The author is the wife of Everett M.Baker '24, Dean of Students at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the recipient in June of Dartmouth's honoraryDoctorate of Divinity. The article first appeared in the magazine YANKEE, whoseeditors have graciously given us permission to reprint it.

JOHN SPAGETT is dead they tell me,—is dead and buried in that little Italian village on a hillside. John who, on a hot August afternoon, staged in that same village ten minutes of football we will never forget, even when our memory becomes hazy about games we have seen in the Yale Bowl and the Harvard Stadium.

You remember him? Well, if you are doubtful, go up to the attic and look in that box beside the chimney. If you can get past the old letters, football programs, and class picture of boys you can't identify for the life of you, way down at the bottom you will find a six-inch statuette and a college seal plaque. John sold you those at Dartmouth, or Amherst, or Williams, or wherever you were if you were sometime between 'O9 and '29.

You couldn't forget that stuttering, vociferous, friendly Italian if you ever really got to know him. He was no ordinary peddler—not by a long shot. It is true he did sell plaster of Paris atrocities which ranged indiscriminately between a figure of St. Joseph and a John Held, Jr., flapper of the early '2o's, but that was only half the story. Part of the rest of it was that students often entrusted him with the most personal of messages to be delivered to a friend in another college, he was sometimes asked to collect over-due bets, and to top all his attributes, there are boys who say they learned more about Italian art from him than ever got through to them in any classroom.

When he arrived in town, he used to set up his wares in some conspicuous place, dispose of them easily, and at the end of the day go to some fraternity house to spend the evening. There he would sit by the fire and talk about Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci, Andrea del Sarto and others as if they were his own sons, then he would start on Eddie Mahan, Charlie Brickley, "Tack" Hardwick and go right down the line of football heroes, dealing with them with equal authority and enthusiasm.

The Harvard-Dartmouth game was the peak of the year for him but when Harvard won he wept,—first because of his loyalty to the team from Hanover and second because of his feud with John, the orange man, who had been responsible for keeping him out of the Yard at all times. I imagine it is the only case in history where the orange market versus the plas- ter of Paris market determined the preju- dice against Harvard!

John's other enthusiasm was his farm near Pisa where he spent his summers visiting his wife and children. He had substituted the tips he had picked up on the side at Massachusetts Agricultural College, for holy water, and said he had abandoned the latter method entirely. When was he going back for good? Oh,—maybe next year, maybe the year after,—"and b-b-boys," he would stutter, "if you ever get to Pisa, c-come to Borgo Morzano and I'll give you such wine from my vineyard as you have n-n-never tasted."

"Sure, John," they all said. "Bet your life." It sounded pretty good on a cold winter's evening in New England,—sunny Italy, travel-poster blue skies, purple wine, —yes, they would go sometime, but of all those who said, "Sure, John," I know of only one student who actually showed up in Borgo Morzano. Before everything turned upside-down over there, my husband and I went to Italy and called on Americus Bernardi—John Spagett to you!

The high-lights of getting to his place from Pisa were a twenty-five mile rough ride in a taxi to a tiny village and our discovery that we were so far from the beaten track of tourist agencies, our Italian vocabulary of "how much," 'too much," "yes," "no," "beautiful, beautiful," and "good-bye," was totally inadequate. We finally wrote John's name on a slip of paper and that got us started on a two-mile climb in the wake of a girl and a .burro. When we reached a group of houses built on the hillside, we were led to the most prosperous looking one and escorted into the courtyard by several children.

Two women were setting a long wooden table. They both looked up as we entered and the younger who, by her dress and hair-do, was obviously an outsider, spoke to us in English. When we told her that we had come to see Mr. Bernardi, she greeted us warmly and told us that she was his sister from Dorchester, Mass. Before we had time to pull out the old cliche, "it's a small world, etc.," we heard someone approaching from the direction of the vineyard. He was whistling an air from "Aida." I looked at my husband, he smiled and nodded his head.

This was the moment we had driven twenty-five rough miles for, had climbed a small mountain for,—"b-b-boys, if you ever get to Italy,"—how many had we figured he must have said that to through the years? Would he remember one out of the lot? I was conscious that four or five more people had come into the courtyard, and they, the sister, the wife and we foreigners stood silently watching the gate-way.

He came, head down, then looked up and saw us. He stopped dead, dropped the pails he was carrying, clasped his brow with both hands and rushed towards us shouting, "B-B-Baker-D-D-Dartmouth DKE, the best friend I have in America." The tears streamed down his face. He embraced my husband and kissed him on both cheeks, then held him at arm's length and embraced him again, saying over and over, "My friend from America. Mio Dio!"

We three sat down on a bench and John hurled a volley of questions at us about the boys,—where certain ones were, what they were doing,—what about the teams? -how did they look last year?-where was Oberlander? What about Dooley? Had there been any runs like the ones made by Pat Holbrook and Jim Robertson? "What! Baker didn't remember? Mio Dio! Surely he remembered the time Jim Thorpe led the Carlyle Indians into the Stadium and, -what! He didn't. Jesu, Baker, what did you go to college for? O, that's right—you would have been only about ten years old then. Well, after all there were good games in your day too,—you couldn t beat the time in '23 when—"

Whereupon John jumped to his feet and before fifteen dumbfounded spectators enacted ten minutes of play with such enthusiasm he had us shouting and cheering, rolling our handkerchiefs into little damp wads, pounding each other on the back while John went with himself into a huddle—jumped into position, called the signals—26-47-62-9. He was off! He had the ball ye gods, he was going to pass and no one there to receive it.... we tore our hair,—he threw the ball! No one there? We must have been blind, o£ course there was—none other than John himself who had raced down the field to receive it. What a play! But confound it, he was tackled by himself on the eighteen-yard line—he was down. We heard the whistle —what waSThiUi' It was John penalizinthe team for being off side. Kill the referee! there was blood in John's eye now the game went on—he had the ball againhe was tackled by himself—he pushed himself off—he ran down the field—ten yards \twenty yards—thirty yards,—you couldn't beat the man—he was super-human-by George, he was going to make it. He ran around the end for a touchdown. Then he kicked. Perfect! The score was 7-0.

I was a rag. I thought to myself—if I ever have a son he will not play football. I had never realized how dangerous the game was. It wasn't decent, it wasn't right. But somehow when John came over and hunched down in front of us to lead a cheer, we gave forth a wah-hoo-wah that rang the country-side for miles around and must have shaken all the grapes in the vineyard. What a game! What a team! What a man!

Into the house we went, singing "Dart- mouth's In Town Again." We celebrated the victory by having supper in the parlor, waited upon by Mrs. Bernardi and her six children, while John entertained us by telling of his experiences in selling his wares in Europe,—of how he called one of his statues "Garibaldi" in Italy, but sold it in Belgium as "St. Joseph"; telling us that, thanks to Massachusetts Agricultural College, his vineyard was the best in Borgo Morzano, and telling us, with a wistful look in his eye, that he had settled down for good but that he would give half his land and all his statues to go back just once to see the boys, to go to a good game in the Stadium, and to sit for one evening talking with his friends around the fraternity house fire.

JOHN SPAGETT on the Webster Hall steps during one of his visits to Dartmouth in the '20s.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe President Comments On the Cirrotta Tragedy

October 1949 By /S/ John S. Dickey -

Sports

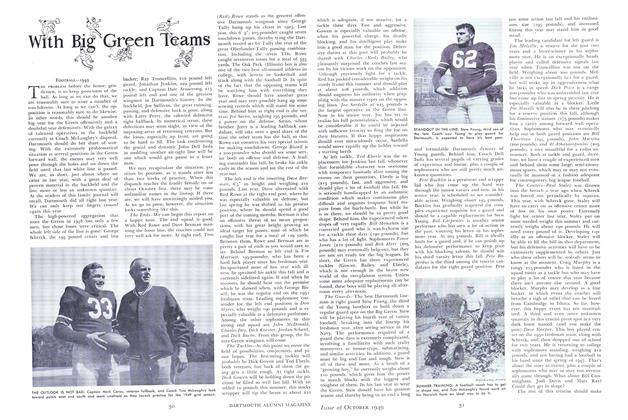

SportsFOOTBALL—1949

October 1949 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Seeks Growth of Its Scholarship Funds

October 1949 By ROBERT L. ALLEN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1949 By ERNEST H. EARI.EY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

October 1949 By E. PAUL VENNEMAN, HERBERT F. DARLING, ROBERT M. STOPFORD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

October 1949 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART, 3rd, JULIUS A. RIPPEL

Article

-

Article

ArticleOUTING CLUB

April, 1912 -

Article

ArticleENGLISH DEPT. PUBLISHES BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR ALUMNI

November 1923 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

May 1955 -

Article

ArticleFletcher Clark '12 Honored as Class Treasurer of the Year

JUNE 1968 -

Article

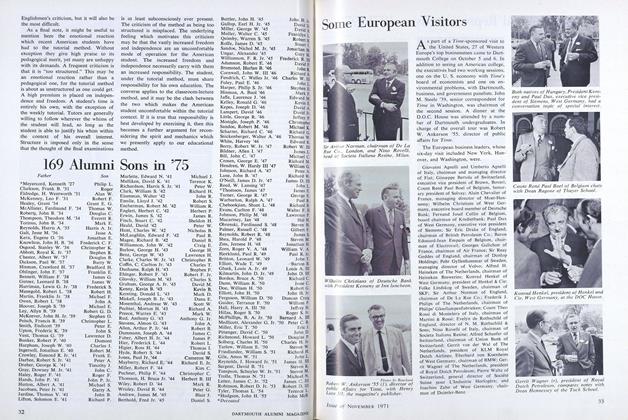

Article169 Alumni Sons in '75

NOVEMBER 1971 -

Article

ArticleVoces

DECEMBER 1997 By Heather McCutchen '87