They Are the Subject Of Ten Years' Study by George L. Phillips '31

ASA DARTMOUTH UNDERGRADUATE, George L. Phillips '31 let himself go in his love for antiques. He did not mind if they were not to be found near athletic fields. His hobby so far removed from student outdoor life caused no little comment among his professors and decidedly more among his classmates.

He explored the New Hampshire countryside for antiques which would express properly his personality. Some of them he had money enough to buy, and he arranged and rearranged them in his room, where not a single college pennant could be found. His room was in a house on the main street of Hanover next to the present Post Office—the so-called Daniel Webster House owned by Mrs. Pierce Crosby, who filled it so full of furniture that a person could hardly maneuver from room to room, though her dogs could. It has since been rebuilt, repainted, and refurnished with antiques by Harry Heneage's daughter, Sylvia Porter, known to Dartmouth alumni who come looking for rarities in her shop.

After leaving college George Phillips might easily have gone into the antique business. While still a student he had browsed around in England and written of his experiences in his Dartmouth composition courses. But it was just as natural for him to enjoy his literary tastes in the graduate schools at Harvard and Boston University, where he got his Ph.D. in English, and to become an English instructor. During his studies there he lived for a couple of years on Beacon Street, Boston, in a house filled with old furniture and pictures which its elderly owner had picked up in her travels through England and on the Continent. The little treasures from Lyme, Quechee, West Lebanon, and Orford found their resting places among the great treasures from Europe.

English literature and interest in household accoutrements of earlier centuries led George Phillips from poetry to tongs and firedogs and from humanitarian tracts to chimneys and climbing boys. Even in Brazil, Switzerland, France, and Italy, countries where he spent four years during the war in the Foreign Office of the United States, he never failed to seek out antique shops and to ferret out new facts about sweeps in literature and life.

Now he stands in an abiguous role. He is known as an expert on Italian antiques in Southern California because with his wife Helga he has a shop in La Jolla specializing in furniture from past centuries discovered in Italian cities and shipped over in crate after crate to this country. In San Diego, where he has an assistant professorship in English at San Diego State College, the newspapers are likely to refer to him as Dr. Phillips, the Savant, teaching a course in the eighteenth-century British novel. On the North Atlantic Coast, especially at Harvard University, he is known as Mr. Phillips, the expert on chimney sweeps and the most distinguished collector in the United States of Sweepiana, books and prints concerned with climbing boys in this country but more especially in England.

The ten-year investigation into the fortunes of climbing boys unfolded for George Phillips a fascinating if macabre series of tableaux. The result is a book, England's Climbing Boys, A History ofthe Long Struggle to Abolish Child Laborin Chimney Sweeping, published by Baker Library, Harvard Graduate School of Business Administration, Boston, 1949. Copyrighted by the President and Fellows of Harvard College, it is Publication Number 5 of the Kress Library of Business and Economics and contains a Preface by Arthur H. Cole, Professor of Business Economics and Librarian of Baker, who describes Mr. Phillips's essay as "enlightening and engaging." Thanks in part to Mr. Phillips, the Kress Library has assembled books and prints concerning chimney sweeps which make the collection the second best in this country.

The essay runs to 56 pages with five additional pages containing a bibliography of the books and pamphlets, most of them rare. A reader approaching the subject for the first time is struck with the confidence of the British in tradition and class distinction as shown in their reluctance to change their ways. Many noble lords through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries even insisted that sweeps had a good life, despite glaring examples of barbaric mistreatment, and that their apprenticeships built up their characters, despite overwhelming proof to the contrary.

One boy, for example, consented to the amputation of a leg when a surgeon assured him that he would thereafter be unfitted for flue work. One 11-year-old apprentice got stuck in a flue more than usually narrow and struggled in agony for five hours. His Master Joseph Rae "sent another apprentice up the flue to attach a cord to one of his legs. Despite the agonized shrieks of the tortured boy, Rae and another man hauled on their end of the rope with all their strength. Finally when neither shrieks nor groans were heard, Rae, sensing that the boy was dead, drank a dram of whiskey and left the house."

Some boys slept on soot-bags in damp unheated cellars and developed asthma; and some, undernourished and inadequately clothed, fell ill with tuberculosis and could not work. Nearly all suffered from red-rimmed eyes and eyelids inflamed from soot particles. Most dreaded of all afflictions was cancer of the scrotum. Every boy was thankful to escape with knocked knees, swollen ankle joints, and raw and bleeding elbows from flue friction though they never could become inured to falling down chimneys on to lighted fires and getting large portions of their anatomies burned off.

Whimsical and romantic, Charles Lamb wrote an essay, Praise of Chimney Sweepers, and Thomas Hood in a poem compared them to blackbirds in spring. Factual and analytic, George Phillips shows that their cries on the street of "Sweep, Sweep" were no songs, for employed when only six, five, and even four years old as "living brushes," they were pathetic victims of a heartless system.

Thus the final essay emerging from monographs written over a decade is concerned with such sociological and economic phenomena in England as the rapid increase in population, the growing cleavage between the owning and wageearning classes, the enjoyment of brutality or at best the indifference to suffering, and the inadequacies of the English to administer social reform until after long years they finally perceived that it was necessary. As early as 1804, George Smart discovered a mechanical brush which made a "human brush" obsolete.

An author may turn over half a library before he finds an idea for a book. As a graduate student, Mr. Phillips was doing research for his dissertation on Ebenezer Elliott, an English poet called the Corn-Law Rhymer, who attributed all national misfortunes to the bread tax which he denounced bitterly in his Corn-Law-Rhymes (1831) and who was also interested in the plight of climbing-boys. Pursuing this lead, Mr. Phillips investigated the activities of a better poet, James Montgomery, who was also editor of the Sheffield Iris, and Samuel Roberts, a cutlery manufacturer, who wrote a number of propagandist works on behalf of the poor.

A surprising amount of material concerning sweeps in better known nineteenth-century writers like Dickens, Blake, Lamb, Kingsley, Edgeworth, and Hood in turn led Mr. Phillips to other philanthropic agitators. Eccentric and purposeful as well as charitable, Jonas Hanway busied himself about the betterment of sweeps. Jeered at by hackney coachmen, he also carried around for 30 years a contraption called an umbrella, and he finally set a style and made persons eccentric who did not carry one.

David Porter, son of a chimney sweeper, cleaned flues from the time he was 10 until he turned reformer, repudiated his conversion, and blandly asserted that sweeping was good discipline for boys. It made them industrious and decent.

Dr. Stephen Lushington, an Oxford graduate, on the contrary, told how as a matter of course masters kidnapped young boys or bought them from impoverished parents for a few shillings (the smaller the boys, the higher the prices) and then beat the boys with rods, built straw fires under them when they got stuck in sootfilled flues to stimulate their frantic efforts to escape, how masters were at their most merciful when they merely stuck pins into the boys' legs and kicked their buttocks to assist them on the way up.

Greatest of all nineteenth-century philanthropists was the Earl of Shaftesbury, admirable traitor to his class, who secured final passage in 1875 of the bill emancipating climbing boys.

What these reformers were fighting against may be seen in Mr. Phillips's collection of pictures. It consists of more than 50 original and 100 photostatic copies of sweepdom and ranges from the earliest picture printed before 1530 of John Cottingham, known as Mulled Sack, who combined sweeping with highway robbery, to the latest picture of Joseph Lawrence of Windlesham, Surrey, the last surviving climbing boy, who died July 12, 1949 at the age of 104. When 12 years old, he worked 15 hours a day naked inside chimneys and sometimes climbed 25 in a day. To live to be 104, he said, one should have plenty of work, plenty of games, and a drop of whiskey now and again. On his 104th birthday, Mr. Lawrence charmed listeners by telling them how as a climbing boy he appeared naked before a lady after he had descended a wrong flue. He did have a coating of soot thick enough to conceal his absolute nudity but not enough to make him socially eligible to converse with a lady. So he retreated up the wrong flue, and no gentleman would have done more, if indeed as much.

Speaking of ladies and decency, one is reminded that though at one time London could justifiably boast that it had 100 established master chimney sweepers employing 200 journeymen and 400 climbing boys (not to mention 50 itinerant sweeps and their 150 boys), all these were not enough to insure the comfort of the middle and upper classes. There were also women or what the British more elegantly referred to as "female chimney sweepers."

They are the subject of another essay by the industrious Mr. Phillips in Notesand Queries of July 11, 1949, who suggests that though they may have worn female garments, their hearts failed to flutter in feminine fashion. Most women sweeps, savage as men in their treatment of children in their employ, were subject to the same penalties and restrictions in the Act of 1788.

Indeed, Mr. Phillips comes to the gallant conclusion that the women were often so much better in this business than the men that the men disliked them and showed commercial jealousy. A certain oldtimer named Adolphus Buster, for example, lived up to his name and knocked into the gutter a lady sweep named Angelina Mathilda Colebrook. She sued him. He defended his action saying to the court as he wiped his eyes that the woman was an upstart who had been practising her trade for only 20 years and that it was not fair that she "should go for to take the werry wittles out of my blessed babbies poor hinnocent mouths."

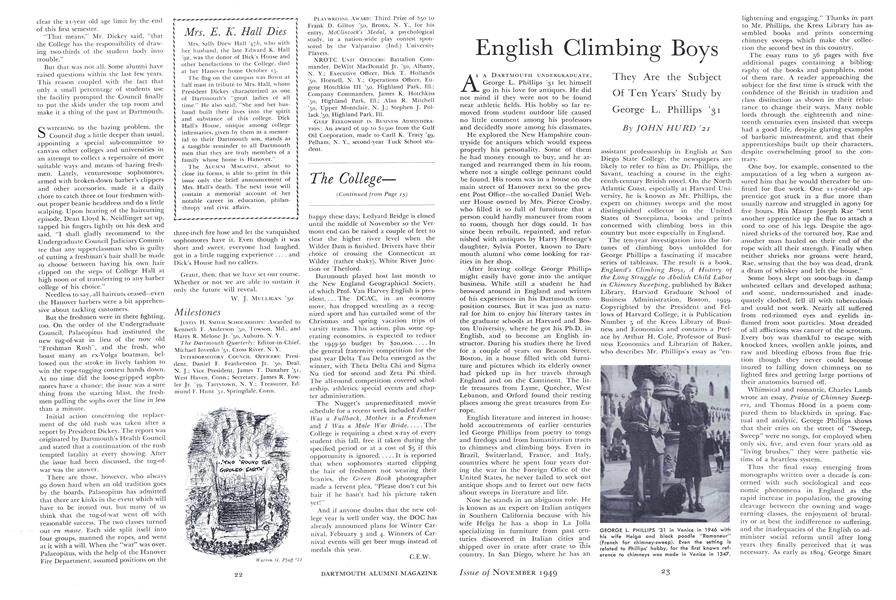

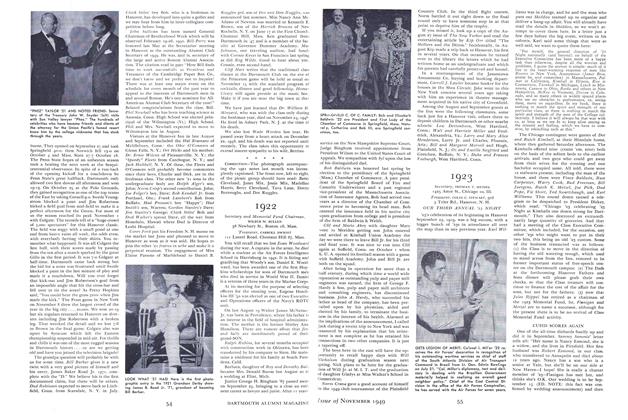

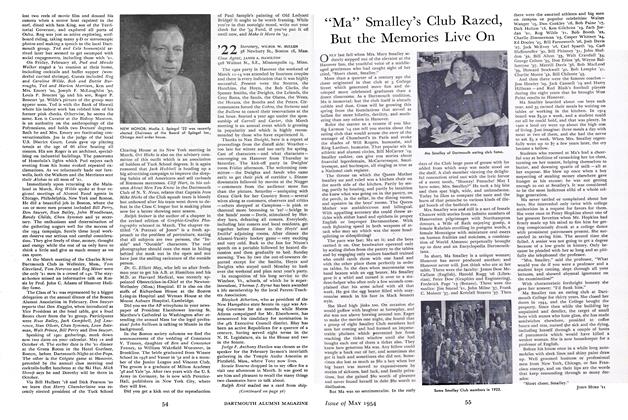

GEORGE L. PHILLIPS '31 in Venice in 1946 with his wife Helga and black poodle "Ramoneur" (French for chimney-sweep). Even the setting is related to Phillips' hobby, for the first known reference to chimneys was made in Venice in 1347.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1949 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Article

ArticleConvocation Address

November 1949 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

November 1949 By WILLIAM H. HAM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

November 1949 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART, 3rd -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912

November 1949 By HENRY K. URION, RALPH D. PETTINGELL, HENRY B. VAN DYNE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

November 1949 By FRANKLYN J. JACKSON

JOHN HURD '21

-

Article

ArticleMan on the Job . . . for Thirty Years

October 1950 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

Article"Ma" Smalley's Club Razed, But the Memories Live On

May 1954 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksOLIVER GOLDSMITH.

February 1958 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksOFF THE SAUCE.

NOVEMBER 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksP AS IN POLICE.

JANUARY 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

Article1972 Course Guide

JANUARY 1973 By JOHN HURD '21

Article

-

Article

ArticleFraternities Combine

June 1935 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah for –

NOVEMBER 1964 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

December, 1919 By A. H. B. -

Article

ArticleUp Hill and Down Dale

MAY 1932 By Everett P. Hokanson '32 -

Article

ArticleVoces

DECEMBER 1997 By Heather McCutchen '87 -

Article

ArticleEmployer Discusses Labor Issue

February 1946 By Norman E. McCulloch '17