As Vice President of NBC in Charge of Television, Pat Weaver '30 Is Steering a Giant Social Force

IT WAS 6:37 P.M. on a dark spring evening when lanky Pat Weaver telephoned his wife, waiting at home. One foot was pointed toward the door of his sixth-floor office in Radio City. The other was planted squarely in the middle of a sorely-tested swivel chair.

"Don't run!" he instructed, a little breathless. "Weil leave for dinner in ten minutes."

This typified a daily race against time by the 41-year-Old, six-foot-three Dartmouth graduate who is now Vice President in Charge of Television for the National Broadcasting Company. All he had left on his day's schedule was a 7 p.m. dinner with David Werblin, radio-television vice president of the Music Corporation of America, the country's largest talent agency, and an 8:45 p.m. curtain at the Plymouth Theater for The Happy Time, a sprightly family comedy which MCA was suggesting as the basis for a new NBC television series.

Tireless and ebullient, Sylvester Laflin Weaver Jr. '30 finds himself today at the whirling center of a new industry which is likely to change the social pattern of the United States as decisively as did the automobile, the telephone and the atom bomb. Among the scientists, businessmen and artists who already have brought television to nearly 6,000,000 homes in the country, he is responsible for directing and developing the semi-autonomous television operation of NBC. Upon such young men as he largely rests the direction which television will take in the next few years, affecting movies, theater, publishing, public opinion, education and home life. By 1955, the impress of the new medium will be titanic on all phases of life as we know it now. An estimated 25,000,000 homes will be reached by the television network of NBC alone—some 80,000,000 people.

It is a lively study, therefore, to consider Weaver, his personality and experience, and his views on the shape of things to come.

When he and his wife, the former actress Elizabeth Inglis, returned to their six-room apartment on Manhattan's East 64th Street around midnight on this typical day, 1950 T.V., some 14 hours had passed since he had joked at the staff meeting which started his Tuesday routine: "I'm so tired I have to check this morning to see what really went on last night." He was referring to his session at home, eating from a tray in the living room before a television set and later reclining in the bedroom in front of a second set, watching nearly three hours of the Monday night programming on the network.

At 10:15 a.m., with his feet on the desk, Weaver had brought the meeting of his staff executives to order. He first led a brief and informal discussion of possible commercial themes which Emerson Radio and Television might employ on TheClock, a mystery and suspense show which they had decided to sponsor on NBC. Then he came to the point of the meeting with a bit of hyperbole, which caused the other seven men to smile.

"I had a sleepless night," he said, not meaning it. "But I finally made up my mind about our Saturday Night Revue (the two-and-a-half-hour musical variety show which is supervised for NBC by genial producer George McGarrett '29). Since this is a democracy, I want you people to have a say, too!"

On this cue, the executives from Program, Production, Sales and Engineering examined all aspects of taking the elaborate program off the network for the summer. Nub of the problem was that sponsors hadn't bought out the available time and that the creative efforts of the production staff were being stretched to a breaking point.

"Saturday Night wasn't supposed to be so good," Weaver said at one point. "We designed the form for new talent in order to maintain the production week after week so that the small advertisers could get on the television bandwagon. But this is too good! Our artists are killing themselves. The show is better than a Broadway revue."

During the course of the meeting, Weaver, who doesn't smoke, frequently popped a Life Saver into his mouth. He showed no annoyance as other men in the room arose and helped themselves from the package, which was emptied when the session came to a close at 11:55 a.m. It had been decided to recommend to the Radio Corporation of America, NBC's parent company, that the show be given a summer hiatus, the opinion that Weaver had arrived at the night before.

At 12 noon, his day now guided closely by the little black book maintained by Ellie Gallagher, his secretary, he was closeted for 45 minutes with Robert Sarnoff, head of NBC package sales. At 12:45 p.m., he met with Francis McCall, news and special events chief, and gave final approval to the telecasting of a series of horse races on the network during spring and summer. At 12:54 p.m., he took his first look at the mail and accomplished five minutes of dictation before he left at 1:10 p.m. for lunch in the NBC dining room with Niles Trammell, chairman of the board.

At 2:30 p.m., he conferred with Robert Mann, a writer-producer on a projected series. At 3:10 p.m. after another ten minutes of mail and dictation, he had a 50-minute meeting with Chick Showerman, NBC vice president visiting from Chicago, mainly on the sales approach to the Saturday Night Revue. With only occasional assistance from Robert MacFayden, director of TV research, who joined the conference, Weaver neatly projected the comparative audience figures of television and key magazines, and succeeded in firing the enthusiasm for the high circulation of the top program come fall. At 4 p.m., he relaxed briefly with the writer who was interviewing him, and at 4:17 p.m. he left for the 53rd floor of the RCA Building, where he had a planning session scheduled with Ron Lewis, RCA budget director and member of a special future plans group.

This confidential, high-level meeting lasted until 5:50 p.m., more than an hour and a half, without a break. Returning to his own office, he took up the day's memoranda, each boiled down to a few lines on a small white sheet of paper. These he discussed with Fred Wile, television produc- tion director, his virtual assistant at NBC and a close associate since 1934 when they met at Young & Rubicam. The day's late decisions were made, covering such dissimilar subjects as a new contract with comedian Sid Caesar and engineering plans for additional television space.

At 6:37 p.m. when he called his wife, as noted previously, Wile was still with him, and they left together, still talking. Time: 6:40 p.m. twenty minutes before his dinner engagement with the MCA vice president.

IF there is a touch of the frenetic in this recount of one day's schedule, it is cumulative, rather than actual. Despite the crisis atmosphere in which television operates today, Pat Weaver is steady, constantly refreshing himself and others with a bright sense of humor. He uses the stilleto cane, a gift from the legal department, only in mock desperation. He has time for appreciation of what television has accomplished and what it may do in the years ahead. He is willing, being forwardlooking, to turn the iconoscope's shiny face into a crystal ball.

Weaver foresees television, with its daily potential of 80,000,000 viewers in 1955, as the giant of the entertainment business. He sees it replacing the domination of the movies, on the one hand, and revivifying the legitimate theater on the other.

"Television's effect on the motion picture industry will be profound," he says. "Volume and profit will be materially reduced, and fewer, finer films will be produced for theater audiences. This effect will follow for the simple reason that most pictures rest their appeal on stories. Stories are now offered by television just as interestingly as in theaters, and at no cost.

"Movies will concentrate on really fine films which have their appeal in the artist's performance, great story value, emphasis on spectacle, flexibility, perfectionism, or in some intangible which needs the presence of people together in the theater to enjoy it. Theater showings of film will continue so long as the movies maintain their wonderful scope of illusion and people want to leave their homes to be entertained in a group."

Weaver anticipates that legitimate theaters will be strengthened by the interest which television creates in the seven arts. It is even likely during the years to come, he thinks, that shows, especially revues, will find it wise to pre-test their programs in theaters and that, after the long run, legitimate shows will finally be presented to the vast television audience.

Concerning color television, he is, of course, a supporter of the compatible system which, is now in its advance research stage in the RCA laboratories. This method depends on color projection through the tube itself, rather than the CBS development of projection through a mechanical system.

Color television will come to the homes, but at this writing, the FCC has not ruled on the prevailing system. At any rate, Weaver does not see any large-scale use of home color receivers for three, possibly five, years. Even when it comes, he doesn't believe all programs will be televised in color. Because of the tremendous expense for color programs (black-and-white major TV production budgets for shows like the Philco Television Playhouse and Texaco Star Theater now average $20,000 weekly, exclusive of time charges), he thinks that the home audience may be sent the color shows in the selected way Hollywood now issues a limited number of Technicolor films.

Most important in Weaver's thinking is his conviction that television will be the largest single factor in shaping American public opinion.

Unlike those who grieve over the impact of television as a mass medium and see every receiver as a living-room lodestone to mental ruin and social atrophy, Pat Weaver views television as a mark of civilization's progress. He is not a mere pragmatist, thinking it good because it works. He evaluates television as a humanist. He firmly believes it will be a force for the good.

"The real meaning of contemporary civilization will become clearer to all of us through television," he states. Television will be the living-room instrument that makes contemporary civilization, in all its vastness, a part of the life of every man.

"Television will become the powerful social force around which future habits and future ways of life will be built. For the first time, the average man will find himself a participant in the world of his own time.

"He will see his political leaders, meet with them at their important conferences, sit behind them at their bargaining tables. He will see all the great musicians and other artists of his time. He will see literary figures, and he will take part, at least as an observer, in the debates of the articulate elite who are attempting to lead public opinion.

"Just by being exposed to varied entertainment, which will be the base of attrac- tion in keeping the instrument a vital factor in the living-room and bedroom of the home, the average man will develop an inquiring mind and be more interested in the world around him. He will not only find stimulus to entertain himself but he will be encouraged by example to advance himself."

These remarks, made in the privacy of his apartment at a desk flanked by volumes of history, philosophy and classical studies, are not little valentines for mailing to the Federal Communications Commission and summer seminars of our professors. They are the beliefs of a restless man who has spent 18 years of his life translating ideas into patterns of words and pictures to arrest masses of people in their homes.

Onetime writer, radio producer and advertising director of the American Tobacco Company under George Washington Hill, Weaver has risen to his present position of influence through the volatile yet hardheaded business of attracting the attention of people so that they may be sold an idea, usually an item of commerce. He may be modest but he is not embarrassed before the image of an advertiser who is entertaining and educating millions of consumers.

He is optimistic about television as a business and advertising medium:

"It will be immensely profitable to stockholders. As an advertising-supported medium, it will have tremendous influence on the entire means of distributing goods in the American economy. It will develop effective means of selling goods and services and therefore will lower the cost of distributing the goods themselves. By exposing people to the possible advantages of a broader, richer life, television will, in the American tradition, constantly increase the desires and needs of the American family."

His thought that advertising will continue to raise the living standards of the country is not original. It is, however, the mainspring of his conviction and those of his colleagues that advertising is an eminently better sponsor of network radio and television than government. Private broadcasting means freedom to succeed or fail in supplying the home audience with programs that both entertain and illuminate.

"Obviously," he says, "anyone who has worked through the private enterprise system and believes in it, looks with abhorrence on government direction of anything which has to do with the shaping of opinion in the American people."

This is not to say that he refuses to acknowledge the government's interest in the medium. Frequently in his speeches, he has referred to the amazing efficiency with which both radio and television can deliver the entire country to the service of government in time of national emergency. In addition, he respects the FCC as an impartial body for the regulation of the technical aspects of the business.

The National Broadcasting Company, as the largest of the existing television networks, is plumb center in whatever circle of cause and effect is drawn by the television revolution. Pat Weaver will be bound by the circle, too, with all his background and growing experience in the field called upon to assess the damage and progress. Some magazine and newspaper publishers, whose circulation figures may wane in a few years, may join the unhappy groups in Hollywood. They will point to television as the robber of their advertising income.

The failings of parents in controlling the viewing habits of their children will be laid before the TV stoop, and proponents of a hundred other activities soon to be affected severely by the new home medium will shout maledictions against the television operators. Another generation will be spawned across the coaxial cable-marked country before the revolution will ebb and leave us another, different version of the status quo.

PAT springs from the radio generation himself, a connection he believes he is continuing by remaining with what he calls the home entertainment media. The eldest of four children, he was born in Los Angeles, Dec. 21, 1908, and raised in Fremont Place with one sister who is now fashion editor of the Hollywood Citizen; another who is married to a Los Angeles attorney; and a brother, "Doodles" Weaver, well-known comedian who plays any or all instruments in the Spike Jones aggregation.

His father, a pioneer civic leader in California, was owner of Weaver-Henry Corporation, a roofing manufacturing firm, which he sold out to Johns Manville the summer before the crash of 1929. Mr. Weaver, Senior, as befits an ex-president of the Chamber of Commerce and Founder of the All-Year Club of California, is still dubious of his son's eastward trek but takes great interest in his career. Mrs. Weaver died in 1939.

Pat graduated from L.A. High in 1926 (he still wears a society ring from the school). He entered Dartmouth with the Class of 1930, eventually majoring in Philosophy, with minors in Classical Civilization and Psychology. He remembers with fondness Professors Urban, Nemiah, Stone, Allport and many others. "The classical civilization studies were the most enjoyable for me," he says. "It was a matter of real regret for me then—and particularly later when I travelled around the Mediterranean looking at ruins—that I hadn't done preliminary language study so that I could have made a career out of classical civilization."

As a Dartmouth student, however, Weaver did well. He was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, won "some sort of prize in philosophy," and graduated magna cum laude. He was manager of the tennis team and went out for freshman swimming, but gave up the sport when, after practice one afternoon, he walked from the warm gym into zero weather and, a day later, into Dick's House. "My most important extracurricular activities," he recalls off-hand, "were making the Montreal and Bermuda runs as often as possible and skiing."

He also studied short-story writing and was a member of The Players. "I wanted to be a writer because I felt that was the way I could keep moving and earn large amounts of money at the same time. I thought that writing would be a very nice way to make several million dollars in a hurry and without getting too tied up in the process.

"I felt it would be a good thing, in a money economy, to specialize in money. Not only in how to get it, but particularly in how to make money do the work for me instead of having to make the money myself. Although I was absolutely right in this strategy, I've never been able to get around to it. I find myself still making money instead of money working for me!"

At any rate, optimistic, aggressive and, in his own words, reasonably happy in 1930, Weaver returned from his postgraduation trip around the ruined shrines of ancient civilizations to try his luck in depression-ridden New York. He started selling magazines, "for experience while I tried to sell fiction," but when he failed to sell any Journals or Companions in a month and chose not to clinch a job as writer for Time, he went home to L.A. He took a job with Young & McAllister, a direct mail and printing firm, as writer and salesman. A year later, 1932, he joined the Don Lee radio network as a script writer.

First script by the philosophy student was a semi-inspirational documentary series, America Victorious, on great depressions in history. Things became more cheerful thereafter, and Weaver soon found himself inventing gags for comedians, dialogues for crooners, and reportage for commentators. Before long, he was producer of The Merrymakers, Happy GoLucky Hour, and California Melodies among some 150 other shows he worked on during his three years on the coast.

It was while with Don Lee in 1933 that he first became acquainted with television, the network having erected one of the first experimental stations in the country. Radio was the growing industry, however, and although he foretold TV's future at the time, Weaver's star was hitched to America's newest mass medium, the coast-to-coast radio show. Except for a brief flirtation with the movies as an actor, in which he uttered an eloquent "Ugh" in the role of a Zulu during a film being shot in Catalina, he prospered with Don Lee and its affiliation with CBS. In 1934' was appointed program manager of KFRC in San Francisco.

One memory that stands out during this period is the audition which he wrote for a rising singer, Bing Crosby. Until that time, only Crosby's romantic dulcetness was known to America. Weaver s idea for the audition was that the singer could also talk, make jokes, and smoothly emcee his own program. The sponsor, Woodbury Soap, heard the try-out platter and promptly decided that Crosby's place in entertainment was limited to warbling. "Their feeling was that he couldn't talk,' Pat explains without further comment.

The KFRC band and station staff serenaded Weaver when he left San Francisco for his second try at New York in June of 1935. Six weeks after his arrival, with the help of the CBS Artists Bureau, he had parlayed his talents into writer, producer, emcee and account executive of the IshamJones Revue, a network show sponsored by the United Cigar Stores and Whelan Drug Co. He took the account to Young & Rubicam, an advertising agency then growing rich on radio's zooming popu- larity, and before the first snow of the year, was hired by Y & R to produce the Fred Allen show.

Within two years, he was the agency's number two man, director of the radio department, the fulcrum of a burgeoning business. This position led to the American Tobbaco Company in 1938. He was hired, at the age of 30, to advise George Washington Hill on radio matters, but by the time he was 31, he was appointed the firm's advertising manager, Hill's righthand man.

Weaver had strong feelings about Hitler several years before the mustached dictator embroiled Europe in war in 1939. He joined groups urging America to interest itself in European affairs, made speeches denouncing Hitler's politics, and busied himself in developing public opinion to support American intervention. Then, in 1941, suiting action to words, he sought to enlist in the Navy. At the urging of Nelson Rockefeller, a college classmate, he became instead radio director of the Office of Inter-American Affairs.

In 1942, he was called to active duty in the Navy, and took his indoctrination course at Princeton. By 1944, before he was transferred to executive producer of the Armed Forces Radio Network headquartered in Hollywood, he had spent 18 months at sea, the last year as skipper of an escort vessel in the South Atlantic's "Torpedo Junction." The Navy called the sub chaser PC492, but the crew, presenting Pat with a portrait of the ship, called it El Diablo Loco or Weaver's Folly.

His sea duty was occasionally tense. German subs exacted a terrifying toll in the area. But the long voyages had a certain monotony, and he put his portable to woik again. He wrote a novel, still unpublished, The Journal of John Jason James. He describes it in terms of Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward. It is the story of what a sea-going philosopher finds when he returns to America after 25 years' absence. Needless to say, passages of the wartime book show that television is the country's paramount means of communication and entertainment.

Weaver returned to the American Tobacco Company after the war, then went back to Young & Rubicam as vice presi- dent in charge o£ radio and television. RCA and NBC won him away from this position in the summer of 1949.

PAT left his bachelorhood at Great Neck, Long Island, on Jan. 23, 1942, when he married the beautiful and talented Elizabeth Inglis. The brunette actress had come to the United States in 1939 to appear in the broadway production of Gaslight and Shubert's presentation of BillyDraws a Horse, in which she played the ingenue part opposite Arthur Margetson. She was immediately snapped up by Hollywood, but retired soon after her marriage.

The couple went to the Hollywood Public Library to select the name of their first-born, a boy, whose birth occurred October 20, 1945. They christened him Trajan Victor Charles; he is now four and a half years old. strongly resembling his father. A girl, born October 8, was named Susan Alexandra, another name with classical overtones.

Under the new pressures of television, and with a second child, the Weaver family life has not settled into a pattern. This year was the first since the war that Pat was not able to take his usual 30-day vacation, a respite he regards as both reward and necessity. "It is the one point on which the Board should be over-ruled," he laughs. Nevertheless, he forewent his month's leave this winter in order to concentrate on network plans built around the successful Saturday Night Revue. He did manage ten days of skiing near Zurich in Switzerland and a few days at Mad River. His wife plans to encourage his tennis playing this spring and summer, as well as frequent visits to their newly bought farm in Maryland. Mrs. Weaver, who, incidentally, has cajoled a succession of secretaries into prohibiting Pat from ordering cold lunches at his office desk, feels that her husband should slow his pace from the 18-hour grinds and seven-day weeks which have marked his career.

Whatever his routine at present, his appearance is one of boundless health, and his evident energy does not rise from hyper-tension, for he is seldom without his froth of humor. He neither drinks nor smokes, the twin habits of "J- Ulcer Yes, the Dean of Agencymen," a caricature created by Pat himself in public speeches.

He is an excellent speechmaker. He eschews jokes of the convention type, but gets heavy laughs through innuendo and travesty, even at his own expense. Dartmouth classmates who remember his memorial fund auctioneering at the 20th reunion, will understand this quality. His speeches are marked, too, by references to philosophy. He will talk of an advertising campaign in terms of pragmatism, and will urge action for the sake of humanism. "There has got to be meaning somewhere, not just profit," he concludes.

As he told a recent Detroit meeting: "A man born near Hollywood, who rode to college on the Santa Fe before it even got appointed Chief, let alone Super Chief, I find the term huckster nerve-wracking. I trust I am too big a man to let the additional fact of my nine years' tenure as advertising director of the American Tobacco Company make any difference to me! But I personally feel that one of the things that holds all of us back is taking ourselves and our work too seriously.

"While I heartily believe that there is no company, and no group of companies in the United States with as able a line-up of executives as some of the major agencies, nonetheless, I see no reason to invest dignity in advertising offices, or any other, that does not naturally emerge from the human beings who occupy them."

"My artistic desire," he explains in a personal note, "is so intermingled with business knowledge and business desire that I find myself in a dilemma. I really feel that commercial arts such as television, radio and motion pictures are run by men who are essentially frustrated artists.

"If we were better writers, we probably wouldn't be in the business end of writing. If we were better at any of the real arts, we probably would say to hell with the rewards and live as artists. If we were straight business men, we wouldn't have all the trouble that comes from the artistic tension of any creative life. It's all very sad," he observes, "and I often wonder, as my artists fawn on me and I sit counting my money, how I stand it."

So there is something basically humble in Pat Weaver, despite or because of his sharp humor. Somewhere, he has learned his lessons well. He obviously feels that the business man can help the artist—the philosopher and the educator—bring reason and beauty to the marketplace in which most of us find ourselves.

It is a curious combination to examine in a midwife at television's birth, but an encouraging one.

Clarifying his own thoughts recently in a closely-typed, 19-page memo to his staff, he wrote: "If we can have a vigorous spirit of rightness in what we do, a sense of being a part of a good, proper, resultful and helpful development in our society, we will have security in our beliefs.

"We need not question the important and valuable contribution we can make to our society in the development of television as a social instrument. Since we live in a time of troubles, of pervasive insecurity and psychological unrest, it is important that we take pleasure and pride in our work. We can make a contribution which will outlast us and measurably augment the artistic or economic or social potentialities of television and our times."

The man is trying to combine a sense of history with his proven business sense. He wants to keep the horse before the cart.

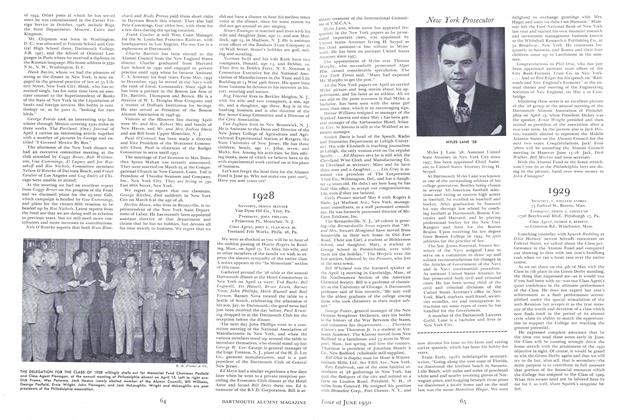

ON THE JOB: Sylvester L. (Pat) Weaver '30 at his office desk in the RCA Building, New York.

TRANSMISSION TOWER, atop the Empire State Building, which sends forth major video shows.

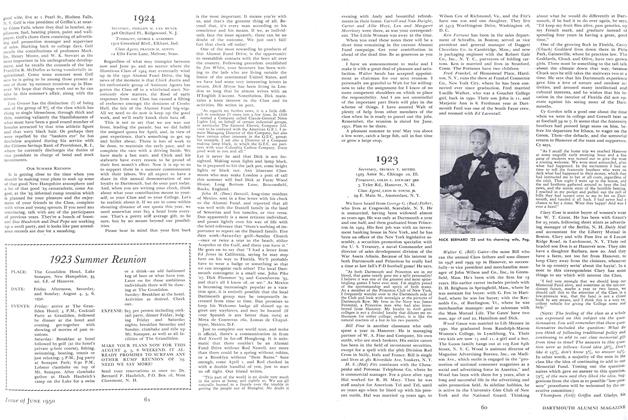

THE WEAVERS AT HOME: Shown in their Manhattan apartment are Mrs. Weaver, the former Desiree Hawkins of Colchester, England; Susan Alexandra, who will be one year old in October; Pat Weaver; and Trajan Victor Charles, who will be five in October. Pat's ardent interest in civilization shows in the choice of names for the children.

A TELEVISION CONTROL ROOM REQUIRES MULTIPLE HANDS, EYES AND EARS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

June 1950 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

June 1950 By ROBERT C. BANKART, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR., ALAN W. BRYANT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

June 1950 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART 3RD, LEON H. YOUNG JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1916

June 1950 By CMDR. F. STIRLING WILSON, DANIEL S. DINSMOOR, WILLIAM H. MCKENZIE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

June 1950 By WILLIAM H. HAM, MORTON C. TUTTLE

ROBERT R. RODGERS '42

-

Article

ArticleCARPENTER GALLERIES ATTRACT WIDE INTEREST

November 1940 By Robert R. Rodgers '42 -

Article

ArticleJANITOR'S LIFE

December 1940 By ROBERT R. RODGERS '42 -

Article

ArticleGALLERIES SPONSOR DESIGN DECADE SHOW

December 1940 By Robert R. Rodgers '42 -

Article

ArticleTONY THE BARBER

May 1941 By Robert R. Rodgers '42 -

Article

ArticleYankee Progress and Ingenuity

December 1941 By Robert R. Rodgers '42 -

Article

ArticleNuremberg Club

February 1946 By Robert R. Rodgers '42

Article

-

Article

Article1960 Alumni Fund

January 1960 -

Article

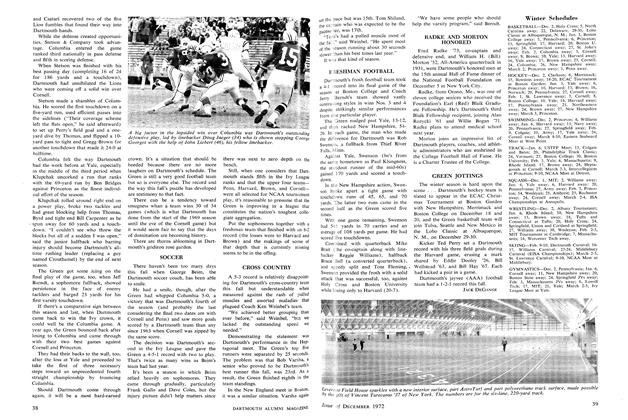

ArticleWinter Schedules

DECEMBER 1972 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1985 -

Article

ArticleA penny saved . . .

MAY • 1987 -

Article

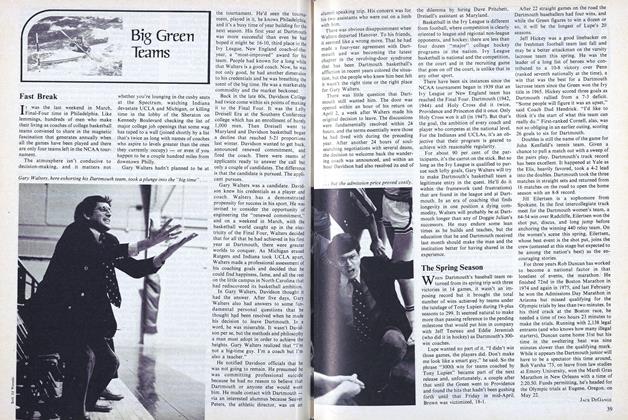

ArticleThe Spring Season

May 1976 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleClassical Art From Ancient Shipwrecks

December, 1928 By Professor William Stuart Messer