"Erroneous History"

To THE EDITOR: If your report in the May issue of President Jordan's lecture on The Meaning of Tolerance (in the Great Issues Course, March 8, 1948) is correct, the students on that day were given some fantastically erroneous American history.

1. The statement on p. 15 that those who drafted the First Amendment sought to implant "in our Constitution the doctrine of absolute separation of church and state" is simply not true. The Amendment was drawn, according to Madison, in answer to specific petitions from various states (Pa., N.H., N.Y., Va., R. 1., N.C.), asking for a Bill of Rights which would prevent any single religious sect or society being favored or preferred by law nationally. The established churches in indidividual states were being eliminated. The people wanted to make sure that no national church should be established by Congress to replace the dying state churches. Madison's position was that such a provision was not necessary (because the Federal Government had had no power over such matters delegated to it) but that it was harmless if carefully worded. He stately clearly that this was his exact purpose. (See Annals of Congress, Vol. 1, pp. 729-731.)

2. The statement (same page) "the separation of church and state, including public education, is clear, clean, and complete in our history and in our Constitution" is again the exact opposite of the truth,—both in historical fact and in constitutional law. The greatest American scholars in constitutional law (Story, Cooley, Corwin, etc.) all deny it. The Federal Government began supporting religion and religious education with tax money in the -First Congress, and has been doing it ever since; it is still doing it today. The same Congress that wrote the Bill of Rights started the chaplain system for Congress, and Madison was a member of the jointcommittee that arranged it. The use of Federal taxes to support religion and religious education among the Indians continued from 1789 to 1900. Chaplains in the Army and the Navy, compulsory attendance at religious exercises at West Point and Annapolis, the School Lunch Bill, and the G. I. Bill of Rights are other proofs that we have never had absolute separation of church and state in the United States. Nor have we had it for so much as one day in any state in the Union. Until the latter part of the 19th century American public school systems used public funds to promote "Trinitarian Protestant Christianity" almost universally. (Beale's History of the Freedom of Teaching, Chapters 1-4.)

3. The "absolute separation of church and state" is not and never has been a constitutional or an American principle. It is a strictly modern propaganda slogan used by those who find our Constitutional policy of religious equality and religious freedom on a national basis, plus the complete responsibility of the several states for government control of such domestic matters as religion and education within the states, unsuited to their purposes. Capturing or destroying the First Amendment's first clause is necessary if these propagandists are to force their ideas on the American people without consulting the wishes of the people as prescribed in the Constitution. The responsible representatives of the American people in Congress have repudiated again and again attempts to put state restrictions in the matter of religion and education into the Constitution. Twelve'such proposals were defeated in the last great period of attack on the First Amendment, 1870 to 1890. An edict by the Supreme Court in total disregard of both history and semantics is the only hope of those who do not like our historical and constitutional arrangements for the relations of government and religion.

The attack is succeeding. On the day on which President Jordan gave his lecture in Hanover the Supreme Court handed down its decision in the McCollum case. This is a revolutionary decision, reversing the total record of the Supreme Court decisions, the total record of Congress, and the total record of the Presidency. Both Jefferson and Madison, as well as all other presidents from, Washington to Truman both inclusive, used' public funds in aid of religion. Every state in the Union has a large number of cooperating contacts between government and religion or religious education. Jhe McCollum decision, for the first time in our history, denies to the people of a state the precise freedom in matters of religion which the religious clause of the First Amendment was designed to preserve to them—complete freedom from national dictation.

This decision was based almost exclusively on the erroneous dicta in the majority decision in the Everson case (in which Justice Black substantially misquoted both Jefferson and Madison) and on the dissenting opinion of Justice Rutledge in the same case. I have been studying arguments professionally for over forty years (ever since I had English 9 with Laycock!). The Rutledge argument as to both historical accuracy and. sound logic was the worst I had ever found from a responsible source—until I read the Frankfurter opinion in the McCollum case!

The First Amendment's religious clause does not even proscribe "an establishment of religion." It says Congress shall not touch the subject. It leaves this matter in the hands of the states. It is a "keep out" order only. It contains no religious attitude or doctrine of any kind. It is a purely political item having to do exclusively with the division of powers between state and nation. It left all arrangements between government and religion, or "Church and State," exactly as it found them. In a number of states (Mass., N.H., and Conn.) an establishment of religion (i.e. a position of exclusive favor or privilege granted to one religion or church by the government) continued for many years after the adoption of the Bill of Rights.

I am expressing no opinion of the wisdom of either the New Jersey or the Illinois laws involved in the two cases mentioned. The wisdom of these laws is none of my business or of the businesses of the Justices. of the Supreme Court. Their problem, which they avoided with a completeness requiring most careful thought, was whether these state laws involved "an establishment of religion" as the phrase is used in the First Amendment. To settle this problem requires only ordinary literacy plus a familiarity with the vocabulary of men in American public life in the 18th century, such as Jefferson and Madison. Clearly the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) could not make "the absolute separation of church and state" a restriction on the states unless that doctrine is expressed in the First Amendment. The Fourteenth in this matter can be only a channel.

The words "separation", "church", and "state" are all so thoroughly ambiguous that no one o£ them ever has definite meaning except as such meaning is given to it by its particular context. Such vague language does not belong in constitutions, laws, or court decisions. Since the phrase "separation of church and state" is not found in the United States Constitution (nor in the constitution of any American state) it has no constitutional context and therefore can have no constitutional meaning whatsoever.

Brooklyn, N. Y.

Mr. O'Neill is Professor and Chairman ofthe Department of Speech at Brooklyn College. He taught at Dartmouth from 1909 to1913. The relationship of Church and Statehas been his special study for many years, andhe is the author of "Religion and EducationUnder the Constitution."

A Dream League

To THE EDITOR: As editor of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE I suppose you are a fair target for all sorts of queer ideas, especially from us old coots who are out of touch with affairs. So I take the liberty of relating to you what seemed to me to be a strange fantasy, if that is the word. You may throw it into the waste basket or pass on the gist to whomever you please, at least I shall have relieved myself of the urge to spread the idea. At first I thought of sending it to your manager of basketball, but I was afraid he might have little respect for gray hairs. Well, here goes!

A few nights ago I woke from sound sleep to be aware that my subconscious mind had evidently been hard at work planning an International Basketball League with games planned so that teams from each and every country, race and nation would carry out an extensive schedule of games in every other, rather than having only the champion from each section compete with other champions. If some region did not have a team, others could arrange exhibition games in that region.

That gives you the idea. I will not try to talk about feasibility, sponsors, and working details; nor whether the effects would be to increase the mutual understanding among nations. To those who may be interested these questions will work themselves out. What I want to say is that it seems so strange that this should be in my thoughts, because I am not a basketball man and I have done no more than casual thinking about international affairs.

Danielson, Conn.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Books

BooksDeaths

June 1948 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912

June 1948 By HENRY K. URION, RALPH D. PETTINGELL, ROSCOE G. GELLER -

Article

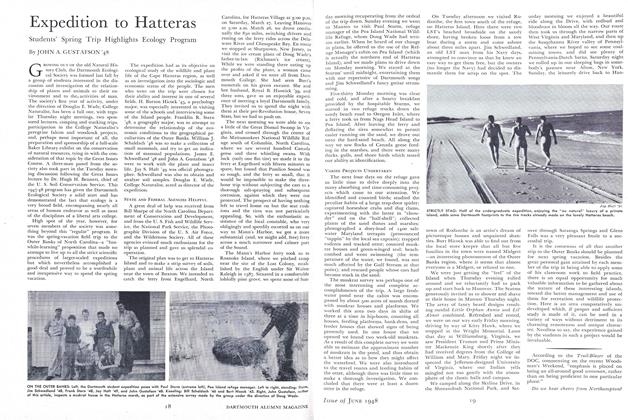

ArticleExpedition to Hatteras

June 1948 By JOHN A. GUSTAFSON '48 -

Article

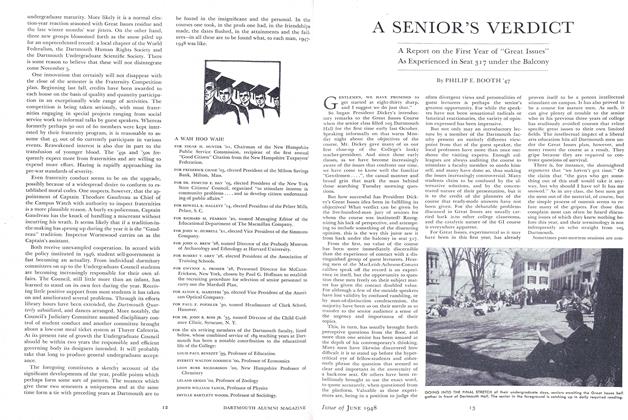

ArticleA SENIOR'S VERDICT

June 1948 By PHILIP E. BOOTH '47 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

June 1948 By FRED F. STOCKWELL, WILLIAM T. MAECK, JOHN A. KOSLOWSKI