Our greatest resources are to be found in those abstractions underlying a liberal society...." Seniors are told by distinguished historian in Great Issues Course lecture

SINCE we are about to discuss a topic that can still engender some heat and about which one can be very abstruse, I think we ought at the outset to define our terms. Indeed, the word "tolerance" itself is so abstruse that I doubt whether it ought ever to be used in a discussion requiring precision of meaning without adding a qualifying adjective. May I say, first of all, that I am speaking this evening principally of religious tolerance. Let us then proceed to definitions.

I take it, for example, that the term philosophical tolerance may be said to possess definable content. By it we presume, a mind which has definite and pronounced religious convictions, but which is able and willing to concede to other minds the moral right to retain, practise, and disseminate contrary religious beliefs thought to be held in error. This attitude of mind can be attained only by an Olympian intelligence and has in point of fact never, until comparatively recently, characterized the thought or policy of a Christian communion in a dominant position in any society. It is a state of mind, doubtless admirable and interesting philosophically, but possessing little historical significance.

Of much greater importance for our consideration is legal toleration, or perhaps more accurately historical toleration. In its historical and legal context the term simply signifies a refraining from persecution. It therefore requires no nobility of motive on the part of the person or the society that is tolerant. It suggests at least latent disapproval of the belief or practice which is tolerated; it presupposes a volitional action on the part of a dominant party with respect to a weaker; it implies voluntary inaction on the part of a dominant group; and it necessarily arises from complex social and historical sources.

Then finally we must note that absolute religious liberty is the probable but not the necessary outgrowth of toleration. It is I think possible only in a society in which there exists widespread indifference, a pervading scepticism, and a forswearing by the state of any responsibility for the spiritual destiny of its inhabitants. When this stage is reached the question of legal toleration has ceased to have any save historical interest. We stand today in America and in England well within the threshold of religious liberty.

We shall spend most of our time today examining the rise of religious toleration because it was in this area that mankind first learned to discipline powerful and basic sentiments as the price of its own survival and because the great problem of tolerance in general has been most fruitfully and successfully worked out in this respect. Further, we can view the development of religious toleration with reasonable objectivity and with the great advantage lent by historical perspective. We shall examine its rise in England because the great struggle was first resolved there in a pattern which we and all other liberal societies have accepted as an integral part of our inheritance.

Being an historian I shall of course have to talk for too long about the medieval background. But in this case, I can assure you that it is relevant. We must recall that in the medieval view the church and the state were joint and divine instruments dedicated to the attainment of man's salvation. The church embraced all mankind, its institutions permeated and framed the whole of a culture, and its precepts and sacraments sustained the faith of all men. The church taught a body of truth held to be essential to salvation and in so doing enjoyed the support of every instrumentality that could possibly assist in the attainment of its high ends. The church, moreover, was universally regarded as possessed of infallibility of knowledge and as ordering the will of God on this earth. Consequently, a heresy, which may be defined as the wilful denial of a doctrine essential to salvation, could only be regarded as a dangerous instance of moral rot which must be exterminated lest it spread and lest truth itself be profaned. You will agree, I think, that a logical and unanswerable case could be drawn for the extirpation of heresy so long as a whole society remained dedicated to the primary postulates of the Middle Ages, and so it was.

But the Reformation movement, beginning in the early sixteenth century, speedily introduced difficulties at once theoretical and practical into the medieval ethic. Lutheranism and especially Calvinism were not tolerant faiths, because they too claimed to teach an exclusive and an absolute system of truth outside which salvation could not be gained. But as they developed and as larger and larger areas were won by them from the historic church, a factual situation was created which rendered absurd the medieval ethic and bore most violently on generally accepted axioms of political theory. To put it very bluntly there was no longer a truly catholic [i.e.. universal] church; there were rather an increasing number of communions all of which claimed to be catholic and all of which undertook for reasons of faith to proscribe heresies. The inevitable result in all parts of western Europe, save England, was a terrible scourge of civil and national wars, animated by faith and prosecuted with crusading zeal which while pretending to maintain intact the seamless robe of Christ very nearly destroyed western civilization. I think most historians agree that the hundred years of almost constant warfare, culminating in the Thirty Years' War, laid upon mankind the most awful terror that it has known. It became apparent towards the end of this period that if civil communities were to survive and if public order were to be maintained, zeal must be restrained within the chains of some sort of legally imposed toleration.

It was in England through a fortuitous grouping of circumstances that the struggle for religious toleration was first won and the accommodation of thinking to the basic realities of the modern age first accomplished. Religious toleration came to be accepted in England as a political necessity by wise and prudent monarchs who were primarily interested in the building of a strong civil power and who understood that if their kingdom were to escape the holocaust then sweeping the Continent the religious emotion must be strictly controlled by the state for essentially secular ends. This fact accounts for the settlement of religion by Elizabeth in 1559, in a truly Erastian mould. The constitution of the Church of England therefore was comprehensively framed in order to include all reasonable men. Its doctrines were left rather vaguely defined and no attempt was made to impose tests of belief on the conscience of the laity. The government did require occasional conformity in attendance at divine services, but it tried to make it clear that this was a civil action which bore no necessary relation to the beliefs of the communicant. Moreover, the Elizabethan Settlement was imposed by Parliament, i.e., by laymen, and it was made abundantly clear that the tolerant circumference of faith included in the Settlement-might at any time be further enlarged if occasion should so require.

During these years, it is important to note, England was struggling with fanaticism. She was engaged in a war to the death with Spain, and Spain, as you will recall, was the spearhead of the Counter-Reformation, of Catholicism striking back. It was therefore important that the government should define its objectives as precisely and as clearly as possible, and this Queen Elizabeth did. She made it clear that she would not attempt to ferret out men's inner beliefs, would not raid their consciences, and would not persecute ideas. But she also made it very clear that she would not tolerate sedition. She drew the line of treason with very great care and then enforced the statutes against treason. For the first time, consequently, in the history of the western world, men came to discover a separation between their faith and their political loyalties. And finally, the English Government was constrained in repeated statements—and this was very revolutionary—to disclaim any responsibility for the salvation of its subjects, thereby stripping away all the moral power and fervor which heretofore had armed the persecutor. In brief, then, the basic cause for the development of legal toleration in England was the political necessity which dominated the thinking of a wise and a very hard-boiled monarch.

But there were other causes that emerged in the period 1550-1660 which may appear to you somewhat more noble. The second of the underlying causes was the very rapid growth of rationalism and scepticism. There were in England by 1640 not fewer than four Christian communions, or sects, each aspiring to control of church and state, all bitterly attacking each other, and all, save one, propounding a theory of religion essentially medieval and intolerant. The structure of absolute truth had patently been shattered, there were too many conflicting systems of infallible faith, and there had been a pronounced deterioration in the quality and sensibility of ecclesiastical argument. Out of this background there speedily developed a lay intelligence which swept aside the whole classical position of religious and political theory and which approached the transcendent problems with a fresh, an intensely objective, and an occasionally violent scepticism. This revolution in thought gained way very rapidly in the seventeenth century and began a weakening of the vitality of organized Christianity which has perhaps not fully run its course even today.

Thirdly, the confusion, the bickering, and the disagreeable intolerance of the sects helped to account for the spread in England of a religious indifference which could be mild or complete. I think it fair to say that in 1600 there is almost no instance that can be demonstrated of true religious indifference, whereas in 1660 it was already coming to pervade thought. Men very often used the same terms as their fathers, observed at least infrequently the religious rituals, but vitality of faith had fled from them. The historian of ideas must almost certainly say that it was the slow diffusion of religious indifference that finally settled the question of religious toleration in England. The indifferent man is tolerant of all religions because he lends his devotion to none. Indifference is the most deadly of all the enemies of faith; it offers no front which may be attacked; it declines to join with an issue which it does not even recognize. Zeal in England and in western Europe was to burn itself out in that profound reaction which is the eighteenth century.

In estimating the forces which in their totality won the battle of religious toleration I should also mention the profoundly important development of the view that the individual man possesses an essential dignity and integrity of his own. Many forces were conjoined to establish for the individual man a new nobility, but certainly amongst them was the notion that every man should be permitted to find salvation in his own way. Elizabeth contributed to this development by allowing political necessity to fashion the extent of her repression and by scrupulously confining her wrath to the bounds set by the law of treason. Elizabeth was ever moved by politics and not by piety; her courts dealt with facts and not with opinions; there was no moral content in Elizabethan repression which, ironically, was to constitute a very great moral gain in the history of culture. The individual man became the lowest common denominator of faith, with the result that any system of persecution could only be regarded with philosophical abhorrence.

The great gain of religious toleration was won slowly, at very great cost, and only after it, with other forces, had destroyed the essential structure of an earlier civilization. It could prevail in England only after all communions, and especially the Roman Catholics, had consented or had been compelled to renounce their claim to a universal hegemony over the souls of man and had been driven by the inexorable tuition of history to accept a sectarian status in the civil community. It was in these ways that toleration became one of the great pillars supporting the liberal society of which you and I are part. The great struggles which won for man his constitutional, legal, and intellectual freedom could not possibly have been gained had not a bloodier and on the whole a more significant struggle gained for him the birthright of spiritual freedom. Men learned in the seventeenth century that religious toleration was the price that must be paid for their own survival and for the survival of the modern state. It was only then that legal toleration, perhaps ignoble in its origins, could slowly expand into the liberty of religion which we prize today.

All this background was known and understood by the founders of this republic who, seeking to erect a liberal society, took the most specific care that they should forever disclaim for the state any responsibility or direct concern for the spiritual activities or even welfare of its members. These founders were possessed of a more accurate and certainly a more eloquent understanding of the grim history of the struggle than the majority of the Supreme Court which so recently and so inadequately attempted to review it for us. The first amendment to the Constitution lies imbedded as the necessary cornerstone of a liberal society. Those who drafted that amendment knew they were being bold men when they sought to leap ahead of the slow progress of the western European societies by implanting in our Constitution the doctrine of the absolute separation of church and state.

My sketch has been long because we must constantly examine the nature of our heritage if we are to use it and defend it. Our culture rests on abstractions, at bottom, that have been won and vindicated for us by great suffering, much bravery, and the slow gains of history. They pose the great issues for us, since it may be truly said that they are the great issues. You may well say, this is the stuff of history—a remote annal of our past which may record accurately how our forebears solved one great and terrible problem, but it bears no relevance to the issues of my day. But is this true? Is this not to be insensitive to the requirements of our own inheritance?

Shall we attempt some applications? I know that you will shortly read the opinions handed down in the recent case of Everson v. Board of Education of Ewing Tp. The separation of church and state, including public education, is clear, clean, and complete in our history and in our Constitution. No glossing by lawyers and no twisting of legal mystaphysics can obscure this reality. The Roman Catholic communion, like many others, enjoys in this country the status of a sect and it, like all others, is factually and legally not a church in the historical meaning of that term. Moreover, this communion like all others enjoys religious freedom and complete liberty of worship and a complete circumference under law of spiritual' activity. The nature of its powers and capacities in this and all other liberal societies differs fundamentally from that in those countries where it remains a church and where its great powers of the past are not yet diminished by the complete separation of church and state. Therefore the majority opinion in the Everson case sets into the structure of a liberal society a thin wedge which offers the very gravest of dangers to the nation and which does violence to gains won at such terrible cost. But this consideration I had best leave to your reading and the discussion which I am sure will be aroused by it.

Now shall we attempt a much more difficult application? How does what I have said about the slow development of tolerance in religious matters apply to our efforts to grasp intellectually and to handle politically what I suppose all of us would regard as the danger of communism? Can we translate past experience into terms of present realities? We must proceed very carefully if we try to do so. We are having great difficulties in our generation, just as the Elizabethan generation met a great crisis. We are finding it hard to examine our thinking and to frame a philosophy and a policy with respect to militant communism. We have forgotten how disagreeable, how dangerous, and how completely illiberal fanaticism can be. Our forefathers knew a great deal about that: there are some interesting comparisons to be made between the communists of our age and the Christian communions of the midsixteenth century.

The communists, we should observe, are dedicated men. We must not forget that. They are men who have been caught up with a vision'of what they hold to be absolute truth. Furthermore, they have contrived all the apparatus and all the powerful stimulation that accrues from what I think we can describe as the church concept. They have drawn much strength from the ideal of the Middle Ages and they do have all the apparatus of the medieval church. They have the definition of heresy, sharp, clean, and clear. They excommunicate when they cannot extirpate the heretics. They have a well-fashioned dialectic. They possess organic strength and finally, and again the comparison runs true, they are imbued with a crusading will. We indeed—we liberals—are not so much heretics as we are unbelievers, and again the medieval comparison runs true.

The liberal society must learn very quickly, as the English society one time did, to distinguish between the ideas, the beliefs, and the actions of communists here and abroad. I think we must learn to apply in our own thinking and in our own policy the Elizabethan formula. A war, of ideas is raging in the world around us today. We cannot destroy a militant fanaticism in this case by indifference, because fanaticism has not yet burned itself out. It is, I think, indispensable to our own integrity and to our own survival that we tolerate the ideas of communism, that we assess its efforts, that we examine what it propounds as truth, just as Elizabeth encouraged disputations between the Catholics and the Protestants in,order to give vent to repressed emotions and to let truth discover itself. So I think we too should examine as carefully as we can the ideas that arm this new faith. Indeed our own inheritance and our own conception of the nature of truth require us to levy no war on thought, however erroneous that thought may seem to us. There are grave, there are terrible dangers in persecution, as I have tried to demonstrate. Persecution creates martyrs, persecution compresses ideas until they have immense explosive power, but above all the gravest damage is done not to the persecuted but to the persecutor. The weapons we would have to muster to persecute thought would destroy us in the very act of saving ourselves. The free sifting of ideas by reason, then, is part of our inheritance and is an essential postulate underlying the institutions of a free people. The light of reason must play on all ideas. If we renounce this doctrine, we have renounced liberalism itself. We must not be gripped by hysteria; there must be no intellectual witch hunt. We have nothing whatever to fear from the teachings or the ideas of the communists. If we have, we are doomed as free men. That, I think, is historically the liberal tradition. It is, I think, factually the liberal necessity.

But that is not quite the whole of the story. We must differentiate, as the English government learned it must, between belief and action. We should punish as criminal activities any illegal actions which offer manifest danger to our state and to our society, not, please observe, as communistic ideas, but as crimes against the state and against the substance of sovereignty. That is not only common prudence; it is an exercise by sovereignty of the very nature of sovereignty. We are armed with the strength of a great and a noble inheritance which has created in this world a fit habitation for free men. Our resources of the spirit are, I think, infinitely greater than the material strength of which we like sometimes to boast and which we are occasionally disposed to throw about a bit recklessly. Our greatest resources are to be found in those abstractions underlying a liberal society which have been refined by time, tested by events, and which are part of our almost instinctive inheritance. And the greatest of all these resources is the glorious fact that the tolerant man is also a free man, a man not easily corrupted, not easily misled, and not easily made afraid of his own destiny.

PRESIDENT OF RADCLIFFE COLLEGE

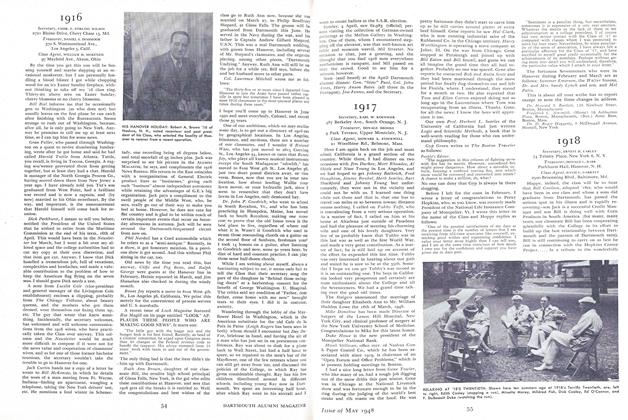

DR. WILBUR K. JORDAN, PRESIDENT OF RADCLIFFE COLLEGE

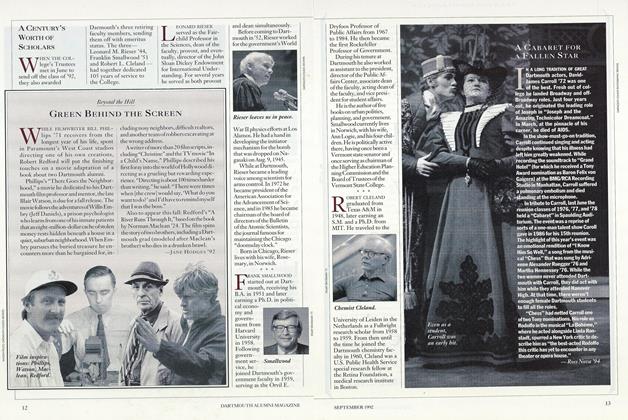

ON A VISIT TO THE PUBLIC AFFAIRS LABORATORY, Nelson Rockefeller '30, Great Issues lecturer of March 22, discusses the news with a senior. Standing is Alexander Laing '25 and seated right is Prof. Arthur M. Wilson, respectively steering committee member and associate director of the course.

President Jordan's Great Issues lecture was given on March 8 as part of the course's consideration of the general topic, "American Aspects of World Peace." Together with the preceding lecture by Thomas W. Braden '40 on "The Meaning of Liberalism," it provided a discussion of underlying principles after the class had taken up civil rights and labor unions and before it moved on to the issue of public planning.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Today is His Tribute

May 1948 By WILLIAM H. HAM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

May 1948 By J. K. HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON, ROSCOE A. HAYES -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

May 1948 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II -

Article

Article"Pest House" Days

May 1948 By ALICE POLLARD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924

May 1948 By JAMES T. WHITE, RICHARD A. HENRY, DONALD E. COYLE

Article

-

Article

ArticleBISHOP TALBOT '70 AT HEAD OF CHURCH

April 1924 -

Article

ArticleAN OIL PORTRAIT of Sidney C. Hayward

MAY 1963 -

Article

ArticleThird Composer for Summer.

MARCH 1967 -

Article

ArticleA Century's Worth of Scholars

September 1992 -

Article

ArticleHanover 1948

May 1948 By C. M. WILSON '11 -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

October 1973 By J.H.