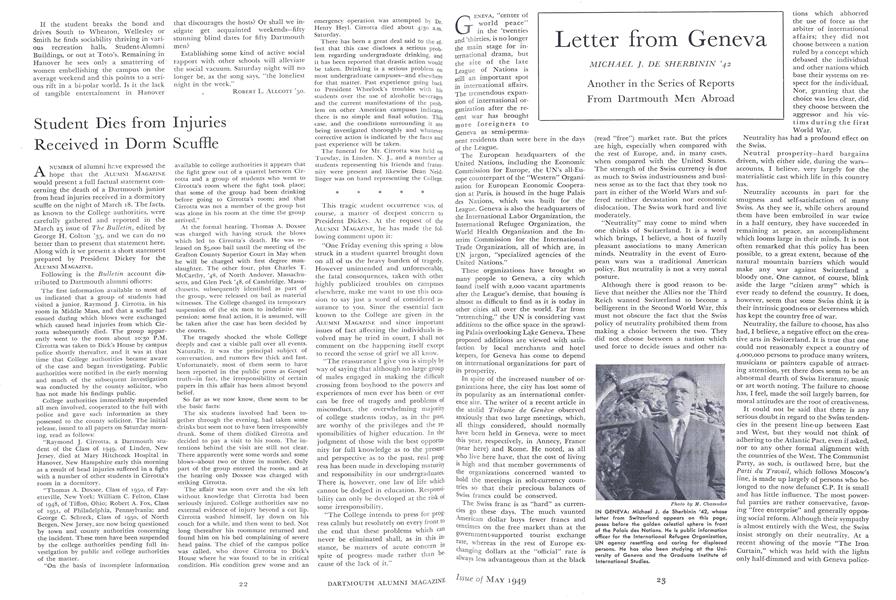

Another in the Series of Reports From Dartmouth Men Abroad

GENEVA, "center of world peace" in the 'twenties and 'thirties, is no longer the main stage for international drama, but the site of the late League of Nations is still an important spot in international affairs. The tremendous expansion of international organization after the recent war has brought more foreigners to Geneva as semi-permanent residents than were here in the days of the League.

The European headquarters of the United Nations, including the Economic Commission for Europe, the UN's all-Europe counterpart of the "Western" Organization for European Economic Cooperation at Paris, is housed in the huge Palais des Nations, which was built for the League. Geneva is also the headquarters of the International Labor Organization, the International Refugee Organization, the World Health Organization and the Interim Commission for the International Trade Organization, all of which are, in UN jargon, "specialized agencies of the United Nations."

These organizations have brought so many people to Geneva, a city which found itself with 2,000 vacant apartments after the League's demise, that housing is almost as difficult to find as it is today in other cities all over the world. Far from "retrenching," the UN is considering vast additions to the office space in the sprawling Palais overlooking Lake Geneva. These proposed additions are viewed with satisfaction by local merchants and hotel keepers, for Geneva has come to depend on international organizations for part of its prosperity.

In spite of the increased number of organizations here, the city has lost some of its popularity as an international conference site. The writer of a recent article in the stolid Tribune de Geneve observed anxiously that two large meetings, which, all things considered, should normally have been held in Geneva, were to meet this year, respectively, in Annecy, France (near here) and Rome. He noted, as all who live here have, that the cost of living is high and that member governments of the organizations concerned wanted to hold the meetings in soft-currency countries so that their precious balances of Swiss francs could be conserved.

The Swiss franc is as "hard" as currencies go these days. The much vaunted American dollar buys fewer francs and centimes on the free market than at the government-supported tourist exchange rate, whereas in the rest of Europe exchanging dollars at the "official" rate is always less advantageous than at the black (read "free") market rate. But the prices are high, especially when compared with the rest of Europe, and, in many cases, when compared with the United States. The strength of the Swiss currency is due as much to Swiss industriousness and business sense as to the fact that they took no part in either of the World Wars and suffered neither devastation nor economic dislocation. The Swiss work hard and live moderately.

"Neutrality" may come to mind when one thinks of Switzerland. It is a word which brings, I believe, a host of fuzzily pleasant associations to many American minds. Neutrality in the event of European wars was a traditional American policy. But neutrality is not a very moral posture.

Although there is good reason to believe that neither the Allies nor the Third Reich wanted Switzerland to become a belligerent in the Second World War, this must not obscure the fact that the Swiss policy of neutrality prohibited them from making a choice between the two. They did not choose between a nation which used force to decide issues and other nations which abhorred the use of force as the arbiter of international affairs; they did not choose between a nation ruled by a concept which debased the individual and other nations which base their systems on respect for the individual. Nor, granting that the choice was less clear, did they choose between the aggressor and his victims during the first World War.

Neutrality has had a profound effect on the Swiss.

Neutral prosperity—hard bargains driven, with either side, during the warsaccounts, I believe, very largely for the materialistic cast which life in this country has.

Neutrality accounts in part for the smugness and self-satisfaction of many Swiss. As they see it, while others around them have been embroiled in war twice in a half century, they have succeeded in remaining at peace, an accomplishment which looms large in their minds. It is not often remarked that this policy has been possible, to a great extent, because of the natural mountain barriers which would make any war against Switzerland a bloody one. One cannot, of course, blink aside the large "citizen army" which is ever ready to defend the country. It does, however, seem that some Swiss think it is their intrinsic goodness or cleverness which has kept the country free of war.

Neutrality, the failure to choose, has also had, I believe, a negative effect on the creative arts in Switzerland. It is true that one could not reasonably expect a country of 4,000,000 persons to produce many writers, musicians or painters capable of attracting attention, yet there does seem to be an abnormal dearth of Swiss literature, music or art worth noting. The failure to choose has, I feel, made the soil largely barren, for moral attitudes are the root of creativeness.

It could not be said that there is any serious doubt in regard to the Swiss tendencies in the present line-up between East and West, but they would not think of adhering to the Atlantic Pact, even if asked, nor to any other formal alignment with the countries of the West. The Communist Party, as such, is outlawed here, but the Parti du Travail, which follows Moscow's line, is made up largely of persons who belonged to the now defunct C.P. It is small and has little influence. The most powerful parties are rather conservative, favoring "free enterprise" and generally opposing social reform. Although their sympathy is almost entirely with the West, the Swiss insist, strongly on their neutrality. At a recent showing of the movie "The Iron Curtain," which was held with the lights only half-dimmed and with Geneva policemen in the theater (the Parti dn Travail had threatened demonstrations), a notice was flashed on the screen urging the audience "not to forget that Switzerland is neutral."

The Swiss have very little interest in politics, especially when compared to their neighbors in France, where, in every cafe, one hears informed and often heated political discussions. Women still do not vote in Switzerland, and in two recent referendums (in which, of course, only men voted) on the proposition, advocates of woman suffrage have been overwhelmingly defeated. The women themselves don't seem interested in obtaining the vote, preferring to leave "such matters" to the men.

The lack of interest in politics is hard to explain. Most Swiss working people do not make much money ($100 a month for a tri-lingual stenographer in a city of 200,000 people is "big money"), and the cost of living is high. The working people seem in this respect as in others to be inert and sluggish. They seem content with very little, a glass of beer, a hike in the mountains, which is perhaps commendable, but one cannot help wondering if they never reflect on the contrast between their meager salaries and the cost of living. Nor do they seem to notice that there is a class of people-shop and hotel keepers, factory owners, etc.—which is well off, and which contrives to maintain its position through high tariffs, restrictions on going into business, agreements between competitors on minimum prices and so on. The answer may that even with things as they are they are better off than their German, French or Italian neighbors, and they take that into consideration.

For the rest, the Swiss are largely humorless people and often have an over-hearty manner. They are among the most honest people in the world; as Ed Bock noted in an earlier "Letter from Europe," in those countries untouched by the war the social structure has remained intact and honesty is still the rule. One can leave an unlocked bicycle on any street in Geneva and return 24 hours later to find it where he left it. A Genevois who loses a small sum of money in the street will apply to the city Lost and Found Department, expecting, as a matter of course, that it has been turned in by another burgher, and he is usually right.

Switzerland expects again to be spared in the event of another world conflict, but it would seem that such a war would be even more "total" than the last. If that were to be the case and Switzerland were attacked, it seems likely she will have chosen to go it alone. But a 700,000-man citizen army and high mountains seem ineffective weapons in any struggle which may come. With their background of luck during two world wars, they are, as a Swiss acquaintance remarked, "looking for security for fifty, a hundred years." But they want it in terms of a world of yesterday, without alliances with other nations.

IN GENEVA: Michael J. de Sherbinin '42, whose letter from Switzerland appears on this page, poses before the golden celestial sphere in front of the Palais des Nations. He is public information officer for the International Refugee Organization, UN agency resettling and caring for displaced persons. He has also been studying at the University of Geneva and the Graduate Institute of International Studies.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

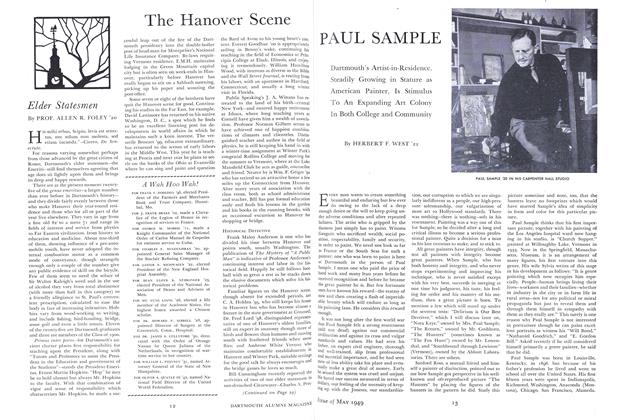

ArticlePAUL SAMPLE

May 1949 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

May 1949 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1949 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONAIJS L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

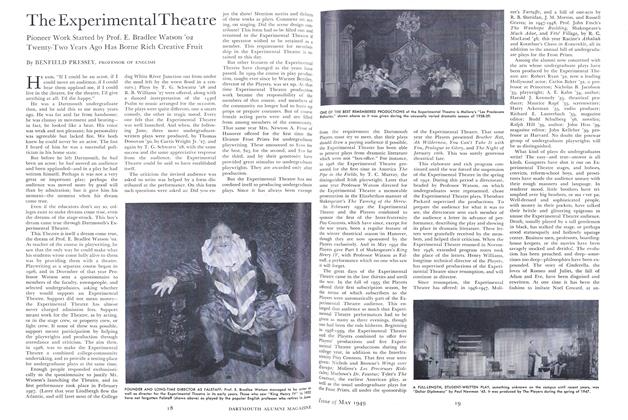

ArticleThe Experimental Theatre

May 1949 By BENFIELD PRESSEY, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

May 1949 By A. W. LAUGHTON, WILLIAM H. SCHULDENFREI, EDWIN F. STUDWELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

May 1949 By FRANKLYN J. JACKSON, WILLIAM H. SCHERMAN

MICHAEL J. DE SHERBININ '42

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

NOVEMBER 1927 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

December 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Tom Braden '40

October 1942 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

August 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPublic or Private Schools: A Letter to the Editor

MAY 1932 By Louis P. Benezet