Assistant Professor of English, Dartmouth College

In these days when writers and artists are vigorously "combing" America for color and backgrounds, there exists a great background truly American, as full of life, romance, and color as any oldworld city, which needs only the touch of a true gifted American to reproduce it in verse, novel, statue, or song. This is a background which might give a real American literature to the world. It is the background of Indian life.

No great national literature has ever arisen which lacked a national background. The old world countries with their centuries of existence easily provided the backgrounds for great artistic works. The legends of the early Britons and Anglo-Saxons provided the soil in which English literature grew. Russian literature would have been impossible without the old songs of Kiev and the Nestor Chronicles. The old stories which were handed down through the centuries by word of mouth or writing inspired the literary movements of the modern world. America has just such a soil as that, ready for culture, a soil perhaps too obvious to most of us in the midst of the rush which the age of commercialism has brought. MacDowell sensed it,—Longfellow gave us our only Indian epic of any value,—a few paint- ers and sculptors have delved in it still more, but usually in conventional and commonplace ways.

But Dartmouth College is built upon this soil. It was established in the spirit of a man who was one of the greatest liberals and men of action of his time,— it is strange to think of Eleazar Wheelock as a liberal, yet he saw in the days when the common attitude of the white race towards the Indian was an attitude of oppression and conquest,—he saw in such a time a vision of a great equality, and he moved into the very haunts of the red race in order to carry out his ideas. His ideals were those of the early missionary; he had the tender heart of a man of great compassion, for although he might himself have ascribed his unconquerable determination to a sense of duty to God and religion, yet his very acts stamp him as a great humanitarian, a man who like William Penn and Roger Williams made friends with the people that had up to his time been regarded as the foes of the white race.

Few American institutions can boast foundation upon such a great principle of tolerance. And while the experiment of "educating the Indians" seemed to fail, yet it did not fail in this sense,— that it has helped to preserve among us the heritage of the red race, the race that loved freedom and broad horizons beyond anything else in the world, the race that, although at times desperately cruel and barbarous, yet had in its heart the very life-giving fundamentals that are necessary to any civilization, no matter how "cultured," "refined," glossed-over, or polished, we may become.

Dartmouth's very great tradition is the tradition,—no, history,—which connects the College with the Indian life. These traditions may be obtained today from descendants of the first Indians who went to Dartmouth. Tomorrow—it will not be possible. It is within the power of Dartmouth men today to rescue these Indian records from the temporary oblivion into which they have passed. Dartmouth is great in accomplishment, in scholarship, in the men that made her proud, and yet Dartmouth lacks the chronicling of the lives of the first Americans, the men for whom Dartmouth was founded, some of whom carried the light from her shrine into the wildest of forest wildernesses.

The traditions of the College thus do not go back merely to 1769. They go back through that date into the hearts of the men who lived in America before the white races came. For there is in that unexplainable thing called "Dartmouth Spirit" the touch of mystery, the sense of things once known but now forgotten, the feeling of a great freedom,— Richard Hovey caught it best of all the sons, but it did not come to him merely through his kinship with nature, through his familiarity with the traditions,—it had to be first translated into terms of human feeling before he caught it,—and the element in the charm of the College which gives piquancy to that charm is the spirit of the old Indian life, its reflection of nature about it, the impressions of the rock-rooted hills and the breath of the winds.

Indians brought that tradition to Dartmouth. And there are descendants of those Indians living today among the Indian races on the St. Francis reservation in Canada, and elsewhere who can still interpret in words the lingering secrets of the Indian race.

There are the legends about the country of the old "battlefield" of the Indians on Mt. Support on the Lebanon Road. Relics of the old life have been found on the plain on Mt. Support, at the entrance to Mink brook, and on the islands in the river. Two men who served Dartmouth College with all the gifts of their rich lives, Alpheus P. Crosby, and Oliver P. Hubbard, knew some secrets of the old Indian settlement on Mt. Support that may never be divulged. In another hundred years all the old reports will have been lost. Therefore at the present time, the key to one of Dartmouth's fine traditions may possibly be found, but it must be found in this generation.

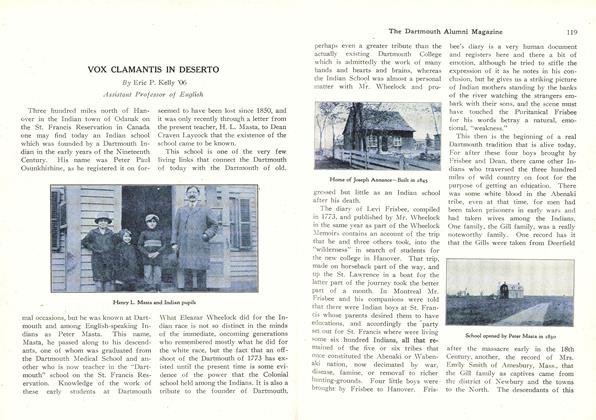

Henry L. Masta of Odanak, Province of Quebec, Canada, himself a descendant of a Dartmouth Indian who went into that wilderness in the latter years of the 18th Century sings a praise of Dartmouth College that but few of her sons can equal. He tells of the work of Dartmouth men in educating and bringing the light to Indians who were driven before the armies of the white man from Maine to New York. Until Dartmouth College was founded, most of these Indians had nothing but a spirit of hatred against the white invaders who had stolen from them, robbed them of their women, slaughtered them, burned their towns. In the early colonization of America the white man's treatment of the red is a most disgraceful thing,— it is compensated no wee bit by the fact that the Indians. were spiteful in their turn. There is a record of a colonial officer who allowed an Indian woman to be torn to pieces by dogs before his face. Is there anything in the treatment of Indians by white men more shameful than that?

Dartmouth's doors since the beginning have been open to every race, creed, color,—God grant that they may always be so open!

But the Indians on the reservation today still look towards Dartmouth, much as the Moslem looks towards Mecca. Mr. Masta himself only a few days ago in sending a record of Dartmouth descendants on the reservation voices the praise of the College in no uncertain way. With such a splendid tradition as its beginning, with such a principle, and with such concrete evidences of that work today, it is the' duty of every Dartmouth man to lay hand upon and send back to the College any scrap of paper that can in any way help to give the College the record of that work. One manuscript, today of the highest value to the College, was lent to President Dwight of Yale College. A graduate of the class of 1773 compiled in that manuscript an account of the old Indian mythology. The graduate was himself an Indian. The manuscript "is believed to be lost" according to G. T. Chapman, whose book on the history of the alumni appeared in 1867. Would that it might be found!

Work on the Indian material will be carried forward, but the alumni are asked to help in the work. If any graduate of the College knows a person who has information concerning any of the lost traditions or of early Indian students that information will be most gratefully received.

The Belfry on Dartmouth Hail

. NOTE : Mr. Kelly has already made one visit to the Indian Reservation at St. Francis in Canada and will write of his impressions in a future number of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. —Editor.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe more one considers

August 1924 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorCOMMENCEMENT 1924

August 1924 -

Article

ArticleRECIPIENTS OF HONORARY DEGREES

August 1924 -

Article

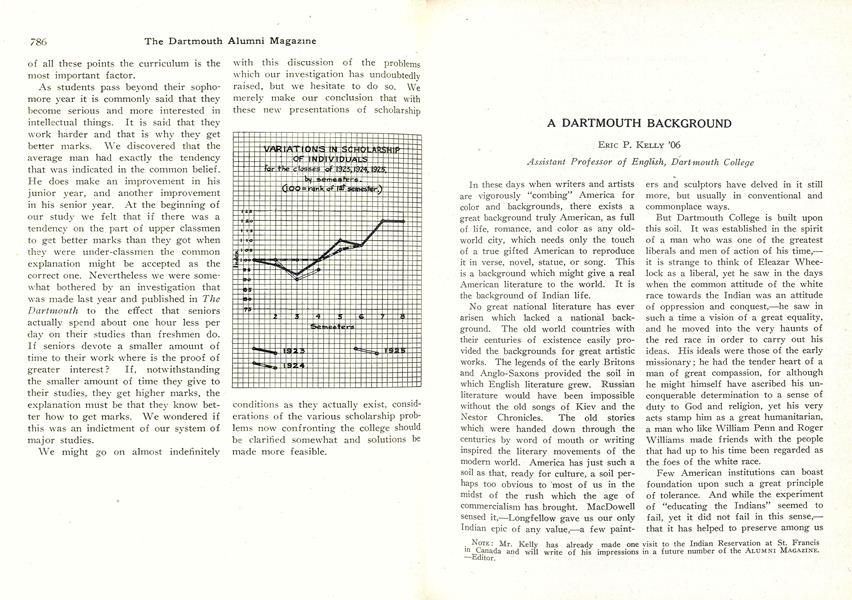

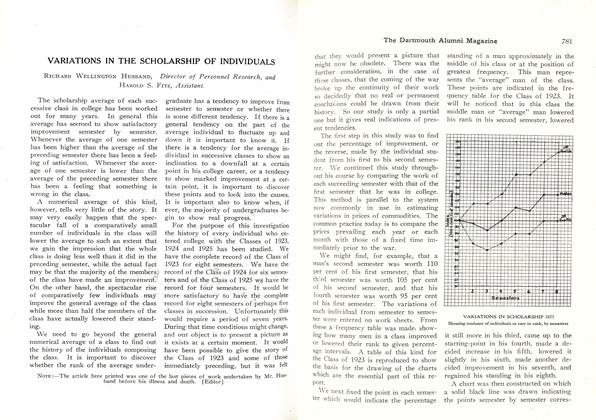

ArticleVARIATIONS IN THE SCHOLARSHIP OF INDIVIDUALS

August 1924 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

August 1924 By Perley E. Whelden -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

August 1924 By Perley E. Whelden

Eric P. Kelly '06

-

Article

ArticleVOX CLAMANTIS IN DESERTO

December 1924 By Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Article

ArticleSquash Little '91 "Constant Champion"

October 1936 By ERIC P. KELLY '06 -

Article

ArticleAn Important and Unusual Career

February 1938 By ERIC P. KELLY '06 -

Article

ArticleExacting Requirements in Science

January 1940 By ERIC P. KELLY '06 -

Books

BooksTHE STOLEN SPRUCE.

October 1952 By Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Books

BooksTHE CRYSTAL YEARS

January 1953 By Eric P. Kelly '06