ON the paneled walls of the great museum in Toronto are pictured the periods in our earth's geologic history when its crust was cooling, when great mountain ridges were pushed upward, when gigantic convulsions created new contours, ridges, valleys, oceans, and continents, when volcanoes blasted forth fire, steam and boiling lava. It was a lifeless time which terrifies our imagination.

In the columned pages of the newspapers of our time are pictured many phases of this current period of our world's history when the fires of war are still coolling, when the statesmen of the world are pushing each other for preference in the control of the deposits of the earth's resources and of the earth's people. And the people are confused. It is a time of life, and death, which challenges our imagination.

This is your period in time. In it the prejudices, the inherited and acquired bitternesses, the passions and hatreds, deeply rooted in men's minds, struggle for expression.

The mistakes of men, their misunderstandings, their misinterpretations of history, and their ignorance hang like heavy rusted chains on our arms and shoulders as we strive to build tomorrow's world.

You know, as well as I, the problems that must be solved before we know the answers that tell us of the future. Berlin, China, the Far East, the Near East and oil, Moscow, and millions of dissatisfied people who thought they saw in the defeat of Hitler's brown-shirts the promise of four freedoms—now bewildered, seem to have to choose between minimum economic security of totalitarianism and unwanted responsibility for the establishment of the freedoms which they believed would some-how be bestowed upon them. They, these millions, like us do not understand the nature of freedom. It cannot come as a gift. It cannot be bestowed. Freedom must be won, dearly purchased, and the price is responsibility.

We are, I believe, making progress—slow progress—you are no longer subject to the kind of influence described by a paragraph in the popular novel of a few years ago called The White Tower. In that tale an American bomber pilot lands in a small Swiss village and there he meets among others a French philosopher. In one of their conversations the Frenchman says to the American:

"There was a time when you were something else. An engineer, perhaps; a lawyer, a student, a journalist—it does not matter. You were young, hopeful, ambitious, your energies directed toward the things of the spirit and the mind. Then the war came—another war—the endless war. The world said to you suddenly, 'No, you are none of these things' you imagine yourself to be. You are a bomber pilot.' You used to be interested in literature and the arts, but no longer. It has taken you and changed you from a thinker into a tiny cog in its monstrous machinery. Oh, a very remarkable cog, I grant you —a very precise, ingenious, effective bit of mechanism. But a cog, none the less. And in the process what has happened? What has happened is that you are probably no longer a thinking, feeling man in the sense you once were. Your mind, perceptions and sensibilities have grown decadent and in danger of atrophy."

You have, I believe, made the transition back again. You have grasped the opportunity and completed the circle. You are not mere doers but thinkers, no longer agents of another's will but forces of your own, and responsible for your destiny.

The primary need of our society is for responsible citizens. The college that affords its students opportunity only to learn some science and a little history, to read the classics of literature, to taste a small portion of sociology, economics, and anthropology, to appreciate art and music, to examine philosophies and question theologies has only begun its proper function.

The great purpose of education is to help young men and women to become self-reliant, responsible citizens in a cooperative community. I am not at all sure that self-reliance and responsibility can be taught in the same sense that physics and history can be taught. Initiative, imagination, cooperation and responsibility can, however, be learned, given the environment of the academic community. He who spends four years in the presence of such an opportunity and does not learn to carry his citizen responsibilities, to cooperate with his fellow men in the maintenance of the commonweal, and to strive constantly for freedom under law, has failed in his proper educational purpose.

The Dartmouth, commenting recently concerning a particular issue in the life of the college, said a student who cannot learn to discipline himself "is likely to find himself on his way back home to break the news to mama that while he can behave himself when she is around to tell him what to do, when he must tell himself what to do, he is unable to do anything else but what he shouldn't." One of the chief purposes of education is the development of self-discipline—the substitution of self for mama; the substitution of self for ulterior authority in cooperative community.

This is the great need in American education, especially in our privately endowed colleges where the justification for their existence is dependent upon a higher output of responsible cooperative citizen leaders than might be expected of the great publicly supported state universities.

This need is our special responsibility. This is the opportunity that you have enjoyed.

There are two suggestions I could make to you as you mark the transition from learning to doing—from receiving to giving—from less to greater responsibility.

The first is that in your thoughts and in your actions you shall be radical. By that I mean no more nor less than the true meaning of the word. I once heard a judge of the Superior Court of one of our great mid-western states say that he wanted to be known as a radical—not a liberal, not a conservative, but as a radical—because he wanted always to be recognized as one who sought the roots of all problems—the roots of the issues of his time. He wanted to develop his opinions upon an understanding of basic and fundamental factors. He wanted to cut through the emotional over-layers which so often hide the truth, he wanted to be able to dig beneath the prejudices and stereotype opinions of other men and discover root causes.

In the midst of a vast surge of opinion concerning academic freedom, before the tides of prejudice concerning the many varying problems of racial relations, or in the confusions of attitudes concerning the choices of roads toward one world, we need men who can see clearly, understand thoroughly and choose wisely because they know the roots.

I suggest, although I know the analogy is not perfect, that it is the oceanographer who knows the long-range future of Europe and its culture, because he knows the deep currents of the oceans that control the climate that in such large measure controls the economic and cultural life of European people. So it is the anthropologist and the sociologist who knows best the long-range answers to some of the racial problems that vex American colleges today. These, like all our problems, will not be solved by men who study them through dark glasses of prejudice and expediency. Only with the microscope that helps us see the roots and the telescope that brings us into focus with the remote relations of justice and right can we know the answers.

That prompts my second suggestionthat you be religious. By that I do not mean that you must belong to any special ecclesiastical organization or that you be committed to any particular creed or dogma. Some of you either by volition or inheritance are—some are not. I do mean, however, that you shall because of the privilege that you have enjoyed and the responsibility that is yours, live in accord with a concept of religion which is not particular but, for the commonweal of tomorrow's world, is essential.

Each of us will find his own religion and his own way to celebrate his religion-some in loneliness pondering the great and ultimate mysteries, some in quiet communion with others in clean, white meeting houses, some in great cathedrals where color, music, and incense motivate their aspirations.

All of us shall need a sense of belonging to Something bigger than ourselves—and a pattern and method of relating ourselves to that Something. This pattern and this method can be our religion. For religion is the light by which we see the right and the wrong. Religion is the warmth which makes us feel our kinship with all men everywhere. Religion is the way we think about ourselves and others. Religion is the anchor chain which holds us fast to our ideals, when tides of disappointment would sweep us out upon a fog-covered ocean of despair. Religion is the telescope by which we measure the distances from ourselves to the shining stars of our perfection. Religion is the firm, strong grasp with which we may hold in our two hands the issues of our day, tear off and cast away the shabby crust of evil, and hold aloft for men to follow the elements of good. Religion is the pattern of our lives that gives us a sense of belonging, of participating, an urge to cooperate to better the common welfare of mankind.

To Dartmouth, your college, my college, we know we belong. We are members of the Dartmouth family. We feel the obligations and the privileges of that relationship. It is to the extension of the ideas and ideals of this relationship to the world of our tomorrows that we commit ourselves this morning.

We are all members of families—many are gathered here with us today. We understand the ideals of families. We know what they are for. Some of you already know what your mothers and fathers know, that families are for learning joy, the joy of young voices in laughter, the joy of first questions and the searching together for answers. The joy of confidence and trust and understanding that bind old and middle-aged and young together in some place called home.

Families are for learning the give and take of sharing not only things like cars and clothes, but chores, responsibilities, duties and feelings. Families are for building attitudes so necessary for living together in community.

Families are for learning how to meet and know sorrow and tragedy. Families are for comfort and consolation, for facing tomorrow when death calls today.

Families are for Thanksgiving and Christmas and summer vacations and for all the long days of the seasons in between. For bearing the loneliness of long separations, the hardships of disappointment and the anxieties and fears that time and distance make so real.

Families are for holidays, birthdays, anniversaries and commencements—families are for every day—so that people growing up may learn what it is to belong to something bigger than just themselves, something to which, if they give themselves, they can take more than they will ever need.

To such a family we belong. Dartmouth has given us all the opportunity to develop free minds—free minds with which to search—perchance to find new truth, free minds which need never cower before human opinion, free minds which shall guard their empire of integrity as nobler than the empire of the world.

It is from this family—its hearthfires and its brotherhood that we go this day upon our several ways.

May the ideas and the ideals, the ambitions and the loyalties, the courage and the convictions that we have here learned prompt our thinking, prod our planning and guide our living wherever we may be tomorrow and tomorrow and always.

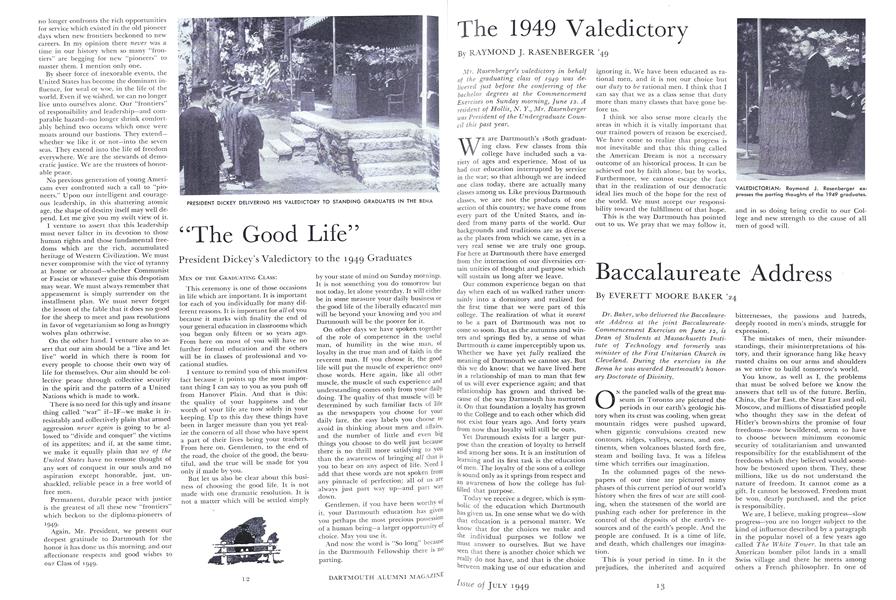

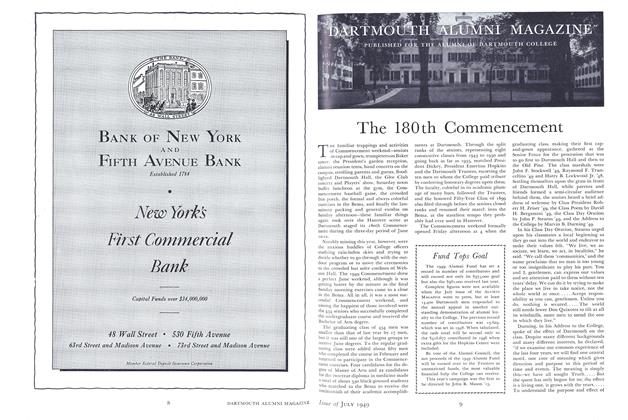

BACCALAUREATE SPEAKER IN ANOTHER COMMENCEMENT ROLE: Dr. Everett M. Baker '24 (left), Dean of Students at M.1.T., as President of the General Alumni Association presided over the meeting of alumni, faculty and seniors June 11. He is shown with Dr. Dickey who also spoke at the meeting.

Dr. Baker, who delivered the Baccalaureate Address at the joint BaccalaureateCommencement Exercises on June 12, isDean of Students at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and formerly wasminister of the First Unitarian Church inCleveland. During the exercises in theBema he was awarded Dartmouth's honorary Doctorate of Divinity.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1929 Sets Record at 20th

July 1949 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES '29, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930 Holds Advanced 20th

July 1949 By ALEX J. McFARLAND, -

Class Notes

Class NotesA Memorable 45th for 1904

July 1949 By DAVID S. AUSTIN II '04, -

Article

ArticleThe 180th Commencement

July 1949 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1939's Tremendous Tenth

July 1949 By CLEMENT F. BURNAP '39, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924's Big Twenty-Fifth

July 1949 By C. N. ALLEN '24