BILL O'NEILL, driving a one-horse buggy along Main Street in the winter of 1913, saw Harry Wells stamping over the snow on the sidewalks.

"Mr. Wells!" Bill shouted. "Can you use a good janitor?"

He didn't waste any words. He knew Harry, and Harry had known him for almost four years as one of the best drivers in the Hanover Livery Stables. Bill had often taken him to the station at White River Junction in one of those bouncing Concord coaches or in the swift surreys. The road was still dirt: a quagmire in the winter and a billow of dust during the hot weather.

"Sorry, no jobs now," Harry answered, kindly. There were more than two hundred men on the waiting list.

But three months later Bill O'Neill began his Dartmouth experience as janitor in Middle Mass, and three years later he was appointed head janitor in the Gym, the beginning of twenty-four years personal contact and intimate concern with Big Green athletics. Whitey Fuller recently said that a team's success or failure could be judged by Bill's mood.

LIVES IN FIELD HOUSE

He remembers the players, their names, and their locker-room banter. He has lived for fourteen years in a two-room apartment next to the eight showers on the second floor of Davis Field House. Above him are the forty beds for visiting teams. Below him and near him are the equipment rooms, the locker-rooms, more showers, offices of coaches, the Trophy Room, and all the other paraphernalia of Dartmouth athletics.

Outside, near enough to hear from his room the wise-cracks and barking of the coaches, are the practice fields, the baseball diamond, and the stadium; and the basketball, squash and handball courts virtually surround him. He is seldom away from the thudding sound of balls.

Yet Bill O'Neill has never played a game in his life. Educated in White River, he played neither baseball or hockey, the popular sports at his high-school. "I was never big and rugged," he explains.

Today, at sixty, in active health, he smiles and says, simply, seeing the humor in the position of a man who is surrounded by the athletic environment but who has never played a game in his life, "Well, there's this about it: It keeps you from feeling old."

And Bill, besides his vigor and the downright respect of the men working with him, has his memories. "I'm not much good at telling yarns," he protests. "People are always asking me who is the best athlete, which was the best team, and things like that. You're the first to ask me who was the worst athlete!" But a man that remembers names and dates, he described much that was outstanding in Dartmouth history.

"The best all-around athlete I've seen was Jim Robertson. Why, Jim wasn't only captain of both the football and baseball teams for two years straight. In the spring of 1919, he almost broke the college javelin record when he wasn't even on the track team! He was working out on the baseball field one afternoon and near the end of the practise strolled over to the track, picked up a javelin just for fun, and threw it within four inches of the record mark!

"Jim was also playing in the backfield in the most exciting football game I've ever seen in Hanover. Youngstrom, Sonnenberg, Neely and Cunningham were on the team then. The opponent was Colgate.

"It was a bad day for the game. Rain and splashing mud a foot deep. We tried to make the footing for the boys better by spreading hay all around but it was still bad.

"At the end of the first half, Colgate led us 7 to 0, and the boys were pretty low. They came into the locker-room wet, dirty and discouraged. They had fought hard. Fats Spears tried to cheer them up, but he didn't have much success.

"Major Cavanaugh, who had left Dartmouth the year before to coach someplace else, asked Fats if he could say a word to the team. He didn't have any time to talk, but in a few minutes he had changed the whole spirit. He got the boys joking, and by the time they were on the field, they were a completely changed outfit.

"Colgate couldn't get any place the next half. Not only were they held, but Dartmouth smothered them, pushed them back, and held them close to their own goal line.

"Finally, in the last seconds of the game, Swede Youngstrom made the break. Colgate had been shoved inside their own twenty, and were going to kick out. Swede tore through the line in that terrific charging way of his, pawed the ball down, and then lunged for it and recovered in the end zone. The score was 7-6, still Colgate.

"There were only seconds to go in the game, and in those days the point after goal had to be made within the limits of the period. All of us on the sidelines were breaking our hearts. Robertson came through for us. He kicked the damn ball through the posts and out of the field!"

Those are the great days of Bill's memories. Today—he has trouble finding words to describe the change—the players seem different. They practice more and they are supposed to be bigger and faster, yet, somehow—"Well, I don't know exactly how to say it, but the others seemed to me to be tougher, more rugged. Not so much temperament as now. They played for fun and they played it rough."

Bill nominated F Fas the worst athlete he has ever seen. He laughed when he thought of him and showed his respect for the boy who wanted to pitch, who couldn't pitch but still wanted to pitch for the varsity. "Jeff used to kid him a lot," Bill said. "F would strike out everyone in practise, not knowing that the players were letting him do it. F was a grand kid, though. Nothing got him down."

PHILOSOPHIC ABOUT GYM JOB

Keeping the Gym in shape isn't much of a job for Bill. The hurricane blew in a window on the south side, it leaks during the rainy season, he is always finding balls in odd places, the baseball team breaks more than a dozen windows a season in indoor practise, but it's all in a day's work, and he's philosophic about it —"That's what we're paid for."

Occasionally something unusual happens. A few years ago, a student who didn't have a room on campus sneaked into the Gym and stayed there over night, sleeping under the old board track. He had been doing this for more than a week, when Bill discovered him one morning. The boy had overslept and didn't climb out the window before the staff went to work!

While football, hockey and baseball claim the major interest of Bill O'Neill he enjoys basketball, and he tells one of his best stories about a Cornell-Dartmouth game almost not played two decades ago. And then played in the only Sunday contest of college history.

Another of the usual New Hampshire blizzards had kept the Cornell basketball team from starting the game at 8:30, Saturday evening. The roads were blocked, Cornell hadn't shown up by eleven thirty the crowd still remained. "At ten minutes to twelve, the manager of the team said if Cornell didn't show up by midnight the contest would be called off, as no games were allowed on Sunday.

A student kept turning the clock back so that the hands never pointed to twelve o'clock! No one was fooled, but it did keep things legal, and when Cornell did showup, the game went on and was actually finished about two thirty Sunday morning. Bill didn't mind working late.

BILL O'NEILL

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleClassicist Not Without Honor

February 1941 By Donald Bartlett '24 -

Article

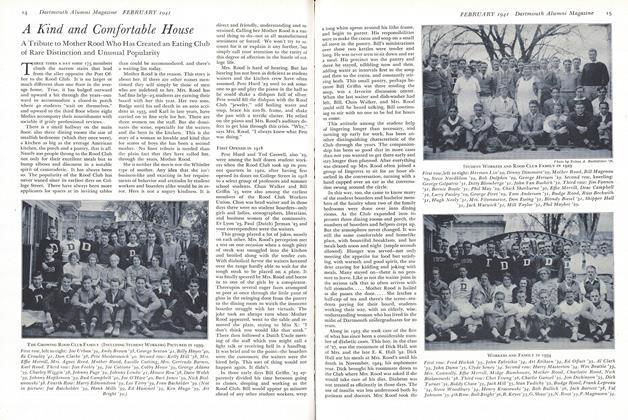

ArticleA Kind and Comfortable House

February 1941 By S. C. H. -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1941 By Charles Bolte '41 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924*

February 1941 By ALFRED A. ADAMS JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1939*

February 1941 By ROBERT W. GIBSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

February 1941 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR.

Robert R. Rodgers '42

-

Article

ArticleCARPENTER GALLERIES ATTRACT WIDE INTEREST

November 1940 By Robert R. Rodgers '42 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH BACK TO THE LAND

November 1940 By Robert R. Rodgers '42 -

Article

ArticleGALLERIES SPONSOR DESIGN DECADE SHOW

December 1940 By Robert R. Rodgers '42 -

Sports

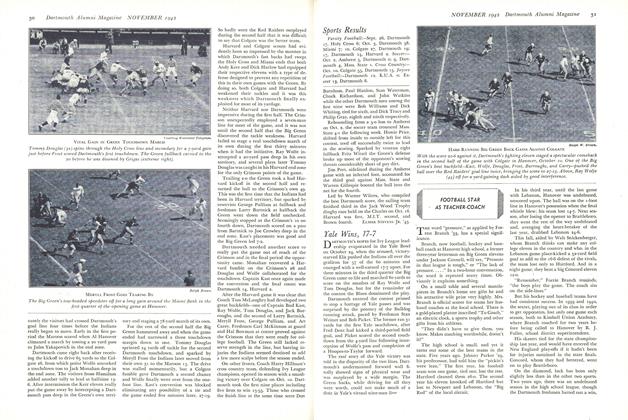

SportsFOOTBALL STAR AS TEACHER-COACH

November 1942 By Robert r. Rodgers '42 -

Article

ArticleNuremberg Club

February 1946 By Robert R. Rodgers '42 -

Article

ArticleTop Television Man

June 1950 By ROBERT R. RODGERS '42

Article

-

Article

ArticleBASEBALL

JUNE 1906 -

Article

ArticlePENN WINS AGAIN

June, 1909 -

Article

ArticlePay-As-You-Go Taxation

October 1942 By BEARDSLEY RUML '15 -

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago .... The Old Familiar Faces

April 1934 By Bill Mccarter 'l9. -

Article

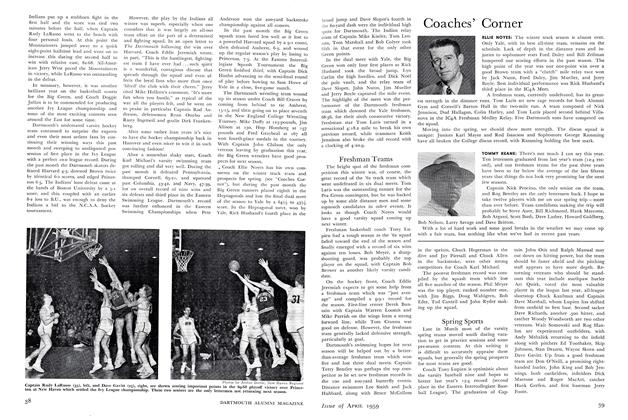

ArticleFreshman Teams

APRIL 1959 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleGreen Jottings

October 1961 By DAVE ORR '57