On October 30, 1967, Martin Luther King and three other ministers flew from Atlanta to Birmingham, Alabama, to begin serving a five-day jail sentence for contempt of court. It was not the first time King had been jailed but the 19th. It was, however, to be the last; less than six months later he was shot dead.

The importance of the sentence lies in the fact that this time he had been ordered to jail not by southern judges or rural sheriffs, but by the Supreme Court of the United States, and that the charge was not trespassing or boycotting but disobeying an injunction. That conviction, its precedent, and its implications for the '70s, are the thrust of The Trial of Martin Luther King.

The injunction is an unusual weapon in the arsenal of jurisprudence. A court order to a person or persons directing them to do something or to refrain from doing something, it can be issued ex parte, without its subject having an opportunity to appear to show why the injunction should not be issued. Unlike traditional laws,- the segregation statutes, for instance - which, if violated and then shown through the appeals process to be un-Constitutional, carry no punishment, the trial of Dr. King showed that violation of an injunction, even when the injunction is eventually shown to be unlawful, can result in conviction and imprisonment.

An ex parte injunction may, of course, be appealed and overturned, a time-consuming process. Its purpose is to delay, and its use has tended to be to break the momentum of a mass action or to inhibit the publication of news, like the Pentagon Papers, while it is still "hot." In King's case, the injunction - an order forbidding parading without a permit - was issued just two days before Good Friday of 1963, which was the scheduled starting date for the Birmingham demonstrations that were to lead to passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The injunction ignored the fact, as did the Alabama court which convicted the defendents, that the demonstrations had been a year in planning and already twice postponed, that the symbolic values of demonstrations on Good Friday and Easter Sunday were crucial, and that the momentum built up could not have been halted without a fatal dissipation of the enthusiasm and discipline needed for a nonviolent mass demonstration. It also ignored the fact that King's people had, in obedience to local law, requested a permit from City Commissioner "Bull" Connor, only to be told, "No, you will not get a permit to . . . picket. I will picket you over to the City Jail." The Alabama court chose law and order, and the United States Supreme Court, by a five-to-four margin, followed suit.

What is noteworthy about this book, written by two law professors, is its ability to make clear the intricacy and delicacy of situations in which law and justice conflict, and the way in which the writers demonstrate their own beliefs both that law is the basis of all freedom and that American law is sometimes misused to abuse freedom.

Their feeling, explicitly stated, is that the "case was mishandled by the Supreme Court" and "is exerting a harmful effect on our social and political processes" by making it more difficult "to keep the moment of social debate and institutional change open in the society." Nevertheless, they give full weight to the opinions of those disagreeing, including some of the traditionally "liberal" elements of the media.

For the layman, the book also provides a fascinating inside look at the way in which the Supreme Court reaches its decisions: the hierarchy, the protocol, the shifting alignments of votes that determine what we call an "activist" or a "strict constructionist" court.

It is an enjoyable book, technical enough for a judicious look at the judiciary process, lively enough to give us a sense of the characters involved. Thus we have Bull Connor announcing, "We're not going to have white folks and nigras segregatin' together in this man's town," and another, then lesser-known, proponent of law and order denouncing "caterwauling, riot-inciting"-type Negroes with the words, "I donot communicate with lawbreakers." Unlike Connor, the last speaker had a future before him. His name was Spiro T. Agnew.

THE TRIAL OF MARTINLUTHER KING. By BarryMahoney '59 and Alan F. Westin.Thomas Y. Crowell, 1974. 342 pp.$7.95.

Dartmouth Professor of English, Mr. Walker,Chairman of Black Studies program, teachestwo courses in Black American Literature.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

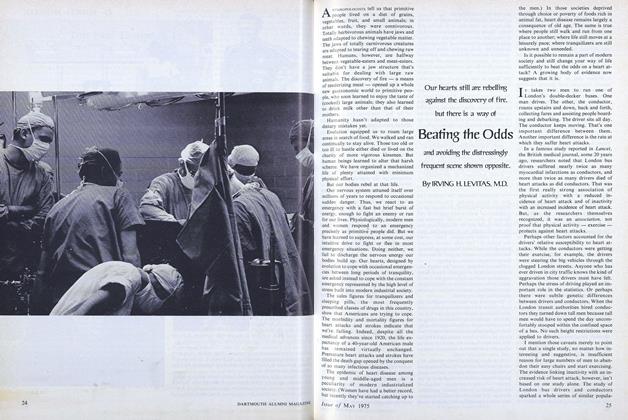

FeatureBeating the Odds

May 1975 By IRVING H. LEVITAS, M.D. -

Feature

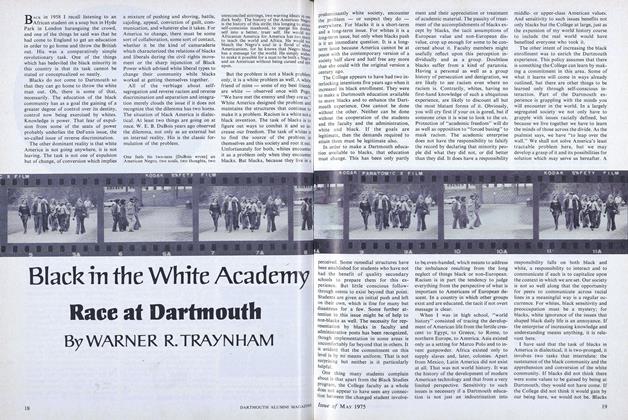

FeatureBlack in the White Academy

May 1975 By WARNER R.TRAYNHAM -

Feature

FeatureRalph Sterner: See-er

May 1975 By RALPH STEINER -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

May 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleWhere the Grass Looks Green

May 1975 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

May 1975 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR., HARTHON I. MUNSON

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

August 1921 -

Books

BooksTHE SUPREME COURT AND JUDICIAL REVIEW,

April 1942 By James P. Richardson '99 -

Books

BooksMARKETING IN AN UNDERDEVELOPED ECONOMY: THE NORTH INDIAN SUGAR INDUSTRY.

JULY 1963 By KENNETH R. DAVIS -

Books

BooksHISTORY OF GRANVILLE, MASSACHUSETTS.

March 1955 By NATHANIEL L. GOODRICH -

Books

BooksFUNDAMENTALS OF SOCIAL SCIENCE

October 1946 By Robert K. Carr '29 -

Books

BooksAMERICA MOVES WEST

February, 1931 By W. R. Waterman