WITH characteristic clarity and vigor President Baxter has presented in the Atlantic the financial plight of Williams College today and by inference the worse situation of many another private college which has rendered notable service to the nation. As he points out, the prestige of such colleges is especially high because of their records in wartime. The convincing specific evidence he has given shows not only the money deficit but the threatening deficit in quality because of the present underpaid teachers. All who know of the long and distinguished history of Williams will be confident of success for President Baxter's current appeal for increased endowments to meet present debts and to provide a basis for a continuing high quality education. Yet one wonders if the extent of the need does not call for a somewhat different balance in sources of income for the coming years. Possibly there are other and better ways of financing college education in a world where values are often best seen when they are constantly asserted in comparison with other claims on our pocketbooks.

To be sure, the severity of the difficulty will somewhat abate when the G.I. students have graduated. But for some of the professors about to retire on pensions, the outlook is already indeed bleak and the past loss irreparable. They must attempt to live in their retirement on pensions paid for in forty years with dollar dollars and providing today dollars with fifty cents' purchasing value. Such "security" based on past investments is unlikely to attract young men of ability who desire not merely a minimum living salary, but some stable provision for themselves and families in their old age.

Whatever justifiable confidence President Baxter has in his campaign for greatly increased endowments, and however justified everyone must think his appeal, his solution for present ills and probable future needs seems somehow strangely unconvincing. Supposedly adequate endowments have been proved of decreasing help as rising costs have coincided with declining income. And the supply of rich and generous alumni is likely to be reduced under changing economic conditions.

Of the causes which have produced so disastrous a situation, most seem irremovable. Some degree of inflation is likely to continue unless our whole economic system collapses. The G.I. Bill of Rights has produced a burden which the colleges have nobly shouldered but which is back-breaking and inflicting serious and continued injury. The low bank rate, useful enough for selling government bonds, is, as President Baxter has said, equivalent to a capital levy on college investments, and government pressure on colleges to overwork their faculties gives little assurance that closer association with the central government will be beneficent. Watering the college stock by mass production methods destroys the very values the small colleges have habitually produced, and is unthinkable.

To meet economic requirements and at the same time to preserve essential values is a problem for which no other solution is proposed than larger endowments. Surtaxes reduce the largest incomes to a fifth or less of their face value. The loyal alumni of the old, and still relatively rich, private colleges will, we hope, once more respond to meet the critical needs of their alma maters. Will they also wish to meet losses incident to unsound procedure? A college must on its business side mirror conditions as they are, not as they were.

What are these conditions? Briefly, an amazing rise in union wages, a somewhat smaller but still considerable rise in business and professional salaries secured by higher prices, and an astonishing attempt by colleges to hold tuition fees near their level of a few years ago. President Baxter argues that in a crisis it is no more justifiable to raise college fees than to raise the price of milk. Up to date the price of milk has risen enough, as it should, to allow farmers to produce it. Similarly, the colleges must not low price themselves out of existence when people will pay for educational values as they will for others.

If the 1939 scales of income and outgo represented a kind of rough justice between a parent's ability to pay and the services rendered, clearly tuition charges should rise to match the average increased incomes of today. At a time when most other expenses have risen, why should the charge for tuition remain nearly static? It has been objected that to set fees in economic terms would make college education a luxury. But would it, if ability to pay has risen the country over? As for its effect on scholarship boys, the really ambitious have never feared to seek the best regardless of price.

Americans have shown themselves willing to make sacrifices for what they recognize as valuable. And who will believe that a college education is really worth the effort needed to secure it if the colleges tamely submit to a mere 18% rise in college teachers' salaries when the other costs of living have gone up 56%?

All college students are quite clearly the beneficiaries of endowments and other gifts. Why, though, should the average parent able to pay profit selfishly from the charity of underpaid and altruistic teachers? Raising the fees would largely cover present deficits and restore budgets to the proportions of 1939. New endowment could then be devoted almost entirely to scholarships and to adequate salaries.

Other ways of countering the blow of inflation are possible. The smaller number of large gifts must be met by widening the field of support through the annual alumni fund. If Dartmouth can raise over $300,000 yearly by such a fund, other colleges, if they will devote equally skilled attention to it, can vastly increase the necessary support. Moreover, like a community fund, an alumni fund enables loyal supporters to make small gifts regularly, although they would feel unable to contribute their total sum at any one time. A further dividend comes in the steady interest aroused by alert class agents and regular reports in alumni magazines. To raise $10,000,000 for investment purposes by a campaign would be less effective. A constant assertion of the valuable privileges provided by the college and determination to increase the quality will rouse a respect likely to be reflected in last wills and testaments. No one will accuse a college of running for profit if it enables its teachers to live with dignity and to teach unharried by financial fears. Getting more supporters and firmly increasing the quality of instruction is not promoting "narrowness" or "educational decay."

President Baxter's frank article does double duty by reminding us of colleges not only worthy, of their noble inheritance but also tenacious of their peculiarly American variety under freedom. As we are all coming to see, equality of opportunity does not mean identity of opportunity. To maintain variety perhaps we must also have varied methods to ensure the maintenance of privately supported colleges. We must sadly admit that far too often financial help from the public funds has been contaminating. And let us not forget as we supply the needs of these colleges the words Principal Saltonstall has used of a secondary school: "Exeter is not a private school. John Phillips founded the academy as a public school. It is 'private' only in the sense that it is not run by public officials, but Exeter predates the public school system. And it has never permitted wealth or family connections to be a qualification for admission."

This proud boast can be matched by many small colleges. Let us hope the example of the late Thomas W. Lamont will be followed by other men of wealth who know the value of hard work and inspiring teachers. The ruggedness and inventiveness shown in earlier crises will, at any rate, enable the colleges as inflation hits them to give a Roland for an Oliver.

Mr. Roberts' article represents an individual point of view but it raises such a fundamental question with regard to present-day financing of the private college that the editors are glad to accord it the editorial page. Mr. Roberts, now retired and living in Natick, Massachusetts, was formerly Senior Master and Head of the English Department of St. George's School,. Newport, R. 1., where he taught for forty-three years.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleStumps and Scholarships

April 1948 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

April 1948 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

April 1948 By WILLIAM H. HAM, WELD A. ROLLINS, MORTON C. TUTTLE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

April 1948 By A. W. LAUGHTON, WILLIAM H. SCHULDENFREI, ERNEST H. MOORE -

Class Notes

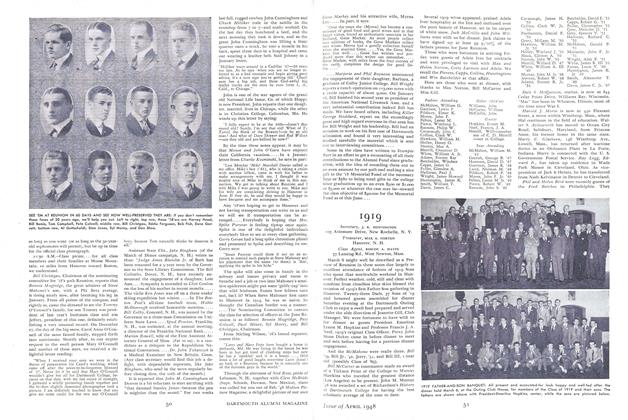

Class Notes1919

April 1948 By J. K. HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON, ROSCOE .A. HAYES