President Dickey's address at the Convocation Exercises opening Dartmouth's 180th year was delivered Friday morning,October i, before a student-faculty audience that filled Webster Hall to overflowing. It marked a departure from the short,informal talk with which President Dickeyhas opened each college year since takingoffice, and dealt with national affairs aswell as with the educational purposes ofthe College. The address follows in full:

MEN OF THE COLLEGE:

FOR EACH OF US HERE, this day symbolizes our coming together for the common purpose, and the sole purpose, of advancing each of you a little further in the direction of being a liberally educated man. Whether you have one or four years of Dartmouth remaining, it is worth while, I think, to ponder the fact that after you leave here you will never again enjoy the experience of having even one other person, let alone an entire institution, dedicated exclusively to the job of working with you to make you a more worthy and a more effective human personality.

For many of you there are graduate and professional schools ahead, but there the purpose is different. They will be concerned, and right rigorously too, with making you a more highly trained man or a more scholarly man. Whether or not you are to enjoy the privileges of such advanced training will in large measure be settled here, but that is not why Dartmouth exists. And even though you do not go on to advanced study, the manner in which and probably the extent to which you will later earn a living may well largely be determined here. But that also is not why Dartmouth exists. Nor, incidentally, does Dartmouth exist to satisfy the social appetite of men who simply do not know what else to do with themselves. And yet the College is interested in fostering healthy social appetites in her men.

It is no easy business, gentlemen, to tell you why Dartmouth exists. Literally millions of words have spilled over in the constant stream of telling which has accompanied the rise of the liberal arts college in America. Even if I were able to distill it down to a few clear words, I still could not give it to you. I still could not tell you in any real sense the "why" of Dartmouth. You may well ask, "How is it that it cannot be said?" I can give two reasons, and both of them are of prime importance to you in the business which lies ahead of us this year. First, I probably could say the right words just as the right words about many other things have been said by one man to another for thousands and thousands of years and yet men still have so little understanding in common about those things. It is only as we approach the common ground of like experience that we are able to communicate, let alone commune, with each other. Words are the indispensable, even if faulty, symbols of our experiences, but in the most basic sense they are not and they cannot be a substitute for experience itself. The fact is that words impart no immediate and true meaning unless they are spoken between those who have shared substantially a common experience. In that truth, which is both very simple and vastly complex, lies the secret, I believe, of that mutual understanding and forbearance which you and I can realistically seek as between races, religions, classes and nations as this generation's contribution to the quality of progress in our time.

The second reason comes even closer to home for you. And it is this: there is a special uniqueness in the Dartmouth experience. A man may well have an understanding of other liberal arts institutions and still not know the character of this College. For myself I doubt that a man can ever know it well until he has lived it the year around more times than once or even twice. There is a simple importance of place, some call it "place loyalty," which attaches to everything that is Dartmouth. That loyalty, like most loyalties, has its provincial aspect, but also like most true loyalties it gives that peculiar quality of strength which lies close to the heart of a good man and a great institution.

A year ago on this same occasion I suggested that an introduction to humility was a large part of any man's education. May I today suggest to you that an introduction to loyalty is also a large part of any man's education. Humility is an indispensable prerequisite to learning and wisdom. Loyalty is the temper in the steel of the true man; it is an essential ingredient of effectiveness in the affairs of men. And there is no better time than now and no better place than here for each of us to introduce himself to these two qualities of the truly educated man.

Like humility, the appearance of loyalty is often easy and almost as often it is in some degree false. Loyalty, however, is a more complicated, a more puzzling, a more difficult and almost certainly a more dangerous quality than that of humility. Humility is a passive quality in a man; loyalty on the other hand, is a positive, sometimes almost assertive thing. Loyalty is that quality in a man which carries the bond of human solidarity beyond the reaches of knowledge and belief, indeed even beyond the normal bounds of faith itself because faith rests on the assumption that all must be well however incomplete or imperfect the proof of the moment. Loyalty, as I have said, goes beyond that; it is based on no such comfortable assumption; to the contrary, true loyalty only comes into play under less favorable circumstances when all is not or may not be well. Here, I believe, is both the meaning and the difficulty of the business. Loyalty is not merely an ethical concept, nor will the real thing be found in the marsh lands of sloppy sentimentality where unfortunately it is most often sought. There are many aspects of the real thing, but this morning I want to bring out one aspect which it seems to me has remained rather obscure. You might call it the practical or the functional role of loyalty in human affairs. Perhaps I can make my thought concrete by going back to my statement that "True loyalty only comes into play . . . when all is not or may not be well." The key word is that three-letter word: "all." No man and no institution is without flaw in all respects and at all times. Every human being and every human institution constantly needs that spoken or unspoken support which in the face of trouble or indiscriminate criticism answers with the words "Perhaps, but . . or "Yes, but . . ." More often than not the daily work of loyalty is performed by the perceptive man who responds either to himself or to another critic: "Yes, it may be, and if so it's too bad, but there's a lot more than just that to my friend, or my college or my country."

In a world of gods and perfect institutions (not to mention here the complicating factor of goddesses) there would be no need for the quality of loyalty. But here on earth loyalty is truly the protective lubricant of our human and imperfect world. Without it friendships would quickly wear thin and the daily work of the world would grind to a most unpleasant stop in every human institution, including, gentlemen, Dartmouth College.

Loyalty is essential, yes, to help us over the rough spots of human faults and differences in every mortal mechanism, be it the family, the College, a business or the nation, but if misunderstood and misapplied it can itself become an embarrassment and hindrance to better human relations and progress. It would be fatuous and false to deny that every loyalty carries with it a risk and some measure of responsibility. The risk is that one may be wrong in believing that, all things considered, loyalty is still due a particular person or institution. Misplaced loyalty makes heavy tragedy. The responsibility is twofold: first, to try to be right in giving one's loyalty, and secondly, to do one's full share within the circle of one's loyalty to remedy genuinely reparable faults and flaws. I do believe that the measure of a man's wisdom and character is largely to be found in the way he meets that risk and those responsibilities. Manifestly, there are no pat answers to be given you. But, gentlemen, this is where the stuff of a Dartmouth liberal arts experience ought to make a difference. The inescapable and torturingly difficult decisions of loyalty can only be well taken by a man who has acquired a sense of proportion as to values. If you should leave here without a heightened sense of proportion, it would be better that you and Dartmouth never met.

It would be pretentious and futile for us on this occasion to attempt any very extensive probing of the application of loyalties. But I should like to say this much more. As I assume each of you realizes, the subject of political loyalties is far from academic today either in this country or elsewhere. Some countries have had what might loosely be termed a conspiratorial tradition in their national life and in those countries men have become all too accustomed to trading the appearance of loyalty to the highest bidder among the conspirators seeking political power. It is not improbable, I think, that many of those countries were easy conquests of international communism in some measure just because local history paved the way with respectability for the conspiratorial approach to politics and government.

On the other hand, in the Anglo-American countries we have been free for some centuries now of any such conspiratorial tradition in our approach to government. We have had our episodes, yes, but they are notable because they have been exceptional. And yet today the Anglo-American world along with much of the rest of the world outside the Soviet orbit is faced with the problem of how to deal with the effort of international communism to introduce or to exploit the conspiratorial approach to government within our respective national lives.

Many of our most thoughtful citizens are disturbed by both sides of the problem. On the one hand many good and true Americans have felt that little good could come out of investigations into un-American activities which too often seem to be conducted without even rudimentary regard for traditional Anglo-Saxon standards of dignified judicial and legislative behavior, not to speak of our most elementary notions of fair play. On the other hand many of us do not see how this democracy can avoid the responsibilities of simple self-defense against the intrusion of conspiratorial methods in our internal affairs.

It seems to me that those measures of self-defense cannot stop short of public exposure of established conspiracy and of requiring unquestioned political loyaltyin the sense of loyalty to country—from those who of their free choice accept the responsibility of serving this nation as employees. The late Justice Holmes once said that "men must turn square corners when they deal with the Government." Certainly the corner can be turned no less squarely by those who serve the Government.

Leaving aside the large question of method in these matters, I suggest that there are two twin devils of substance at the heart of the problem. One of these devils is the attitude which seeks to brand as disloyal any and all who are or who have been critical of some aspects of American life. The other devil is the attitude within a man which leads him to the verge of disloyalty or actually into it simply because all things at all times are not perfect in all of America.

Gentlemen, I have taken the liberty of talking about these things with you this morning not just because the subject of loyalty has an aspect of current public significance, but rather because it is important to you as you live your life here at Dartmouth in the year or years ahead. Your capacity for loyalty later is in your hands today. The demands of tomorrow on your loyalty may be heavier than any one of us even dares to fear. If I may be permitted one word of advice to you, it would be: do not be ashamed of even the provincial aspects of the familiar loyalties which have served good men well for a long, long time, but rather seek to understand and use those loyalties to build the larger loyalties at the core of which rests respect both for truth and that brotherhood of man within which one good man found all the freedom, goodness and peace we everlastingly seek for men on earth.

And now, Men of Dartmouth, as I have said to some of you before, as members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such.

Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be.

Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you.

We'll be with you all the way and "Good Luck!"

PROFESSOR RUSSELL B. THOMAS of the University of Chicago has been appointed Visiting Professor of the Humanities for the first semester. He is helping to teach the special humanities course Classics of European Literature and Thought, which was introduced two years ago as an interdepartmental offering.

Donald Bartlett '24, Professor of Biography, is serving as chairman of Humanities 11-12 this year, and others teaching the special course are W. Stuart Messer, Daniel Webster Professor of the Latin Language and Literature, and Royal C. Nemiah, Lawrence Professor of the Greek Language and Literature.

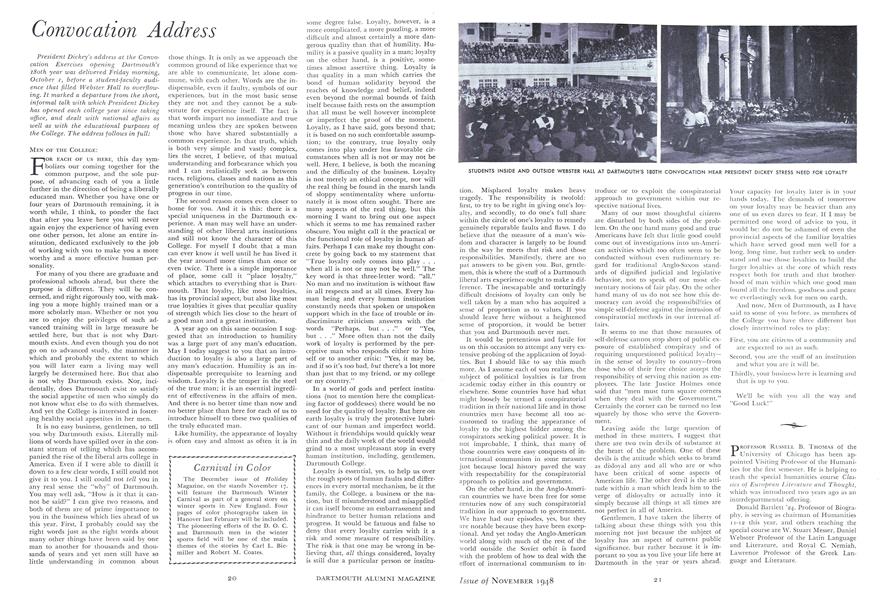

STUDENTS INSIDE AND OUTSIDE WEBSTER HALL AT DARTMOUTH'S 180TH CONVOCATION HEAR PRESIDENT DICKEY STRESS NEED FOR LOYALTY

Carnival in Color The December issue of Holiday Magazine, on the stands November 17, will feature the Dartmouth Winter Carnival as part of a general story on winter sports in JN[ew England. Four pages of color photographs taken in Hanover last February will be included. The pioneering efforts of the D. O. C. and Dartmouth men in the winter sports field will be one of the main themes of the stories by Carl L. Biemiller and Robert M. Coates.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCIVIL RIGHTS IN AMERICA

November 1948 By ROBERT K. CARR '29, -

Article

ArticleA Report from Europe

November 1948 By EDWIN A. BOCK '43 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924

November 1948 By JAMES T. WHITE, RICHARD A. HENRY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

November 1948 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, MORTON C. JAQUITH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912

November 1948 By HENRY K. URION, RALPH D. PETTINGELL