by Muzafer Sherif and HadleyCantril '28. John Wiley and Sons, 1947; pp•525; $6.00.

The very fact that work bearing the title of ego-involvement is a collaboration of two authors, each endemic to a different culture, shows that the positive values of the concept are not lost. Ego-involvement means more to the authors than one's own vested interests; it means as well the warm attitudes one holds as a member of a group, man's relation to the world around him, in addition to his private advantage.

The authors indicate that the development of the ego hinges first on man's conceptual (symbolic) capacity and secondly on his wide reciprocal social relationships. Thus, he learns attitudes which act as guides for his ego; he learns to perceive and judge situations in conformity with the standards, values and norms of the group with which he identifies and becomes ego-involved. Such perceptions may be erroneous. In this connection, the authors cite Adelbert Ames's experiments on visual illusions which point clearly to a continuity of our perception of immediate external situations and our perception of social relationships. The ego-involved attitudes, affectionately embraced and firmly defended, determine the way in which the world is interpreted, whether illusion or fact. For example, a southern white child learns to perceive and judge Negroes, not as they are, but as his group regards them; the attitude then takes form, hardens, and becomes ego-involved. By the same token, but in a more enlightened way, attitudes which are "socially important can and will become personally important, and what is personally important can and will be socially important." The modifiability of human nature, and the re-alignments of ego-involvements, the authors believe, offer promise for the resolution of conflicting values.

The authors summarize and classify the many evidences, experimental and observational, of ego-development and ego-involvement. Interesting examples of dissociation and "breakdowns of the ego" are also described; illustrations of ego-involvement are chosen from literature as revered as Euripides and Shakespeare, and as modern as Sinclair Lewis and John Steinbeck. The last chapter is a judicious critique of the psychoanalytic approach to ego-problems.

The presentation is erudite and imposingly documented (639 references). One wishes that the work were less technical and easier reading. The authors deal with widely significant social issues which deserve more general attention; a less forbidding style would invite more readers.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleStumps and Scholarships

April 1948 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

April 1948 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

April 1948 By WILLIAM H. HAM, WELD A. ROLLINS, MORTON C. TUTTLE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

April 1948 By A. W. LAUGHTON, WILLIAM H. SCHULDENFREI, ERNEST H. MOORE -

Class Notes

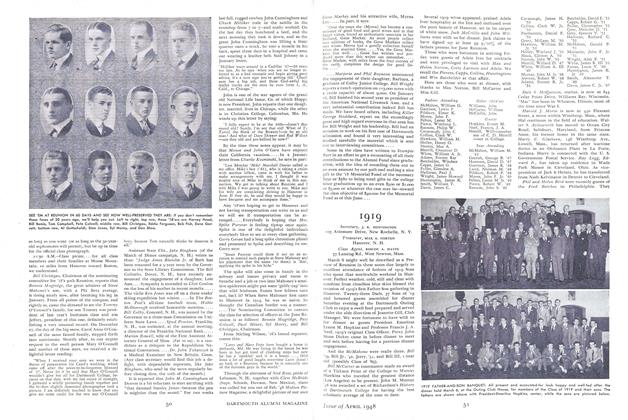

Class Notes1919

April 1948 By J. K. HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON, ROSCOE .A. HAYES

Books

-

Books

BooksWITNESS TO REVOLUTION: LETTERS FROM RUSSIA 1916-1919.

MAY 1972 By GEORGE KALBOUSS -

Books

BooksPERSPECTIVE IN FOREIGN POLICY

JANUARY 1967 By HENRY W. EHRMANN -

Books

Books"SUNNY INTERVALS." A BOOKMAN'S MISCELLANEA: LONDON/SAN FRANCISCO/HANOVER.

FEBRUARY 1973 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksMARRIAGE.

JUNE 1969 By LOUIS WOLF GOODMAN '64 -

Books

BooksSOCIAL FOUNDATIONS OF EDUCATION.

January 1956 By RALPH A. BURNS -

Books

BooksTHE LIBERALIZATION OF AMERICAN PROTESTANTISM: A CASE IN COMPLEX ORGANIZATIONS.

MAY 1973 By RONALD M. GREEN