administration had been successful; the book he had helped to write last year, TheUnited States at War, had received professional acclaim; in a few weeks, his solid, compact figure would start striding through a second summer of golf on the links up Rope Ferry Road. Quietly, sensibly, things were going well.

But before the first flag had dropped over a fairway, Professor Morrison's career received an unexpected turn at the hands of President Dickey. On April 24, College and town learned that the 32-year-old professor would succeed E. Gordon Bill as Dartmouth's Dean of the Faculty.

Until July, however, when the threeman interim committee appointed to carry on during Dean Bill's long illness steps down, the new Dean will continue his teaching operations from his office overlooking the third floor of Middle Fayerweather Hall.

After the first few minutes of talking with him talking that comes easily you realize suddenly why the community of Hanover received the news of his appointment with some surprise but with general approval. For the warm, friendly smile that flows over his long face at frequent intervals, the air of energy and earnestness about him, speak strongly of his youthfulness; the way he looks off for a minute, digesting a question, his smooth, deliberate gestures in answering it, and above all, the careful, tactful, precise quality of the answer itself, speak just as strongly of experience and wisdom.

In the maze of a Dean's duties, Professor Morrison will find ample use for both of these general attributes. The Dean of the Faculty, fundamentally, is the connecting link between professor and President. As such, he will preside over faculty meetings in Dr. Dickey's absence; in collabo- ration with the department chairmen, he recommends new teachers to the President and Trustees; he serves as chairman of the Committee Advisory to the President and as a member of the important Committee on Educational Policy; he must approve all examinations given in the College; beyond that, there are the countless "little duties" attendant on a job as yet unmolded by long tradition.

And yet, Professor Morrison, whose students called him "enthusiastic and interesting" in The Dartmouth's recent survey of courses, hopes to go on as teacher as well as administrator. For that desire, he advances several reasons.

"First, I want to develop my competence in public administration and one way of doing that is to teach.

"Second, there are certain faculty problems that the Dean can appreciate more easily if he teaches—for instance, those arising out of the interests, points of view and reactions of undergraduates.

"Third, I like to teach. The give and take of classroom discussion, the explanation of complex problems to students who want to learn, the feeling that one is helping a student develop intellectually—all of this gives me a personal satisfaction that I get in no other way.

"Of course, I realize that it will be difficult to carry a heavy administrative load and also maintain the quality of my courses. The present plan is to teach an advanced course the first semester and possibly a section of Government 1 the second semester. Under this arrangement I can do some work on my advanced course during the summers."

Precedents for living out his position's liaison requirements abound. On the Dartmouth side, Dean Morse keeps in touch with his freshman proteges by means of English I courses each semester.

In Professor Morrison's own experience, moreover, administration and instruction have never been too far apart. Descendant of "a long line of teachers and preachers," he is the son of the assistant superintendent of schools in his native West Virginia county, and both his sisters are travelingteachers in the state's vocational home economics program. The history of his educational career is one of progression and alteration from one field to the other.

Upon reaching graduation from West Virginia University in 1936, he had weathered successfully the pains and pleasures of student journalism (he still likes to write, and has a flair for it), Kappa Alpha, Sphinx, Phi Beta Kappa, pre-law training, and finally political science.

From Professor John F. Sly, one of his instructors in the political science tutorial system at West Virginia, he caught the urge for further study in the subject; when Sly went on to activity in the Princeton University Local Government Survey in the fall of 1936, Professor Morrison enrolled in the Princeton Graduate School and worked with him part-time on the Survey. Residents of New Jersey will remember that unit as the driving force which helped put through the state legislature numerous bills of administrative and legislative reform.

After four years at Princeton, where he took his M.A. and later his Ph.D., Professor Morrison accepted the position of instructor in government at Louisiana State University. By 1942, he had become an assistant professor, director of the Bureau of Governmental Research, and editor of the Louisiana Municipal Review.

That June he was called to Washington as administrative analyst and budget examiner for the U. S. Bureau of the Budget. During his three years with the Bureau he worked with various government agencies in improving their administrative operations. In the fall of 1945 he accepted the position of Assistant Professor of Government at Dartmouth, and for a year after coming to Hanover he continued some of his Budget Bureau work as administrative consultant.

Standing at the peak of his career to date, Professor Morrison runs long fingers through his cropped hair and looks ahead to his deanship. "I'm full of uncertainty about the details of the job," he admits, "but very enthusiastic about the possibilities of helping to strengthen the faculty and instruction at Dartmouth." Toward that end, he has evolved certain ideas on which to anchor his administration.

"Two major pressures are present in shaping the curricula and the recruitment policies of educational institutions," he reflects. "Traditionally, a liberal arts college is not concerned with professional or technical training. At Dartmouth we take pride in the fact that we try to give a man a broad, cultural background, perspective and judgment, rather than training for a particular type of job.

"Society, however, is becoming more and more specialized and more and more jobs require professional or technical training. For example, in 1896 less than three percent of the employees of the Federal government were in the professional, scientific and technical groups; today these classes account for about 30 percent of all Federal employees.

"A liberal college responds to this pressure by providing students with the necessary foundation for medicine, law, science, and so on.

"But society also needs what I call 'generalists.'" Here a swift smile; Professor Morrison eased back for a moment in his chair.

"I used that word 'generalist' in some committee writing I did a while ago and several of my colleagues picked it up at once. I wondered if I had coined the word. After looking through a number of American dictionaries without success, I found it in the Oxford dictionary. We in the United States seem to have lost sight of it.

"Perhaps the education of generalists falls within the historic function of the liberal college. In any event. Dartmouth will do its share in meeting society's need for specialists and generalists. But what kind of a curriculum, and what kind of a faculty, do we need in order to do both jobs? That's a tough question to answer."

Another major problem, says Professor Morrison., is found in most organizations: how to keep the professional staff intellectually alive. "Some people say that this is more difficult when college professors are involved, but I doubt if that's true."

The initiate Dean brought a hypothetical instructor through the cursus honorum of graduate work, later studies to increase interest and knowledge in his field, and the early, highly competitive stages of teaching in college "Then," he said, "as earlier efforts begin to pay off in advancement, the professor begins to lose, interest and enthusiasm. It takes continuous, sustained interest in a man's field to retain his active thought and his fresh approach and interest in finding new ways to analyze problems, and new problems to analyze.

"How, then, are we highly trained, and expensively trained, men to keep intellectually active?

"One answer is through scholarship and new studies, which lead to the publication of the results of research. But that solution has its limitations as applied to Dartmouth, which has few graduate students to whom the professor can present his latest advanced studies and findings. The bulk of the Dartmouth faculty's time is devoted to teaching undergraduates relatively simple aspects of a subject.

"Still more basic, our primary job at Dartmouth is teaching. We say that a man may do research and may publish in fact, we ought to encourage him to but we cannot, in any major degree, make his ad: vancement depend simply upon productive scholarship. In my judgment, however, scholarship is a highly valuable adjunct to good teaching; the man who constantly renews his enthusiasm for his field is more likely to communicate that enthusiasm to his. students, and the man who is able to do creative research and writing is apt to be a better teacher.

"So there is no problem of teaching versus scholarship. We need both and we ought to have a balanced faculty that is good at both. As we recruit new members for the Dartmouth faculty, we should try to get men with both types of experience men interested in research and writing who are also good teachers.

"Some men are stimulated by research or creative writing, and others by the discovery of new ways of presenting old problems. I know that some fine work is being done at Dartmouth by men who are not productive scholars. One of our problems is to locate the professors who have developed novel and effective methods of presentation and to inform other departments who might be able to use those techniques."

Shadows move up the face of Middle Fayerweather; a shortstop yells faintly on the green. In his darkening office, Donald Harvard Morrison is led into talking about his home on. Park Street. There are his phonograph records—Mozart, Haydn, and Schubert; Burl Ives; Duke Ellington and others there, his cocker spaniel, Topper. There also is the last piece he turned on the lathe in Virgil Poling's workshop; in the corner stand two club filled golf bags. Look if you will for a bridge table; none is around. "I prefer to talk to people."

For your imagination, he clothes a sundappled branch with January snow, transfixes the scene with his camera, pronounces it "spectacular."

Seconds of Baker's bells hang vibrating in the Thornton office. Through them you visualize attractive Elizabeth Gibson Morrison preparing supper at home and you know that it is time to leave. In the short walk to the door, you wonder about the epigram a professor has recently coined.

"The new Dean hasn't got white hair." he says, "but he will pretty soon." You doubt it.

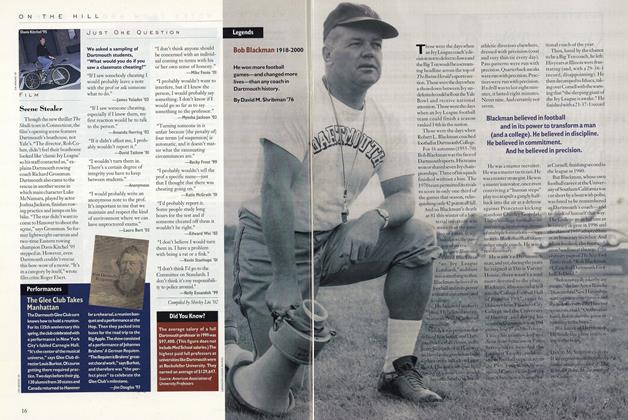

PROF. DONALD H. MORRISON, WHO BECOMES DEAN OF THE FACULTY ON JULY 1

INTERVIEWER OF NEW DEAN: John P. Stearns '49 of South Orange, N. J., who, besides being managing editor of the student daily, is a Rufus Choate Scholar, Glee Club singer, and member of Sigma Chi fraternity. He is the son of Malcolm Stearns 'OB and the brother of Kendall Stearns '37.

MANAGING EDITOR, THE DARTMOUTH

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA RIVER CAMPUS?

June 1947 By PETER E. COSTICH '47 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

June 1947 By J. K. HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

June 1947 By DONALD C. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD -

Article

ArticleTHE TIRED VETERAN

June 1947 By EDWARD F. EUBANKS '44 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

June 1947 By FRED F. STOCKWELL, WILLIAM T. MAECK

JOHN P. STEARNS '49

Article

-

Article

ArticleMINISTER INSTALLED

APRIL, 1908 -

Article

ArticleROTARY-CLUB ORGANIZES CHAPTER IN HANOVER

May 1925 -

Article

ArticleNot October Scene, But It Won't Be Long Now

October 1942 -

Article

ArticleA GREAT CAST FOR "FLICK'S 84"

MAY 1965 -

Article

ArticleJust One Question

JUNE 2000 By Shirley Lin '02 -

Article

ArticleCongratulations

February 1935 By The Editors