Research by Faculty, Ranging Over Divers Fields, Doesn't Allow That "12-Hour Week"

ONCE A DARTMOUTH MAN, never a city man."

The College sows in loyal hearts a seed of nostalgia which usually begins to bud on honeymoons at the Hanover Inn and to come to flower in men's for- ties and fifties.

Graduates would love to retire early and live in Hanover, do some part-time teaching and perhaps a spot of research. They would enjoy relaxing, using the hills as reclining chairs and the Connecti- cut River and the athletic fields as their favorite views. Thus they could benefit the College and themselves.

"It's good, the life you live up here," they say to their friends the professors on whom they are calling at what they hope is cocktail time on a football week end. "I envy you leading your quiet lives away from the terrible pressure of long hours and competitive business."

If the hills of New. Hampshire seem greener to alumni, so do the incomes of the alumni to the faculty. With limited information both often talk at cross pur- poses about each other's ultimate satis- factions in pleasure and work. To many alumni professors often seem relaxed and contented as if they had not a care in the world beyond meeting a 9 o'clock class.

If truth be told, the situation is differ- ent, for most men on the faculty, intel- lectually and emotionally starved by what they feed on, are restlessly unhappy if they are kept away long from their par- ticular fields of learning. They dread boredom and must always be working away at something. A businessman might call his pursuit outside his office a hobby; a professor calls his, outside his classroom, research.

Most of the alumni have a pretty good understanding about the industry and the scholarly production of older members of the faculty; they have not about the eager- ness and the struggle for publication among the younger. These newcomers, relatively unknown to graduates more than ten years out, spend long hours in preparation for courses. They want to prove themselves worthy of Dartmouth's traditions in teaching and scholarship. Though the College is full of these aspir- ing men of early middle age, the limited space for this article makes it necessary to tell the story of all of them by means of three representative cases drawn from the three main Divisions of the faculty: the Sciences, Humanities, and Social Sci- ences. The stories of these three could be duplicated many times.

Though Dartmouth has always wel- comed research, within the last few years it has taken a strong stand and attempts to further it in every way possible. It has appointed a Committee on Research, now in its third year, which meets regularly and discusses the problems facing mem- bers of the faculty who are trying to pro- duce and get published. They are them- selves producing scholars sympathetic to all others interested in pushing back the boundaries of knowledge through inde- pendent investigations.

Professor Francis E. Merrill '26 (Soci- ology) is Chairman, and the other mem- bers are Nathaniel L. Goodrich (Librar- ian), Professors Clyde E. Dankert (Eco- nomics), Richard E. Stoiber (Geology), Leon Verriest (French), Wing Tsit Chan (Chinese Culture), Laurence N. Hadley Jr. (Physics).

Though research varies considerably from man to man and from field to field, though techniques vary, and though re- sults come neither quickly nor easily, Dartmouth professors are enabled as few persons are to combine their vocations and their avocations. Too often at other institutions a teacher is divorced from his research. His vocation is research, and his teaching, hardly better than a necessary avocation, interferes with his life work. Students suffer.

As one asks questions about Dartmouth classrooms and laboratories and studies at Dartmouth, one is struck again and again by the wisdom of Dartmouth's curriculum which places a premium upon a teacher being first of all a teacher with sufficient desire for research and experience to unite his avocation, with his main effort, instruction of undergraduates.

CONSIDER, for example, the activities of Roy P. Forster, aged 38, the young- est professor in the Department of Zool- ogy, who has what may seem to a nostal- gic alumnus an easy schedule of only 12 hours a week of teaching and a bit of re- search on the side.

He teaches a course called General Physiology, which is on a lecture-labora- tory basis and deals with chemical and physical explanations of fundamental life processes. Professor Forster puts his em- phasis in the laboratory upon quantita- tive experimentation on cold-blooded animals. His first job is to train students in basic physiological techniques and then to encourage them to do original re- search on a problem of their own choice. It might concern the nature of proto- plasm, cell permeability, animal move- ment, the nature of nervous and mus- cular action, environmental effects on the organism, the action of enzymes or vita- mins and hormones; growth and age, bio- electric potentials, biological oxidations, and reproduction.

A second course for Professor Forster in which he takes about a fourth of the lectures and laboratory periods is an ex- periment in general education with ob- jectives as outlined by President Conant of Harvard. Students in biology who are non-scientists examine a number of basic concepts in zoology and try to understand their historical developments and effects upon other fields of interest. They ex- plore for themselves the literature of zo- ology and the nature of zoological in- vestigation.

A third course for Professor Forster is research in General Physiology available only for properly qualified students.

Is that all there is to college teaching? An instructor is now free to play golf and ski, read novels and go to the movies? The answer is no.

ALSO MEETS STUDENTS INFORMALLY The classroom is not the only place where Professor Forster meets the stu- dents. He has in fact 228 of them, and according to the assumption underlying all pedagogy at Dartmouth, he is first and foremost teaching young men and only second is he teaching zoology. All 228 have standing invitations to drop into the laboratory for coffee, which is forever perking on a gas jet and is strong enough in looks and effects to jolt the most bo- vine into nervous agitation.

Nor is coffee the only thing imbibed; students, many of them headed for medi- cal school and in need of direction, drink up advice about the choice of profes- sional schools, request letters of recom- mendation, sound out the older man as to what they should do if they fail to get ac- cepted for post-graduate work.

Nor are uncertain and uneasy students the only ones who drink up advice. The best research men if they are going to get results must feel free to drop into Pro- fessor Forster's office, which is just off the laboratory, at any hour of the day. It is hard to estimate how much time goes into conferences, and the hours of informal teaching over a coffee cup may add up to another 12 or even double that num- ber in the course of a week.

So much (though the story is not com- plete) for Roy P. Forster, professor. But he is not only a professor; he is also a man. A hasty glance at his wrist watch and a last gulp of his cup of coffee and he is off to what kills off so many hours, a committee meeting. How much time for this meeting? It may be only an hour or two, but there are so many different kinds, and they come so frequently.

Professor Forster may be somewhat busier than the majority in his non-teach- ing college obligations, but he is by no means THE committee man. He is known rather as a teacher or as a research scien- tist. The committees he has served on within the past year are: Faculty Coun- cil, Faculty Lecture Committee for out- side speakers, Chairman of the Science Division, Faculty Adviser on Winter Sports for the Dartmouth Outing Club, Faculty Adviser for the Student Under- graduate Student Club, Special Commit- tee on Senior Fellowships, Interdivisional Committee for the Sciences, Executive Committee for the New Hampshire Acad- emy of Sciences.

Such a man, learned in his own par- ticular field and active in so many others, is often called on to talk before special groups, some of whom are seeking only entertainment with a little learned sea- soning and others whom are truly seek- ing knowledge. So Professor Forster is asked to speak and he accepts invitations before the Scientific Association, student clubs, and perhaps six or eight fraterni- ties during the year.

They are not too difficult to turn off, but what really puts the heat on him is when President Dickey asks him to give a Great Issue lecture to the entire senior class and to answer questions from these 600 students during another hour. It is stimulating and frightening and exacting, and the number of hours Professor For- ster puts in preparing is his own secret which no other faculty member would think of asking him about.

Though Professor Forster likes to think of himself as primarily a teacher, his asso- ciates outside Hanover might be disap- pointed in his reluctance to be known first, last, and always as- a research scien- tist. His lecture and laboratory assign- ment of is hours has already risen to about 40 to 45 hours, and now he is rela- tively free for his own investigations.

Professor Forster is known in the United States, Canada, and Europe for his investigations about animal kidneys, the general and comparative aspects of kidney functions rather than the strictly medical. His ultimate goal is to demon- strate how the cells which comprise the kidney work in chemical and physical terms. The problem is actually a general one, and Professor Forster has chosen the kidney rather than some other organ simply because it provides a good op- portunity to study what cells in general do. His ultimate goal in experiments is to try to get at the sources of living energy.

If such an ambition sounds almost vi- sionary, it must be said at once that he keeps his gaze on the microscope and the slide from the beginning and only occa- sionally allows his eyes to wander to the distant horizons of ultimate achievement. To be specific, he is at present treating fragments of living kidney tissue as though it were clinical substance and testing its activity in solution whose pre- cise chemical composition is known. After he has made cultures of the tissue, he then revives them and makes them carry on their functions which now can be pre- cisely measured under glass.

Here is where Professor Forster differs from his colleagues in the Social Sciences and the Humanities; he must work with other scientists in cooperative ventures, for the field is so complicated and time- consuming. He could not go far if he stayed only in his laboratory in the Na- tional Science Building in Hanover. He is forever on the prowl.

SUMMER RESEARCH IN MAINE He spends his summer at the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory in Salisbury Cove, Maine, to which flocks a summer colony of physiologists and bio- chemists from many colleges and univer- sities. There Professor Forster is a sort of liaison officer who arranges for the ex- change of ideas, the comparison of tech- niques, and intensified experimentation without interruptions from undergradu- ates. In this fashion he has spent his summers except for one year since 1937.

Members of the Dartmouth faculty get a semester off with full pay every seventh year for further study and research. Pro- fessor Forster was awarded last year on his a Guggenheim Fellowship and em- barked for England where he worked in laboratories at the University of Cam- bridge and visited laboratories and uni- versities in Europe. For some three months he carried on his investigations at the Bermuda Biological Laboratory for Research and got'in also a few licks back at Mount Desert Island.

Such activities enable him to publish learned articles, which have such melo- dramatic titles as: "An Examination of Some Factors which Alter Glomerular Ac- tivity in the Rabbit Kidney" or, even more lurid, this one: "Effect of Experi- mental Neurogenic Hypertension on Re- nal Blood Flow and Glomerular Filtra- tion Rate in Intact Denervated Kidneys of Unanesthetized Rabbits with Adrenal Glands Demedullated."

But Professor Forster's "twelve-hour week" is not over yet. He has still other obligations and investigations in renal physiology. As Section Editor of Biolog-ical Abstracts for which American, Eng- lish, Danish, Swedish, Belgian and Bra- zilian scientists contribute articles, Pro- fessor Forster translates, abstracts, and edits each month manuscripts dealing with investigations in the field of kidney studies.

By this time Professor Forster has en- croached somewhat on his eight hours al- lotted ordinarily to sleep and he has post- poned exercise in the open air out of— well—call it sheer laziness He is not yet through, and there are still the Christmas and Spring vacations. He devotes them to meetings in various American cities of learned societies to enable him to keep abreast of the field and also to keep others abreast of his own investigations. The most important of these societies are the American Society of Zoologists and the American Physiological Society.

A x 1 2-HOUR WEEK Only a few persons in the inner sanc- tums of the Administration Building know what Professor Forster's salary is for his 112-hour week. It is an open se- cret that Dartmouth with its relatively small endowment could hardly hope to compete against the big universities and research foundations, who would like to get a man of Professor Forster's caliber and have tried to. Why does he stay at Dartmouth for a half or even a third of the money he could easily get elsewhere? Why does he work so hard when else- where he could write his own research ticket and get rid of all the paper and committee work he does at Dartmouth as necessary and energy-consuming and possibly time-wasting routine?

"Why do I stay at Dartmouth?" asks Professor Forster and searches for a re- ply. "Many of my scientific friends can- not understand why, and to them I try to make no explanation. They wonder why I do not want to set my own pace. They keep asking me why I do not ac- cept a position at a university or a foun- dation where I would have trained as- sistants and would be freed from all duties except the solution of my immedi- ate problem."

He hesitated. "The Dartmouth alumni perhaps know why. I believe in the sound- ness of the students here. The bright seniors headed for medical school really offer more stimulus than a trained as- sistant who has become conventional in his scientific thinking.

"The Dartmouth administration per- haps know why. It is wonderful to work here. I am trusted. I can work on prob- lems that may take years to solve, prob- lems that may never be solved. The best research comes from the most complete freedom. Here no person and no organ- ization is peering over my shoulder and asking me what I have there and when it is going to be finished and how soon it is going to be published and how much prestige there is in it and whether the idea is saleable to a large pharmaceutical firm."

He hesitated again. "I know that I know why. It just so happens I enjoy the pressure of teaching and working closely with students. My research, my writing and editing help to keep me on my toes as a teacher. I don't know how I should otherwise make the transition from text- book physiology to original work for ad- vanced students. I'm content to go on teaching and combining it with research. After all, why not? I have an easy sched- ule: only 12 hours a week."

NOR CAN VERNON HALL JR., Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature, be considered to be "only a teacher," busy though he is on the lecture plat- form. He offers more than the usual num- ber of courses: Types of French Thought; History of Literary Criticism; Masters of the Modern Novel, which includes Dos- toevsky, Proust, Joyce, Kafka, and Thomas Mann; and the Romantic Move- ment in England, France, and Germany.

They are his chief concern, and he spends the major portion of his time and strength preparing and giving his lec- tures, conducting recitations, reading books and articles connected with these courses, correcting papers, and giving conferences to students.

Still a young man, aged 35, Professor Hall has found enough additional time, however, to publish some twenty schol- arly articles and book reviews in such journals as the Publications of the Mod-ern Language Society of America, ModernLanguage Notes, Modern Language Quar-terly, Proceedings of the American Phil-ological Society, Explicator, ComparativeLiterature, and Books Abroad.

Some of this time goes into editing pe- riodicals. He is Assistant Editor of Ren-aissance News and Consulting Editor of the Comparative Literature Section of Explicator.

Books for any professor are usually more important than articles; and Mr. Hall has published a full-length one; Renaissance Literary Criticism: A Studyof Its Social Content, under the auspices of the Columbia University Press, 1945. And he is working actively on three more: a history of literary criticism; a collec- tion of New England Sayings in collab- oration with Joel W. Egerer, Assistant Professor of English at New York Uni- versity; and a biography of Julius Caesar Scaliger, an Italian scholar and physician who lived nearly 400 years ago and is well known to the academic world and hardly known at all to the general pub- lic.

After five years of intensive work on Scaliger, Professor Hall went to France and Holland last summer to work in li- braries, complete the research he had done in Philadelphia and Hanover, and get his manuscript into final form for a pub- lisher.

Though Professor Forster in a labora- tory in Silsby Hall and Professor Hall in an office in Baker Library work just across North Main Street from each othen though they both produce articles and books, and though they are both known in the United States and Europe for their research, their methods and attitudes towards their materials and colleagues are not entirely alike. One is a scientist; the other, a humanist.

A research man in science like Roy Forster, who is also a highly skilled labora- tory technician, works in close coopera- tion with his fellow-scientists; a research man like Vernon Hall, who is associated with thousands of persons who lived long ago, works only in distant cooperation, if at all, with his fellow-humanists. The fields of humanistic studies available for research are far more limited than those in science. A research scientist works al- ways in the present and future, and the possibilities of choice and horizons are unlimited; a research humanist works m the past which has been gone over with fine tooth combs by thousands of patient and persistent investigators in a score of countries.

Science is progressive. Each scientist builds upon his predecessors' work. Much of the research of a few years ago may al- ready be outmoded. Thus a young scien- tist's main interest is knowing what his fellow scientists are doing now.

BOOKS ARE THE BIG CONCERN A humanist cannot so easily delimit his work. Nothing which has interested man or touched upon the lives of human be- ings can be considered outmoded. Thus his main concern is with books. He must be interested in what his fellows are do- ing today, but he must be equally inter- ested in everything which has been done in the past.

Professor Hall has found a topic foi a full-length scholarly biography based on original research which will interest not only the scholarly world because of new information and new ideas about the Renaissance but may also help introduce to the general public a most original and stimulating personality.

Everyone who knows anything about Professor Hall's investigations consider him to be exceptionally ingenious and as- tute, for he has unearthed not merely a manuscript or two unknown to research scholars but several hundred. They were reposing untouched and undusted, wait- ing for the Hall hand, in seven boxes and a large bundle of parchments, all about the Scaliger family and their doings from the 15th to the 19th century.

In any circumstances such an extensive manuscript collection of a prominent family is rare, and when one considers that the family is European and that the documents cover 400 years, the existence of such a collection in the United States is front-page news in any scholarly journal. And it is front-page news for alumni in- terested in a dynamic faculty to know that Professor Hall is the only one who has ever worked with these documents.

How in the world did the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia manage to acquire such a collection? As uncovered by Professor Hall in his inves- tigations, the story is romantic. It con- cerns a family with a passion for nobility so great that it made claims of descent from princes. It concerns family papers which had to be kept intact to prove doubtful points about ancestry. It con- cerns a maiden lady, the last of her line who ran up against a mesalliance which produced offspring more or less illegiti- mate with debased blood to supplant hers. And finally it concerns the loss of a French fortune in San Domingo and the decline of an illustrious French family un- til there was left in Philadelphia only one member who willed her papers to the American Philosophical Society which promised not to open the box they were in until she had died.

That is the story which Professor Hall unearthed. But as a research scholar, he was satisfied with it only as a beginning.

"The detective work in discovering whether the papers were hidden was de- ceptively easy," says Professor Hall with what seems like deceptive modesty. "I heard—never mind how—that some Scali- ger manuscripts were in existence in this country. That was very exciting news for me. I began at once checking libraries and asking questions of persons all over the country who might know. Finally I nar- rowed the field to one city, Philadelphia. It was then easy to discover that they lay in the archives of the American Philo- sophical Library."

With the papers before him, Professor Hall could decide what use he wished to make of them. Because the Scaligers for a long time, more than 400 years, were an important and influential French family, he had a number of possibilities in em- phasis in planning a book.

He decided to concentrate on Julius Caesar Scaliger because he was so brilliant and important a figure in the Renaissance and because he led a life as varied as it was exciting and because, surprising though it seems, no one has yet written a full-scale biography about him.

And so in a Baker Library office Profes- sor Hall nearly disappears from view be- hind pyramids of books, hundreds of them; manuscripts, thousands of them; cards by the gross and card indexes; letter files; and notes on all sizes and shapes of paper.

LANGUAGE DEMANDS ARE MULTIPLE But more than manuscripts, even if they have been untouched, are needed for a scholar to produce such a book. He must have a humanistic background. Spe- cifically, for the Scaliger papers he must have the ability to read French, Italian, and both Mediaeval and Renaissance Latin. He must be thoroughly read in Greek, Roman, French, Italian, and Eng- lish literatures. He must have more than a superficial knowledge of Renaissance sci- ence and of the philosophy of the Ancient World, the Middle Ages, and the Renais- sance.

The reason is that Professor Hall in- tends to relate Julius Caesar Scaliger to the 15th and 16th century European back- ground and to estimate his value as scien- tist, philologist, and critic. His contempo- raries were persuaded that he was the most learned man who had ever lived and greater than the greatest Greeks, Romans, and Renaissance scientists, critics, and philologists. Could such an estimate be judicious?

That estimate is exaggerated, but, in Professor Hall's opinion, he still stands out as a brilliant figure in the most bril- liant of ages. So keen and universal is Scaliger's literary criticism that two of our best critics, Sainsbury and Spingarn, praise him for his profundity and com- pleteness. So acute and thorough were his studies in Latin grammar that his book has been called "the first known scientific Latin grammar" by two leading modern philologists.

Scaliger's work as a doctor and scientist is just as significant, Professor Hall be- lieves. All histories of medicine make much of the fact that he ranked among the early experimenters who broke away from the conservative teachings of his time and that as a scientist he was the first to see that botany was a science which ought to exist by itself. Before him it had been studied only in terms of the value of herbs in medicine and agriculture.

Perhaps most significant of all is Scali- ger's work in philosophy. For 300 years Scaliger was an authority on Aristotle, whom he used as a means of presenting general and enduring views about the na- ture of man and the insoluble problems which man faces about conduct as soon as he begins to reflect.

One of Vernon Hall's major duties in writing his book is to reconsider the posi- tion of Scaliger in relation to other great Renaissance figures like Erasmus, the leader in the Revival of Learning in Northern Europe; Rabelais, the French monk known as a humorist and satirist and the creator of the racy and grotesque Pantagruel and Gargantua; Ronsard, the father of lyric poetry in France; and Nos- tradamus, the French physician and as- trologer.

The richness of the materials is enough to dazzle plodding research scholars whose eyes weaken with incessant and too often futile search in old books, periodicals, and manuscripts which too frequently yield unrelated and useless information on a topic which may interest only a handful of specialists. Professor Hall is ambitious. Nothing less than a treatment of Scaliger's life and all his works will satisfy him, and the works he will relate to his career, with an assessment of their importance.

It will be criticism with a difference, for Scaliger's age was rough and the language was tough and consequently lively. Scali- ger put the same fire and oratory, the same passion and anger into his criticism that politicians today put into their cam- paigns. r-r-it T 1 _P O 1 'XT nPT-

Though because of Scaliger's fiery per- sonality, Professor Hall's biography will seem to some romantic, he is documenting every fact; and he will thus avoid that de- based form of writing, the modern fic- tional biography written with an ounce of truth and a ton of bombast.

So the volume finally emerges not merely as a biography but also as a pic- ture of life, as it was lived up to the hilt, and of the learning and aspirations of the 15th and 16th centuries in France and Italy.

This is the vast scholarly enterprise that fills Professor Hall's "spare" time, and yet the teaching of Dartmouth under- graduates continues to be his primary em- phasis.

IF a scientist peers 10,000 times through a microscope and mounts 1,000 slides, if a humanist burrows through 1,000 miles of library shelves and studies 500 books and manuscripts in relative isolation, a so- cial scientist examines 1,000 public docu- ments and magazine articles and commu- nicates with a half dozen experts in his field to prepare himself for publication.

Social sciences are in perpetual flux, which will hardly submit to convenient static tests in laboratories. Unless a hu- manist is a mere popularizer or a facile producer of articles more journalistic than scholarly, a social scientist has a far richer field in economics, sociology, psychology, and government. He is under greater pres- sure also in fields so fluctuating. His judg- ments cannot be so absolute as a scientist's or a humanist's. He must be more flexibly pragmatic. New values are created almost overnight, and yesterday's headlines in foreign policy may be misleading if not downright false in the light of new knowl- edge today.

A social science professor is less able than most academicians to become only a specialist. Consider the activities, for ex- ample, of Professor John W. Masland of the Department of Government, known in Hanover, Washington, and Tokyo as an expert on Japanese-American political relations. He must occupy himself with such wide areas of activity and thought that an alumnus might think of him as the victim of an academic treadmill. The mere chore or reading government docu- ments is almost an eight-hour day in it- self, a minimum requirement. How else can he consider himself competent in a changing world?

Of necessity it follows that a social sci- entist must cooperate with others, and in this respect he resembles a scientist. Pro- fessor Masland in Washington and Tokyo was a member of a team. In Hanover he has a team also, the students in his course. In his Seminar on Major Problems of American Foreign Policy, for example, he gives no written examinations in the course but grades his student on their par- ticipation in group discussion and on oral and written reports and statements. This course, required of all majors in Interna- tional Relations, is devoted to a study of major contemporary problems of Ameri- can foreign policy.

The task is so complicated that one may well ask what are Professor Masland's em- phases. "I have two principal purposes," he explains. "First, I hope to provide a re- view of contemporary American policy and help each major solve to the best of his ability particular problems in the pres- ent-day scene. Second, I hope to repro- duce the essential features in the method by which responsible officials in Washing- ton deal with problems. I hope to show Dartmouth seniors how government policies are formulated and how decisions are made."

A leader in such a discussion group obviously has to have sharp differences of opinion among his students; indeed, they are proof that agreement, if finally reached, has been tested.

A professor, even if an expert with training not only in universities but also in the State Department and in the Army of Occupation in Japan, must have continual refreshment from outside sources and persons who have continual and intimate knowledge of what is going on in Washington.

Here is where Professor Masland's background serves him well. He can count on the International Studies Group of the Brookings Institution, headed by Dr. Leo Pasvolsky, former Special Assistant to the Secretary of State, and their annual study guide as a basic text for the course. Professor Masland, who has served on the Brookings staff, knows what he is about when he attempts to follow the general pattern and procedures developed by Brookings and used in seminars such as that held at Dartmouth in 1947 and attended by government officials, businessmen, newspapermen and teachers of international relations.

In such a course as this dealing with the conduct of American officials in foreign relations, the policies which they create, the continuous process of making current decisions within a framework of longrange objects and also within a framework of prevailing or expected circumstances at home and abroad, the students can needle Professor Masland into dynamic activity which he would scarcely feel if he cooped himself up too much in a library devoid of human contact.

"Why are our objectives in foreign policies taking this turn?" A big and simple question like this has to be answered. And other queries come in, some of them like those of children which so upset parents, except that they reach so far and go so deep: Great Power relations, British and Soviet positions and policies; European, Mediterranean, and Far Eastern Developments; and International Economic Relations; the American Constitution; the President; parties and public opinion and pressure groups; and military assistance to Western Europe.

The dynamic activity sometimes goes beyond the seminar room; it furnishes the stuff of an article which can be written with the proper investigation of source material and information from Washington. Seminar preparation or preparation for an article: both depend on intensive reading in newspapers, magazines, and books to a degree unusual even in a community where wide and varied reading is the rule.

Yet this seminar is only one course, and Professor Masland has three others. The first is an Introduction to Contemporary World Politics given with two others, Professors Pelenyi and Skilling, which emphasizes the responsibilities of the United States in world affairs.

The second, International Organizations, deals with institutions of international cooperation designed to handle problems of an economic, social, cultural, and humanitarian character, including the General Assembly of the United Nations, the Economic and Social Council, the Trusteeship Council, the International Bank, the International Labor Office, the International Civil Aviation Organization, and the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Students in this course have some knowledge of international law and the organization of security because they already have studied, under Professor H. Gordon Skilling, the Covenant of the League of Nations and the Charter of the United Nations, the pacific settlement of international disputes, the maintenance of security, and the reduction and limitation of armaments.

The third is called Contemporary Far Eastern Governments and Politics and concentrates upon the modern political systems of China and Japan with major emphasis on the rise and destruction of totalitarianism in Japan, revolution in China, and problems of political, economic, and social reconstruction in the Far East. The climax of this course is reached when Professor Masland attempts to make clear the complexity of the broader international problems with particular reference to the Cold War and to Soviet and American interests and policies.

His training brings the Orient to the threshold of the classroom. And his training made him a natural choice for President Dickey in one of the Great Issues lectures during its first year, for he more than anyone else then on the faculty or elsewhere could speak with authority on "National and International Approaches to Action."

That training began as far back as graduate school, 1935-1938, at Princeton when he produced a Ph.D. thesis entitled Group Interests in American Relationswith Japan. From 1938 when he began teaching at Stanford University as an instructor until this year he has been turning out a steady stream of articles about the Far Eastern areas.

His most important positions outside the academic world were Divisional Assistant in the Department of State, where he participated on a research team in producing papers on postwar Japanese problems, and Civilian Research Expert in the Government Section in Tokyo where he was attached to General Mac Arthur's staff at General Headquarters. The Government Section is responsible for forming occupation policies in political spheres. General Courtney Whitney was Professor Masland's chief. Out of this activity came further work in framing a new Japanese Constitution and the revision of many basic laws.

"I was only one of a research team," emphasizes Professor Masland. "All of us had a hand." It is also true that each member had a speciality; his was investigation and advice about local government.

After the team had done what it could, Japanese were called in to criticize, contribute more information, and help on revision.

Such work suggests the trends in social science research, or, at least, in research among scholars specializing in Government. War has changed its character. Small teams in the Department of State pool their knowledge, attempt to define objectives, accumulate new information, and draw up policies which may bring order out of the confusion of post-war chaos.

Professor Masland is only one of a number of scholars with a practical bent who can see more rapid improvements in political structure as a result of group effort. The papers of policy which he helped to draw up in Washington are now bearing fruit in the administration of the New Japan under General Mac Arthur.

At Stanford Professor Masland continued to function in new team work. With three or four others he cooperated in preparing material for teaching American army officers headed for Japan. The Masland research team took nine months to work up printed material for use in indoctrination, and they had the help of three or four officers fresh from Japan.

In Japan itself another team of research men makes studies with all material available in the hope of building a better government capable of bringing out the heretofore untapped energies of the Japanese for their own general welfare.

Eight years of teaching experience at Stanford and government training in Washington and Tokyo matured Professor Masland quickly and gave him so much competence and prestige that Dartmouth offered him in 1946, when he was only 34 years old, a full professorship and exceptional teaching opportunities.

Hanover has not confined him since then. The summer of 1948 found him Visiting Professor at Columbia University and Consultant for the Commission on the Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government in Washington. He was called to Washington again in February 1948 by the Brookings Institute to help make plans for a seminar to be held at Stanford University during the following June and July, which of course he attended.

The College chose him and Dean Stearns Morse in 1948 to address Dartmouth alumni in Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and Columbus, where he spoke about the American occupation of Japan.

At Stanford Professor Masland won considerable popularity as a speaker and was much in demand. In Hanover he has been forced to decline such engagements and cut down on his research activities owing to the long illness and death in June 1949 of his wife, Harriet Gilbert Masland, a Hanover girl whom he married in 1939. He has a daughter and a son, and the problem of bringing them up and carrying his academic load has not been an easy one to solve.

A mere listing of Professor Masland's magazine articles and their titles would indicate that his specialized experiences have really amounted to research in action and that his main problem is in finding time to get to his typewriter, not in finding something to write about. His essays have appeared in quick succession in The Annals, Public Opinion Quarterly,U. S. Naval Institute Proceedings, PacificHistorical Review, American Political Science Review, Public Administration Review; and his book reviews in Far EasternQuarterly, Pacific Northwest Quarterly,Pacific Historical Review, and the NewYork Times Book Review.

Professor Masland has an office in Thornton, a small one, which is in a cluster of other offices belonging to the staff of the Department of Government, but he has been doing his chief work apologetically and against his will in a hideaway, a cubicle on the tenth level of Baker Library. There it is almost impossible for anyone to reach him. He takes an elevator to the ninth level, climbs a flight of stairs to the tenth, unlocks a door, goes down a corridor to Room 1002, unlocks another door, and locks himself in with his desk, chair, bookcase, lamp, and typewriter.

"I regret cutting myself off from the students, but it is only temporary, and I had to get my book out," he says.

This book is a revision and enlargement of The Governments of ForeignPowers, first published by Holt in 1947. Philip W. Buck of Stanford University is co-author. It runs to about 800 pages and will appear early next year. Professor Masland's contribution devoted to China and Japan runs to some 250 pages of print. Unlike most authors with a manuscript in the hands of the publishers and only the tedious job of reading proof, he must watch despatches between now and the publication date, for the Chinese situation controlled by the great god Whirl is changing so rapidly that what he writes about the Communists today may be outdated by tomorrow.

"When this volume appears, I hope to find a new field of interest," Professor Masland says, aware that in Hanover he is too far removed from Japan to continue to be the expert he would like. He feels that he is perhaps through this phase of his intellectual life.

"I know what I want to do," he remarks as he collects his thoughts. "It will be something about the influence of air power upon the development of American foreign policy. But I am not sure just how to go about it. I am keen to get going again. I have not done any research for so long that I want to prove to myself that I still have a mind."

He will pursue his research or some of it in actual conversation in Washington with Government officials who can tell him what newspaper men do not know or do not dare to print. He will read as a matter of course a hundred different magazines and a thousand, articles.

When others are playing bridge in a care-free Hanover, hurrying on to the Nugget, or just chatting with friends in the Inn Coffee Shop, Professor Masland may be leaving his senior seminar with some new ideas from students who have needled him. He will hurry to his tenthlevel sanctuary from which will emerge the clicking of typewriter keys. Some day, somehow, from it may come a book about some as yet undetermined phase of the influence of air power on American foreign policy, depite the temptations of that all-pervading leisure which professors in Hanover with only a 12-hour week enjoy.

IT Is THE DREAM of nostalgic alumni to return to Hanover and let the hills shut off the racket and the roar of the modern business world. They would like to relax, stretch out their legs and read for the fun of it before a fireplace fire, and follow the Big Green teams. They would like to teach a course and play around in the Library with a little research.

It is a dream so fascinating that professors wish that they had time for it. They too would like to sprawl in an easy chair and do a little recreational reading before a blazing log. They cannot very often. If business has become complex and high pressured, so also has the academic world.

A Dartmouth classroom is not big enough any longer, if it ever was, to fulfill a competent professor who is also a research man in need of a laboratory or a library. Nor indeed is a Hanover laboratory or Baker Library big enough. In the search for knowledge and truth, a scientist is led to laboratories all over the world; a humanist, from Philadelphia to the Renaissance in France and from there to Ancient Greece; a social scientist, from Washington to California to Tokyo and back to work on a problem of such world-wide importance as the influence of air power on American foreign policy.

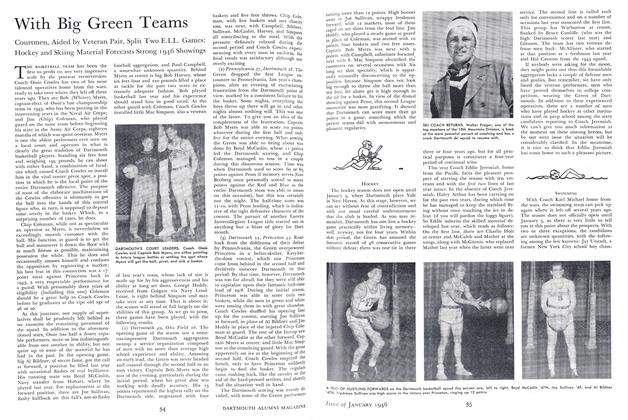

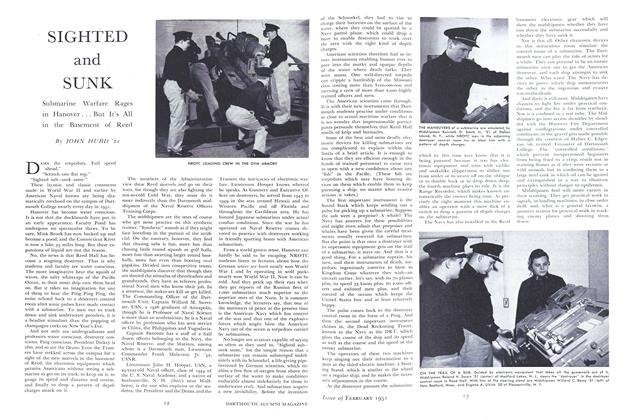

SCIENTIST AT WORK: Roy P. Forster, Professor of Zoology and Chairman of the Division of the Sciences, carrying out a research project in his Silsby Hall laboratory. He was a Guggenheim Fellow last year.

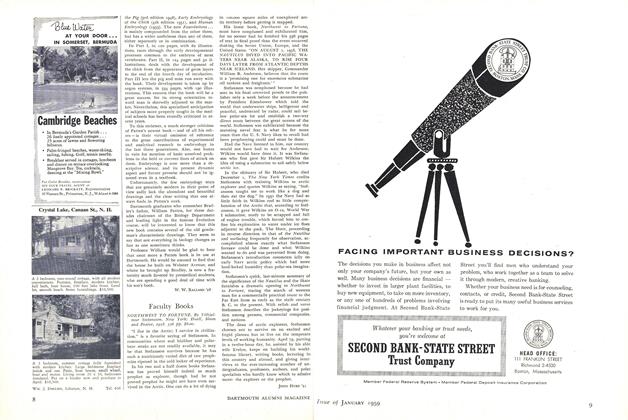

ONE OF THE BUSIEST SCHOLARS AT DARTMOUTH is Vernon Hall Jr., Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature, shown viewing microfilm as he digs into the Renaissance and the life of Julius Caesar Scaliger.

AN AUTHORITY ON JAPANESE-AMERICAN POLITICAL RELATIONS, John W. Masland, Professor of Government, must carry his researches into nearly all the social sciences. He hopes to turn next to air power.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

January 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

January 1950 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART, 3rd, JULIUS A. RIPPEL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1938

January 1950 By JOHN H. EMERSON, WILLIAM H. MCMURTRIE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

January 1950 By WILLIAM H. HAM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

January 1950 By GEORGE W. RAND, MAX A. NORTON, WINDSOR C. BATCHELDER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

January 1950 By DONALD G. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD, ROBERT P. BURROUGHS

JOHN HURD '21

-

Article

ArticleSIGHTED and SUNK

February 1951 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksNORTHWEST TO FORTUNE.

JANUARY 1959 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE PREVALENCE OF NONSENSE.

NOVEMBER 1967 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksOFF THE SAUCE.

NOVEMBER 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksSCENERY OF THE WHITE MOUNTAINS.

MARCH 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksBull Market

September 1975 By JOHN HURD '21