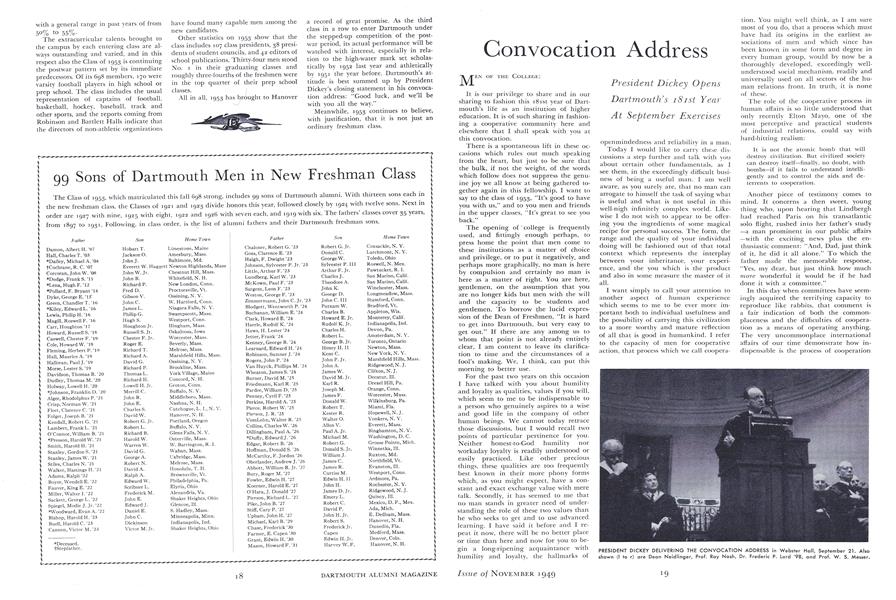

President Dickey OpensDartmouth's 181st YearAt September Exercises

MEN OF THE COLLEGE:

It is our privilege to share and in our sharing to fashion this 181st year of Dartmouth's life as an institution of higher education. It is of such sharing in fashioning a cooperative community here and elsewhere that I shall speak with you at this convocation.

There is a spontaneous lift in these occasions which rules out much speaking from the heart, but just to be sure that the bulk, if not the weight, of the words which follow does not suppress the genuine joy we all know at being gathered together again in this fellowship, I want to say to the class of 1953, "It's good to have you with us," and to you men and friends in the upper classes, "It's great to see you back."

The opening of college is frequently used, and fittingly enough perhaps, to press home the point that men come to these institutions as a matter of choice and privilege, or to put it negatively, and perhaps more graphically, no man is here by compulsion and certainly no man is here as a matter of right. You are here, gentlemen, on the assumption that you are no longer kids but men with the will and the capacity to be students and gentlemen. To borrow the lucid expression of the Dean of Freshmen, "It is hard to get into Dartmouth, but very easy to get out." If there are any among us to whom that point is not already entirely clear, I am content to leave its clarification to time and the circumstances of a fool's making. We, I think, can put this morning to better use.

For the past two years on this occasion I have talked with you about humility and loyalty as qualities, values if you will, which seem to me to be indispensable to a person who genuinely aspires to a wise and good life in the company of other human beings. We cannot today retrace those discussions, but I would recall two points of particular pertinence for you. Neither honest-to-God humility nor workaday loyalty is readily understood or easily practiced. Like other precious things, these qualities are too frequently best known in their more phony forms which, as you might expect, have a constant and exact exchange value with mere talk. Secondly, it has seemed to me that no man stands in greater need of understanding the role of these two values than he who seeks to get and to use advanced learning. I have said it before and I repeat it now, there will be no better place or time than here and now for you to begin a long-ripening acquaintance with humility and loyalty, the hallmarks of openmindedness and reliability in a man.

Today I would like to carry these discussions a step further and talk with you about certain other fundamentals, as I see them, in the exceedingly difficult business of being a useful man. I am well aware, as you surely are, that no man can arrogate to himself the task of saying what is useful and what is not useful in this well-nigh infinitely complex world. Likewise I do not wish to appear to be offering you the ingredients of some magical recipe for personal success. The form, the range and the quality of your individual doing will be fashioned out of that total context which represents the interplay between your inheritance, your experience, and the you which is the product and also in some measure the master of it all.

I want simply to call your attention to another aspect of human experience which seems to me to be ever more important both to individual usefulness and the possibility of carrying this civilization to a more worthy and mature reflection of all that is good in humankind. I refer to the capacity of men for cooperative action, that process which we call cooperation. You might well think, as I am sure most of you do, that a process which must have had its origins in the earliest associations of men and which since has been known in some form and degree in every human group, would by now be a thoroughly developed, exceedingly wellunderstood social mechanism, readily and universally used on all sectors of the human relations front. In truth, it is none of these.

The role of the cooperative process in human affairs is so little understood that only recently Elton Mayo, one of the most perceptive and practical students of industrial relations, could say with hard-hitting realism:

It is not the atomic bomb that will destroy civilization. But civilized society can destroy itself—finally, no doubt, with bombs—if it fails to understand intelligently and to control the aids and deterrents to cooperation.

Another piece of testimony comes to mind. It concerns a then sweet, young thing who, upon hearing that Lindbergh had reached Paris on his transatlantic solo flight, rushed into her father's study —a man prominent in our public affairs —with the exciting news plus the enthusiastic comment: "And, Dad, just think of it, he did it all alone." To which the father made the memorable response, "Yes, my dear, but just think how much more wonderful it would be if he had done it with a committee."

In this day when committees have seemingly acquired the terrifying capacity to reproduce like rabbits, that comment is a fair indication of both the commonplaceness and the difficulties of cooperation as a means of operating anything. The very uncommonplace international affairs of our time demonstrate how indispensable is the process of cooperation at the highest levels and in every phase of human affairs. Cooperation in all literal truth is the very fabric of the cohesiveness which we call by the word "community." It matters not whether that community be the Dartmouth community which it is our privilege to fashion this year, or at the other end of the same spectrum, the world community whose fashioning is the business of all peoples.

Have stopped to think about the functional ingredients of that nice, comfortable word "cooperation"? At the base of any cooperation there must be one thing, namely, a sense of common purpose between two or more individuals. It matters not, gentlemen, whether you are talking about the United Nations, or just two nations, or even just you and your teachers here at Dartmouth, there is no possibility of genuine cooperation unless at least two men have reached an honest common purpose as to what they are going to do together. In its most complex forms the process involves the creation of some sense of common purpose among millions. Today, however, I want to hold you to the point above all else that learning to recognize and to serve a common purpose with other men begins for you right here in the classroom, on the field, in the dormitories, in the fraternities, in the commons, or wherever else two or more Dartmouth men are met together to work or to play within the purposes of this liberal arts college.

It is probably important to say that a common sense of purpose is not the same thing as having an identical interest with another man or nation in a matter. In the most precise sense I doubt that any two individuals or nations ever have or ever could have exactly identical interests. The infinite variability of the factors of inheritance, experience and time seem to me to preclude that, but I quickly add that the self-interest of individuals and nations, in its most exact and particular sense, seems to me today, for all practical purposes, to be beyond realization except through the processes of cooperation and the development of common purposes on which those processes rest. If you really understand that and agree with it, it will make a difference in the life you live here at Dartmouth and thereafter.

There are three situations in today's international affairs which are highly instructive as to the necessity, the possibilities and the limitations of international cooperation as an approach to the well-being of nations. The course of the occupations of western Germany and Japan are first-rate case studies in the truth that no reliance can be placed on indefinite and unilateral repression as a long-range or general solution for any problem in human affairs. Students of human behavior have long observed that a healthy human mind finds it virtually impossible to sustain indefinitely a peak of intense hostility. Every seasoned prison administrator knows, for example, that even among the so-called "lifers" a relatively small percentage end their lives in prison. And history gives little reason to believe that succeeding generations will resolutely police international solutions of suppression however justly these solutions were founded in the grievances and hostilities of a past generation. If this be so, it seems to me that in the midst of all our troubles and misgivings this nation can congratulate itself on the broad strategy which has been followed in carrying out our occupation responsibilities. We have used the period of inevitable hostility to get some necessary things done by unilateral action and severity. And we now seem to be facing up realistically to the counter inevitability and necessity of seeking the long-range solutions through the processes of cooperation and agreed action. From here on it's uphill going for a long time.

And if in our discouraged moments we need concrete assurance as to the possibilities of cooperative action I should point to the concept of the Marshall plan and the job being done on that front by men of good-will whose hard work is building a foundation of common purpose on which a free Europe can be reconstructed.

The limitations of cooperative action in any community are illustrated, I think, in the situation which exists between the nations in the orbit of the Soviet Union and the rest of the world. Here for some time now there has been little or no cooperation in any field. There is at present no serious search for anything except the most limited common purposes. The reason for this is clear—there can be no cooperation with a conspiracy directed against oneself. As between the Soviet and the West, each regards the other as conspiring its downfall and the situation is such that each asserts the necessity of defensive measures. For my part I believe the Soviet Union has largely brought this, situation down on its own head and that the conspiratorial methods of international communism have no place in communities whose people seek to work out their destiny through the cooperation of free men. Whether those who hold this view are right or wrong, it is at best going to take time and highly mature statecraft to get us out of these close waters and again into the navigable open seas where with a certain elementary respect for navigation rules there at least used to be room for the national pursuit of highly diverse domestic ideologies.

No man can see with certainty just how this can be done and conceivably it cannot be done, but whatever your personal estimate of the probabilities may be, it is also a fact that no man knows that we cannot come out of it peacefully. The man in this country or the Soviet Union who knows that now is a fool and a knave in about equal proportions.

On the other hand I am not at all clear that we can assume an indefinitely extended period during which there might very gradually be worked out some such accommodation between East and West as has brought peace and stability to the world in the wake of past seemingly irreconcilable religious conflicts. The factors of distance, communication, and capacity for destruction are so drastically altered that I prefer to leave solely to the calculations of the Almighty any reliance on the fact that in the past time has cured all things.

It seems there are two complementary courses open to us. On the one hand, while remaining strong enough for the worst and holding firm on principle in negotiation, to watch honestly and carefully for any genuine change in the Soviet's fundamental external policies or for any convincing proof that our estimate of their policies and purposes is mistaken in any degree. This is the course of keeping the road open in our own minds for such cooperation as can be realized if and when.

On the other hand and at the same time it is to our interest, whatever the course of Soviet purposes, to use the precious time now in our hands to push forward more vigorously the processes of international cooperation in creating the fabric of an international community strong enough either to attract to it the adherence of a more friendly Soviet or to repel any thought of aggressive policies on the part of a Soviet remaining aloof and apart. Boldly and promptly pursued, this course holds within its promise both the performance of today's pressing practicalities and the quickest possible realization of the no less pressing ideals of those who truly understand both the strength and the limitations of the cooperative process at the present stage of human development.

I cannot do better in summary than to give you the words of the late Professor Patten, one of Dartmouth's great teachers—

"When we realize that evolution is the summation of power through cooperation, that what we call 'evil' is that which prevents or destroys cooperation, and 'good' is that which perpetuates and improves cooperation; when we realize that the 'struggle for existence' is a struggle to find better ways and means of cooperation, and the 'fittest' is the one that cooperates best—we shall realize that science and religion and government stand on common ground and have a common purpose ... The chief service of cooperative action ... consists in the conveyance of the right kinds of power to the right times and places for further cooperative action."

Gentlemen, the fashioning of your usefulness to yourself and society as openminded, reliable and cooperative men is in your hands.

And now, men of Dartmouth, as I have said on this occasion before, as members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such. Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be. Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you.

We'll be with you all the way and "Good Luck!"

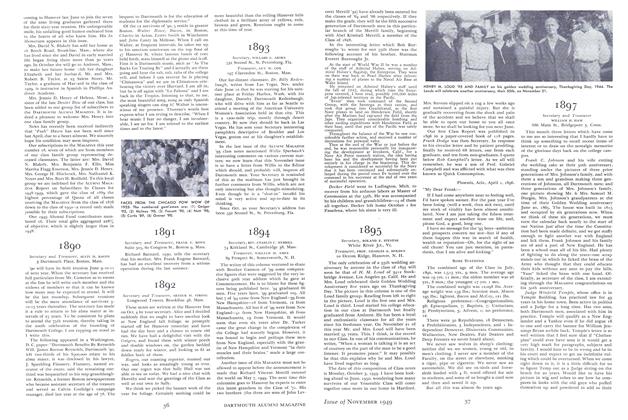

PRESIDENT DICKEY DELIVERING THE CONVOCATION ADDRESS in Webster Hall, September 21. Also shown (I to r) are Dean Neidlinger, Prof. Ray Nash, Dr. Frederic P. Lord '98, and Prof. W. S. Messer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1949 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

November 1949 By WILLIAM H. HAM -

Article

ArticleEnglish Climbing Boys

November 1949 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

November 1949 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART, 3rd -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912

November 1949 By HENRY K. URION, RALPH D. PETTINGELL, HENRY B. VAN DYNE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

November 1949 By FRANKLYN J. JACKSON