Former Admissions Officer, Now on the DCAC's Side, Discusses the Old Question Of the "Well-Rounded" Boy

MOST people jump from the frying pan into the fire. I have just jumped from the fire into the frying pan.

Fortunately for me, and doubtless for everyone else, full responsibility for the administration of these two hot spots of contention, namely admissions and athletics, has rested, and still rests, on shoulders far broader figuratively, if not literally, than mine.

However, since I have had the unique experience at Dartmouth, in modern times at any rate, of having been associated with athletics, then admissions, and now athletics again—as closely approximating Eddie Jeremiah's dream of being at once coach of hockey, director of admissions, and chairman of the financial aid committee as will likely be possible so long as Dartmouth does not go the way of weak educational flesh and fall from the ranks of dignified educational institutions—the editors of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE have asked me for my personal and unofficial estimate of the admissions situation, particularly with reference to the athlete as one obvious example of the "all-around" boy who figures so prominently in alumni discussion of admissions.

As an omen of things to come in connection with my athletic duties, one of the first observations of a friend on learning of my new job was that, while he had been most reluctant to ask for the admission of a candidate as a personal favor, he certainly would have no hesitation in asking me for 50-yard-line seats at all football games.

Another was that the athletic situation should pick up now, because if anyone should know how to get an athlete past the admissions committee, it ought to be me.

To the former, I should like to say that I have more relatives than classmates, which uses up the 50-yard-line tickets. To the latter, I should like to say that if I knew a secret formula for admission, I should reserve it for my own son, 1 c vears away.

But the basic answer to both problems is the same. There simply are not enough 50-yard-line seats or spaces in the entering class to satisfy all who want them.

The ticket solution, though never completely satisfactory to everyone, can at least be solved by a formula giving preference to undergraduates and to classes coming up for reunions, which means that every five years or so, alumni get reasonably good seats.

The admissions situation, on the other hand, as you well know, is much more complex, and the number of happy peti- tioners is small compared to the number who have to be disappointed each year.

As I tacked the pictures on the walls of my new DCAC office and threw away stuff which had accumulated in my old desk in the "Ad" building, I could not help wondering whether my new duties would mean a change in personal perspective re- garding the admissions policies and prac- tices with which I have so long been fa- miliar.

For now, a new hand would feed me, and for the first time since my association with Dartmouth College I conceivably had an axe to grind with the admissions people.

I should naturally like to see the athletic teams at Dartmouth prosper. Assurance for this, aside from the best possible coaching available, would be a steady stream of super athletes matriculating each year. Would I now want to see the admissions office give preferential treatment to athletes?

I could not answer this question easily.

I have been aware of the great—often fanatical—interest among alumni in the athletic situation and of the dissatisfaction of some with what they have assumed is an admissions policy prejudiced against athletes.

But all alumni are not vitally interested in Dartmouth athletics. Some have even been dissatisfied on the assumption that the admissions office favored athletes.

Not so long ago two alumni fathers of the same class, whose sons unfortunately did not make the grade, wrote to the admissions office in disappointment. Their letters arrived the same day.

One of the fathers, whose son was a good athlete, accused the College of having turned his boy down just because he had manhood enough to be captain of football, center on the basketball team, a .400 hitter in baseball, and a good weight man in track. He strongly felt the admissions office should understand that a man with so many outside activities could not obtain grades as high as those of other boys in the same school who were selected.

The other father thought the College had sold out to the DC AO completely because the one boy from his son's school who had been accepted that year was a promising football player, whereas his son, who was not an athlete, had not been accepted.

The criticisms and doubts of these two fathers are typical of the contradictory criticisms to which the admissions system is most often subjected. Most criticism of admissions policy hinges on individual cases where the whole admissions policy is judged from single experiences—and almost inevitably on the basis of incomplete information both as to the individual case and especially the total competitive picture in which that case must be considered and decided.

Regardless of the fallacy of arguing from the specific to the general (fallacious if I recall correctly the lessons of freshman logic), the point at issue is whether the College is, or should be, prejudiced for or against any particular phase of a candidate's development, and if so, what.

I must answer this question as fairly as possible, before I can say whether I want the admissions office to lend assistance to the athletic department by showing special preference for athletes.

Before we look at the problem, though, I might incidentally point out that it is not always possible to determine a good athletic prospect.

I recall hearing of one instance in particular when this was proven.

Back when the Selective Process was first put into operation, and before other colleges and universities adopted similar systems, and when there was still considerable comment on the Dartmouth "experiment," a particularly outstanding fullback prospect was turned down.

The boy was accepted at another Ivy League college. Much bitter comment passed back and forth between his Dartmouth sponsors and the College.

A couple of years later Dartmouth won the game with that other college, and Mr. Hopkins, who knew the opposing coach pretty well, called upon him after the game.

During their conversation, the coach asked Mr. Hopkins if Dartmouth ever turned down anybody who might be accepted for admission at the coach's institution.

Mr. Hopkins allowed that this happened occasionally.

"I was given to understand not, but that the reverse happened frequently," said the coach.

"It happens both ways," said Mr. Hopkins.

"I really want to know," said the coach, "if you people turned down our fullback two years ago."

"I'm afraid we did," answered Mr. Hop kins.

"Well, don't tell anyone I said so," the coach whispered, "but between you and me, I think you have the better system."

If we are going to decide whether or not the College should give preference to any particular factor of a boy's development, we must first see what these factors are. In order to do this, we need a little background.

The present selective process of admission was born from the desire that Dartmouth should better fulfill its educational mission—l refer you to the words of Presidents Tucker, Hopkins, and Dickey as to what this mission is—and its form was shaped by the emergence of the modern socio-psychological concept that man develops not as a mind apart from body and soul, but as a whole, complex, but nevertheless integrated being. The process of "selection" became urgently necessary when over 25 years ago, more good men wanted to come to Dartmouth than could be accommodated.

If we are to select men with the strongest promise available for fulfillment of Dartmouth's educational objectives, a "competitive" basis of selection is inevitable.

There are those who question the validity of a "competitive" system. What their alternatives are I do not know. It is almost impossible to imagine any system which selects the few from the many which is not "competitive" on some basis, that basis being influential parentage, color of hair, geographical residence or what have you. Even patronage is competitive for those who seek it.

I believe, though, that these people fundamentally do not question the "competitive" nature of the selection of stu dents, but rather, they question the bases for determining the winners. So we come back to the beginning of the circle again.

What kind of men are best suited for Dartmouth's opportunities? Should the admissions office be especially benevolent to any particular type?

It would be very simple for the admissions officer (when I speak hereafter of the "admissions officer" I mean the term to include all persons and committees who are concerned with admissions) and infinitely easier on the wear and tear of his nervous system, if the College were to revert to admission solely by examination. Who could argue with him when confronted with an examination score whidi was below the chop line?

Unfortunately no one yet has devised an examination which can measure completely all the things which experience and research have shown to be important in the development of an individual and in predicting success in college. In fact, educators and others are hard put to agree on what success in college means.

The most easily accessible yardstick for measuring success in college is the aca- demic grade; and inadequacies of grading systems notwithstanding, no better mea- sure of intellectual accomplishment has been discovered.

Not everyone agrees that intellectual accomplishment should be weighted as heavily as it appears to be in the aims of the College and in the qualifications for admission. But those who would mini- mize the value of intellectual capacity and accomplishment are not facing the facts of history, for it seems to me that the great- est educational institutions of the world, the institutions which have survived the longest and have produced the greatest men, have been institutions which have been concerned primarily with the de- velopment of intellectual pursuits.

Educators, psychologists, and ordinary citizens who recognize the need for wis- dom have long known, however, that in- tellectual capacity and accomplishment alone do not make the world go round.

In short, we need to produce more "well rounded" men, and if Dartmouth is to produce her share, and more than her share, of men with "well rounded" capa- cities for leadership in community and world affairs, it is the job of the admis- sions officer to select from the available candidates men who appear best to possess these "well rounded" capacities, latent though they may be.

How can he, and how does he do it?

He can measure intellectual capacities with reasonable accuracy from tests and other data. He can determine the degree to which men have learned how to use these capacities from the record of their everyday performance in secondary school. He can discern their relative grasp of fundamental skills such as reading, writ- ing, speaking and understanding their na- tive language. He can determine, with less accuracy, whether the candidates' spe- cial aptitudes are too limited or special- ized for liberal arts. He can determine whether the candidate is capable of meet- ing, and is ready to meet, special require- ments in the .college curriculum.

(For more precise information concern- ing the mechanics involved in the collec- tion of these data, and concerning essen- tial and specific patterns of subject prep- aration, I refer you to the inclusive ar- ticle, Enter ye in by the Narrow Gate written by A 1 Dickerson in the October issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE last year. It's all there.)

After the admissions officer has determined the clearly intellectually incompetent and scholastically unprepared candidates, and after he has established the relative intellectual promise of those candidates who remain, his problem becomes twofold.

First, he must determine the degree to which these intellectually desirable men possess the other qualities which he knows are so vitally important. Second, he must weigh these,- one against the other, in order to select the best.

Positive determination of such factors as capacity for leadership, personality, social adaptability, breadth of interest, force, motivation, fortitude, perseverance, emotional stability, character, judgment, is a difficult problem. There are no wholly adequate tests. The admissions officer must judge these things from subjective observations of people who know the candi- dates, and from the candidate's activities.

The assumption is that the boy of intellectual promise who has had the interest to do well scholastically in secondary school, and in addition has had the zip to get into things which are naturally attractive to normal adolescents—athletics, clubs, and other activities—is a boy with stronger latent capacities for dynamic citizenship than one with more sedentary habits; and that the boy who pursues one or more of these activities to outstanding achievement or who exerts leadership among his contemporaries in school or community, possesses the latent force, purpose, personality and fortitude so needed in the leaders of the future.

Now comes the difficult part of the admissions officer's job. Not every boy can have an Intelligence Quotient of 150 (100 is average), be valedictorian and president of his class, captain of football, editor-inchief of the school paper, leader of the band, Junior Boy Scout master, and representative of the school at "Boy's State."

Each group of applicants includes a few with those very qualifications and runs the gamut down to candidates with very low I.Q.'s who have never done anything and who stand at the very bottom of their classes academically. The majority of the candidates, however, possess one or more of the desirable qualifications in varying degrees.

At long last, and how very long it must have seemed to you, we arrive back at the original questions: What specific qualifications of all those which we have mentioned as important should be given the most weight? Should the admissions office give preference to any particular group?

It is here that various schools of thought among Dartmouth men produce conflicting interests; and try though it may to be objective, each faction thinks that values which concern it should get a slight edge when selections are made.

Members of the faculty think the admissions office turns away hundreds of boys with intellectual promise superior to those whom they see in class, particularly the ones who fail. (Yes, inevitably boys fail, but I defy anyone to go through the files of the admissions office in the spring and predict specifically the boys who are destined for academic separation from college. The admissions office can tell about how many failures there will be, but not precisely who will fail.)

Coaches feel that the admissions office could have given a break to more boys with strong backs. The music director feels that the fiddle player who did not get in would have been more valuable to the orchestra than the one who did, and he is certain that the admissions office slipped badly. The alumnus whose son, or whose friend's son, did not make it, feels that something is wrong with the emphasis which the admissions office is placing on whatever it was that prevented the legacy from getting in.

And even admissions officers, from time •to time upon seeing a complete miscast floating around the campus, apparently devoid of brains, character and personality, wonder what is the matter with the system.

The admissions officer tries, however, to select the men who possess the most and the strongest of the various attributes which are important and desirable.

Since intellectual promise is fundamentally essential, and I think clearly the most important single item, the men at the very top intellectually are given first preference provided there is no evidence of moral degeneracy or emotional complexes. If they have other attributes, so much the better, but if not, there is need for men of sheer brilliance in the world, and Dartmouth is well equipped to help them.

(To the faculty who think we do not get enough of this type, I can only say that the admissions office usually takes all it can get, and to the alumnus who fears that we get too many, I can only say that even if there were more "geniuses" applying, there aren't enough of them in the country to cause any real harm or to cause serious restrictions for men of more nearly average capacities.)

The admissions officer next turns to men of lesser, but nearly equivalent, brain power and highly developed extracurricular accomplishment and personal development. Then he proceeds to the men of similar intellectual promise, but lesser developed personal qualifications; thence to men o£ like intellect but limited personal development. He then turns to the next level of intellectual promise and allround development, and so on, until he works down across the class in echelon, and until he reaches the last few spaces.

This is the borderline area. After the cream has been skimmed from the topand any number of people from any number of vested-interest groups would probably agree upon the first four or five hundred men selected—the number of men who are still in the running is simply terrific in comparison to the number of spaces left. You will remember that those who have scholastic aptitudes and preparation which are clearly inadequate have been eliminated. Thus, those who are left are boys with slight differences in their scholastic backgrounds and with an infinite variety of personal qualifications. It is here that minor deficiencies in scholastic backgrounds or lack of positive personal development are enough to eliminate a man from the competition, and it should be quite obvious that a man with "all-round" extra-curricular interests but who is short on the academic side has no place in the competition. It would be no favor to such a man to let him in, for the competition which he faces in connection with admission will continue, and even accelerate, in the academic pace set by his classmates in college.

Until this point in the competition is reached I personally could not argue that athletes who were not relatively equal to other candidates in all respects, be given a place, in the class. But from this great mass of boys whose intellectual promise is almost indistinguishable one from the other, I should be willing to argue that, if among them were individuals who had developed any one characteristic or activity to a marked degree, be it running with a football, composing and publishing music, or trapping for spending money, they be given some preference. And this is the way it works out in practice, except for two special considerations.

In recognition of the stake which the alumni have in the College, and in recognition of positive benefits which accrue from continuity of bloodlines down through the classes, where candidates of otherwise equal or nearly equal qualifications are being considered, preference is given first to sons of alumni.

In reassurance of the fact that the College continues to be interested in Dartmouth sons, I give you these figures:

In the classes 1925-1930, inclusive, the average entering class was 617, of whom an average of 33 (5-5%) were Dartmouth sons. The classes of 1931-1935 averaged 648; 44 Dartmouth sons (6.8%). In the classes 1936-1940, averaging 667, the average number of Dartmouth sons was 66, (10%). An average of 686 men comprised the classes of 1941-1945 with an average of 93 sons in each (13.5%). The class of 1945 included 109 Dartmouth sons for an all-time pre-war high.

During the war the figures were distorted by the general confusion. But the first normal postwar class, 1951, totaling 671 men, had 139 sons (20.4%). The figures for the class of 1952 will not be available until that class has matriculated.

That the committee on admissions is still bending over backwards in favor of Dartmouth sons, perhaps beyond the point of the best interests of some, is clear when we find that the academic mortality Dartmouth sons has been substantially greater than that of other students.

The second special consideration is in recognition of the value o£ men from all parts of the nation joining together in common pursuit of knowledge and understanding. For this reason, men from re- mote sections, namely the far west and deep south, are given preference over men of otherwise relatively equal potentialities.

But you know all this, and I still haven't answered my question to myself as to whether my own vested interest has changed my perspective of the over-all admissions situation.

The answer is no.

We all recognize that athletics are valuable to those who participate in them, and to the college as a rallying point for loyalties, as a recreation for spectators, and as a common ground for many alumni. But athletics lose their value if individuals are exploited because of them, or if their significance is distorted. This goes for all extra-curricular activities.

I want to see Dartmouth have winning teams as well as the next most rabid fan, and I am not naive enough to expect in these days of competition for athletes among colleges, days of hyper-enthusiasm and distortion of the values of athletics on the secondary school level also, that good athletes who are under considerable pressures will naturally gravitate toward Dartmouth.

I believe there are many good athletes of sound intellectual promise, of worthy character and other desirable traits, some of whom are being attracted to institutions of less sound purpose than Dartmouth's, who will come to Dartmouth if they can be shown what the College has to offer and can be enlightened as to what really counts. I want good athletes to become interested in Dartmouth and to be accepted. But I do not want to see the policies of admissions which have been so carefully established over the years compromised in order to do it.

There is one other point I should like to make.

The natural inclination of anyone who is strongly behind boys who are not accepted, as we have seen in some of the above instances, is to judge the College and its admissions policy on those boys. Since in many cases these boys have had strong personal qualifications and good scholastic records, and because in most instances the basic reasons for their not having been accepted is their failure to measure up competitively to the scholastic qualifications of the boys who did get in (their personal qualifications being relatively equal), the inference is that the College is filling up with a lot of "longhaired brains" who will earn Phi Beta Kappa keys but will not be able to lift them.

Let us look for a moment at the boys who do get in instead of at those who do not.

Intellectual promise? Yes. The highest intelligence averages of all entering classes in Dartmouth history came in with the class of 1951. (I use this class because the scores for the class of 1952 are not yet available.) Scholastic accomplishment? Yes. Over 80% of the men accepted in the class of 1952 were in the upper quarter of their respective high school classes; over 40% were in the upper tenth.

How about their "well-roundedness"?

We can't definitively measure the real factors which I have tried to show are the significant factors in the term "well rounded," but insofar as activities show them, we get a clue from the activities of the class of 1951.

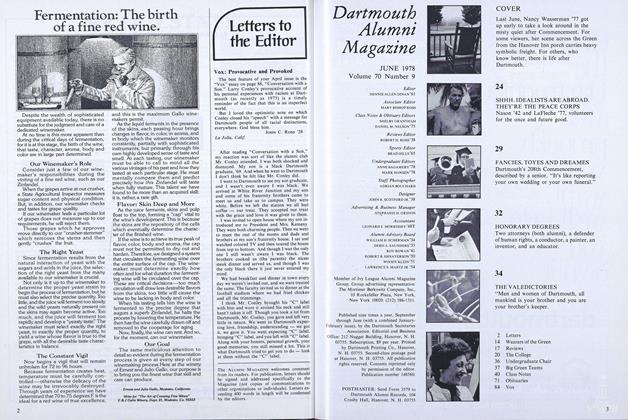

There were 218 football lettermen, including 31 captains, matriculating in that class. The '51 freshman team defeated Harvard, Boston College, Yale, tied Army, and lost to Boston University freshmen. A total of 113 '5 I's played baseball in secondary schools; 14 of them were captains. The team won 5 and lost x. In addition: 130 basketball players, 10 captains; 40 hockey players, 3 captains; 10 lacrosse players, 20 skiers, 35 soccer players, 55 swimmers, 46 tennis players, and 114 track participants came in with the class. Some of this is, of course, duplication, for many of these were participants in two or more sports. The '51 hockey team won 7, tied a, lost 1. The lacrosse team split 3 and 3. The swimming team was undefeated in six meets.

This does not indicate that Dartmouth will be invincible on the varsity fields next year. There is a big jump from freshman to varsity competition. But it does show that not all the men who were admitted to the College were just "brains."

In addition to athletic accomplishment in the class of 1951 there were 100 class presidents, 37 presidents of student councils, 30 editors-in-chief of school publications, and men of a variety of other interests.

The class of 195 a will in all probability be as good scholastically and as "well rounded" as the Class of 1951.

If you still think the College is filled with nothing but anemic intellectuals, a visit to Hanover to see for yourself is recommended.

You'll find the boys playing touch football on the campus as well as on the DCAC playing fields as they always have. You'll find them skiing on the slopes of Oak Hill. You'll see a couple of hundred of them slamming around Moosilauke before college opens. You'll find them hunting and fishing, and on the golf links.

You'll find them yelling at the movies and sleeping in the Tower Room. You'll find them playing bridge and some of them drinking beer. You'll find their interest in the fair sex is no different from yours (and mine) at their age.

And you'll find them studying, questioning, and hoping that they can find the answers to problems which your generation and mine have thus far royally fouled up, and which they may have to try to pull out of the fire with their lives, even as their predecessors did in 1914 and 1941. Come up and take a look.

I have purposely left personalities out of this discussion. But I must mention that I have been fortunate, indeed, to have had the privilege of working first with Bob Strong, and later with A 1 Dickerson in the'most trying of times.

My personal respect for both these men cannot be described.

I do know, however, that had either of them been less mindful of the primary purpose of Dartmouth College, or short of integrity, or unwilling to sacrifice his leisure far out of ordinary expectations, had either of them been less persistent and eager to pursue ways and means of improving the administration of his duties, or humanly frail enough to let frequent unfair attacks on his personal competence weaken his steadfastness, I can attest to the fact that right now the whole Dartmouth family would have been wracked in acute dissension, perhaps to the point of disintegration.

Admissions is the heart of Dartmouth, and any wavering from sound and tenable admissions practices could break that heart.

ASSISTANT ATHLETIC DIRECTOR: Edward T. Chamberlain Jr. y36, author of this article, has re- turned to familiar haunts on Memorial Field. He was assistant varsity football coach under Earl Blaik for four years while heiping the late Dean Bob Strong with freshman and admissions work.

AN UPSURGE IN INTRAMURAL DORMITORY SPORTS followed the arrival of the spirited freshman class last fall, indicating the all-around interests of the scholastically capable classes now being admitted.

THE DCAC WILL SETTLE FOR A DUPLICATE THIS FALL: Stiff competition for admission hasn't produced a drop in football caliber. The '5l eleven above was one of the best yearling teams in recent history.

'5l SHINES IN THE RING TOO: Among the three freshmen who won College boxing titles last year was Charlie Ryan (right) who defeated his class- mate/ Ray Mullin '5l, in the 145-lb. class finals.

OOME TIME AGO President Dickey remarked, not O entirely in jest, that if he ever had to wear an albatross around his neck, the words "well rounded" would probably be inscribed on its breast. He was thinking of the hopeful claim made for practically every one of the thousands of applicants for admission to Dartmouth. The editors, with an October article on admis- sions already in mind, recognized the President's remark as an interesting approach to the whole general problem. And when Eddie Chamberlain recently left his job as Assistant Director of Ad- missions to become Assistant Director of Ath- letics, they realized that they had the ideal man to write their admissions article and to discuss the "well-rounded" applicant as exemplified by the athlete in whom he now has a special interest. The result is the extremely readable article which the MAGAZINE is pleased to present here. Although "personal and unofficial," it is as in- formed as anything that could be written in Han- over today.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

October 1948 By DONALD G. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD, ROBERT P. BURROUGHS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

October 1948 By E. PAUL VENNEMAN, HERBERT F. DARLINC, ROBERT M. STOPFORD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

October 1948 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912

October 1948 By HENRY K. URION, RALPH D. PETTINGELL, HENRY B. VAN DYNE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

October 1948 By SIDNEY C. CRAWFORD, CHANDLER H. FOSTER