Submarine Warfare Rages in Hanover . . . But It's All in the Basement of Reed

DAMN the torpedoes. Full speed ahead." "Scratch one flat top." "Sighted sub—sank same."

These laconic and classic comments made in World War II and earlier by American Naval heroes are being dramatically reechoed on the campus of Dartmouth College nearly every day in 1951.

Hanover has become water conscious. It is not that .the duckboards have put in an early appearance. Faculty Pond has undergone no spectacular thaws. To be sure, Mink Brook has now backed up and become a pond, and the Connecticut River is now a lake 35 miles long. But these expansions of liquid are not the reason.

No, the news is that Reed Hall has become a seagoing destroyer. That is why students and faculty are water conscious. The more imaginative hear the squish of waves, the salty whitecaps of the Pacific Ocean, as their stout ship cuts them head on. But it takes no imagination for any of them to hear the Ping Ping Ping, the noise echoed back to a destroyer control room after sonic pulses have made contact with a submarine. To men out to track down and sink underwater prowlers, it is a headier stimulant than the popping of champagne corks on New Year's Eve.

And not only are undergraduates and professors water conscious, destroyer conscious, Ping conscious. President Dickey is also, and so are the Deans. Even the Trustees have trekked across the campus for a sight of the new marvels in the basement of Reed, the electronic equipment which permits Americans without seeing a submarine to get on its track, to keep on it, to gauge its speed and distance and course, and finally to drop a pattern of depth charges smack on it.

The members of the Administration view these Reed marvels and go on their ways, for though they are also fighting the not-so-cold Cold War, they must do it more indirectly than the Dartmouth midshipmen of the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps.

The midshipmen are the ones of course who get most practice on this synthetic trainer. "Synthetic" sounds as if they might face boredom in the pursuit of the artificial. On the contrary, however, they find that chasing subs is fun, more fun than chasing little round squash or golf balls, more fun than swatting larger round baseballs, more fun even than booting oval pigskins. Divided into competitive teams, the midshipmen discover that though they are denied the stimulus of cheerleaders and grandstands, they have as referees professional Naval men who know their job. In a sentence, the stakes are kill or get killed. The Commanding Officer of the Dartmouth Unit, Captain Willard M. Sweetser, USN, a 1926 graduate of Annapolis, though he is Professor of Naval Science is more than an academician; he is a Naval officer by profession who has seen service in China, the Philippines and Yugoslavia.

Captain Sweetser has a staff of a half dozen officers belonging to the Navy, the Naval Reserve, and the Marines, among whom is a Dartmouth man, Lieutenant Commander Frank Malavasic Tr. '42, USNR.

Lieutenant John H. Hooper, USN, a 29-year-old Naval officer, class of 1944 of the U. S. Naval Academy, and a native of Sanbornville, N. H. (that's near Wolfboro), is the one who explains to the students, the President and the Deans, and the Trustees the intricacies of electronic warfare. Lieutenant Hooper knows whereof he speaks. As Gunnery and Executive Officer on destroyers, he served from 1943 to 1949 in the seas around Hawaii and the Western Pacific and off Florida and throughout the Caribbean area. He has hunted Japanese submarines under actual combat conditions. Since the war he has operated on Naval Reserve cruises devoted to practice with destroyers working in friendly sparring bouts with American submarines.

From a world grown tense, Hanover can hardly be said to be escaping. NROTC students listen to lectures about how the German unter see boot nearly won World War I and by operating in wolf packs nearly won World War II. Now it can be told. And they prick up their ears when they get reports of the Russian fleet of 1.000 submarines much superior to the superior ones of the Nazis. It is common knowledge, the lecturers say, that one of the mainstays of peace at the present time is the American Navy which has control of the seas and that one of the explosive forces which might blow the American Navy out of the ocean is torpedoes carried by submarines.

No longer are aviators capable of saying so often as they used to, "Sighted subsank same," for the simple reason that a submarine can remain submerged indefinitely with its Schnorkel, a life-giving pipe, invented by German scientists, which enables a free flow of oxygen from above the surface of the water to make conditions endurable almost indefinitely for those in underwater craft. And submarines acquire a new invisibilitv. Before the invention of the Schnorkel, they had to rise to charge their batteries on the surface of the water, where they could be spotted by a Navy patrol plane, which could drop a buoy to enable destroyers to work over the area with the right kind of depth charges.

American scientists therefore had to invent instruments enabling human eyes to peer into the murky and opaque depths of the water where death lurks. They were musts. One well-directed torpedo can cripple a battleship of the Missouri class costing more than $100,000,000 and carrying a crew of more than 2,000 highly trained officers and men.

The American scientists came through. It is with their new instruments that Dartmouth students practise under conditions so close to actual maritime warfare that it is no wonder that impressionable participants persuade themselves that Reed Hall smells of kelp and barnacles.

Some of the best and most deadly electronic devices for killing submarines are too complicated to explain within the limits of a brief article. It is enough to know that they are efficient enough in the hands of trained personnel to cause eyes to open with a new confidence about any "fish" in the Pacific. (These fish are torpedoes which may have homing devices on- them which enable them to keep pursuing a ship, no matter what evasive actions it takes.)

The first important instrument is the Sound Stack which keeps sending out a pulse for picking up a submarine. Suppose the sub were a porpoise? A whale? The Navy has answers for these possibilities and might even admit that porpoises and whales have been given the careful treatments usually reserved for submarines. But the point is that once a destroyer with its supersonic equipment gets on the trail of a submarine, it stays on. And that is a good thing. For a submarine captain, his men, and their instruments of death, torpedoes, ingeniously contrive to blow to Kingdom Come whatever they wish—an aircraft carrier, let's say, with its 70 planes plus, its speed 33 knots plus, its 2,000 officers and enlisted men plus, and their control of the oceans which keeps the United States free and at least relatively happy.

The pulse comes back to the destroyer control room in the form of a Ping. And then the second important instrument chimes in, the Dead Reckoning Tracer, known to the Navy as the DRT. which plots the course of the ship and its speed as well as the course and the speed of the enemy submarine.

The operators of these two machines keep singing out their information to a man at the third electric machine, a Steering Stand, which is similar to the wheel on a regular ship, and he makes the necessary

adjustments in the course. As the destroyer pursues the submarine, which by this time may know that it is being pursued because it too has electronic equipment and tries with ratlike and snakelike slipperiness to slither out from under or to weave off on the oblique or to double back or to drop down deep, the fourth machine plays its role. It is the Range Recorder, which makes known automatically the correct firing time. At precisely the right moment this machine enables an operator with a mere flick of a switch to drop a pattern of depth charges on the submarine.

The Navy has also installed in the Reed basement electronic gear which will show the midshipmen whether they have run down the submarine successfully and whether they have sunk it.

Nor is this all. Other electronic devices in this miraculous room simulate the control room of a submarine. The Dartmouth men can play the role of actors for a while. They can pretend to be an enemy submarine crew out to get the American destroyer, and each ship attempts to sink the other. Who wins? The Navy has devices to prove which ship outmaneuvers the other in the ingenious and evasive war-to-the-death.

And there is still more. Midshipmen have chances to fight fire under practical conditions, and the fire is far from synthetic. Nor is it confined to a test tube. The Midshipmen go into action shoulder by shoulder with the Hanover Fire Department against conflagrations under controlled conditions in the gravel pits made possible through the courtesy of Halsey C. Edgerton '06, retired Treasurer of Dartmouth College. The "controlled conditions," which prevent inexperienced beginners from being fried to a crisp, result not in training flames as if they were recruits or wild animals but in confining them to a large steel tank in which oil can be ignited and extinguished in a way to illustrate principles without danger to epidermis. Midshipmen find still more variety in their training. They get practical work in signals, in loading machines, in close order drill, and, what is a general favorite, a gunnery trainer for practical work in tracking enemy planes and shooting them down.

So expert did Naval gunners become in the last war that in one battle they knocked so many Japanese planes out of the sky that this engagement has become known in history books as the "Marianas Turkey Shoot." (The score: 402 Japanese planes. Americans 17.)

These sorts of training are not confined to the Navy students at Dartmouth. Even grayhaired professors engage, evenings, in mock warfare. (The majority of them as a matter of lact are in the full flush of brown or black or red-haired early middleage.) They belong to Volunteer Composite Unit 1-37, composed of officers and enlisted men of the Naval, Coast Guard, and Marine Corps Reserve from Hanover, Lebanon, White River Junction, and Woodstock, which is under the leadership of A. Murray Austin '15 of Norwich, a retired banker, who in this work has been able to utilize his wide experience in the Naval Reserve in World War I and in World War II, which was climaxed by his assignment as Commanding Officer of the USS LENAWEE, an attack transport, opera ling with the Third Amphibious Forces of the U. S. Pacific Fleet. In the face of considerable lethargy on the part of former service men in this area, Commander Austin succeeded during the course of several weeks in building up an enlivening Volunteer Composite Unit 1-27, and its membership is now 32 officers and 28 enlisted men, who meet weekly for drills which include various kinds of training aids, moving pictures of specialized warfare, blinker practice, and instruction in navigation and plotting. They have listened to lectures given by experts in the last war among whom are Commander John H. Turner on "The Modern Submarine and Its Mission"; Francis L. Higginson on "Anti-Submarine Warfare"; Captain Thomas Parran Jr. USMC on "Amphibious Operations in Normandy and Okinawa"; Prof. Richard H. Goddard '20, Director of die Shattuck Observatory, on "The Weather and Tactical Planning"; David C. Nutt '41 on "Navy Operations in the Arctic and Its Problems"; Prof. Donald Bartlett '24 on "Naval Intelligence"; Dr. Ralph W. Hunter '31 on "The Effects of Radiation and Atomic Explosions on Human Health"; A. Murray Austin on "Amphibious Operations"; Prof. Albert L. Demaree on "A Survey of Naval History"; and Admiral H. K. Hewitt, USN, Rtd., on "The North Africa and Italy Invasions," of which he personally was in charge.

Since Volunteer Composite Unit 1-27 began to function, more than 50% of its enlisted personnel have been called back to active duty, shipped out, and are now fighting North Koreans and Chinese Communists overseas. This fact indicates that the Unit has a practical value in training men for combat.

Naval Reserve officers with Dartmouth connections who are members of Volunteer Composite Unit 1-27 include:

Lieutenant (j.g.) Charles M. Ashton Jr. '46, son of Charles M. Ashton '20 of Rogers, Arkansas, who went through Aviation Pre-Flight and Operations Training in Athens, Great Lakes, and Atlanta and served as Assistant Operations Officer at Okinawa and in Japan;

Lieutenant Forrest P. Branch '33, Social Science and History teacher and football coach at the Hanover High School, who served in Communications at Leyte and Luzon and other places in the Philippines on Admiral Kinkaid's Staff;

Lieutenant Edward M. Cavaney, son-inlaw and business partner of Archie B. Gile '17, who trained in Hanover and Princeton, was First Lieutenant afloat, and served as Flag Secretary in the China Service with Squadron 8;

Lieutenant Edward T. Chamberlain Jr. '36, Executive Officer of the College, who served for three and a half years of training and service with small escort vessels of the Navy in the Caribbean and Pacific—his most important assignment was skipper of a control vessel at the invasion of Tinian when firing got really hot.

Lieutenant Commander Arthur O. Davidson, Assistant Professor of Education, who was concerned with the training of officers and men for destroyers and cruisers operating in the Pacific;

Commander Albert L. Demaree, Professor of History, who had sea duty in World War I and in World War II had charge of the writing of Naval Orientation, used by NROTC students in 52 colleges and by all Naval Reserve officers in Naval Correspondence Courses as a requirement for promotion,

Lieutenant (j.g.) Allen E. Howland '44, Executive Secretary of the Hitchcock Clinic, who had sea duty at Kwajalein Atoll, New Guinea, the Philippines, and Borneo;

Lieutenant Commander John Hurd '21, Professor of English, who was a ground school officer in Naval Aviation and taught the recognition of planes and ships to British and American aviation cadets at Naval air stations in this country;

Lieutenant Commander Mason I. Ingram '29, Assistant Comptroller of Dartmouth College, who spent five and a half years both in Army and Navy with duties in disbursing, accounting, and commissary and supply work at Fort Bragg, Davisville, R.I., and Quoddy, Me.;

Lieutenant Richard B. McCornack '41, Instructor in History, who spent two years as Commissary Officer at the U. S. Naval Air Station in Coco Solo, Canal Zone;

Lieutenant Commander Elliott B. Noyes, '32, coach of track and cross-country at Dartmouth, who was assigned for three and a half years to the U. S. Navy Pre-Flight School in lowa City, where he was Regimental Commander;

Commander David C. Nutt '41, Arctic Specialist attached to the Dartmouth Museum, who made a half dozen exploratory trips from 1935 on with the R. A. Bartlett Greenland Expeditions, served as Naval observer and Representative of the Smithsonian Institute on its Antarctic Development Project, and in 1949 was Commander of the Labrador Expedition and Master of the Schooner Blue Dolphin.

The membership of Volunteer Composite Unit 1-27 includes also a number of Dartmouth undergraduates, some already commissioned with a war record back of them, some of them freshly enrolled Seamen and Seaman Recruits: James D. Binder '52, Seaman Recruit of Leonia, N. J.; Robert L. Callender '53, Seaman Recruit, of Narberth, Pa.; Philip N. Kniskern, Tuck School, Ensign, of Swarthmore, Pa.; Paul S. Miller, Tuck School, Ensign, of Pleasantville, N. J., Lawrence F. Moran, Tuck School, Ensign, of Swampscott, Mass.; Charles J. Urstadt '49, Ensign, of Pelham Manor, N. Y.; Stephen J. Wolff Jr. '51, Seaman Recruit, of St. Louis, Mo.

A Dartmouth professor once lecturing to an enthralled class on the symmetry and resultant felicity of the medieval pattern of life remarked, "The fenestration of Reed Hall is one of the most satisfying because one of the most beautiful sights on the campus."

The remark made sense, and the windows of Reed are still beautiful. The world being what it is today, Dartmouth College students tend to focus their gaze not on them but on the Pacific 3,000 miles beyond the elm trees fringing the campus. But their call has not yet come for that body of water, and so they flock into the windowless depths of Reed to glue their eyes on electronic equipment making pinging noises.

Alumni who fear that Dartmouth College students and professors are cutting themselves off from the outside world of conflict may take some comfort in knowing that if Reed Hall still has superb portholes on its upper decks, belowdecks it has the most modern electronic equipment for destroyer duty.

It is to be expected in these days that college athletes turning their thoughts away from athletic fields to destroyer-submarine war in the Reed basement may say, "Boy, I sank three of those Russian s. o. b. subs." But it is news indeed when a gray-haired member of the Naval Reserve, a professor, after a particularly harrowing night at sea on board the USSReed, remarks jubilantly to his wife, "Pinged sub. Blasted same."

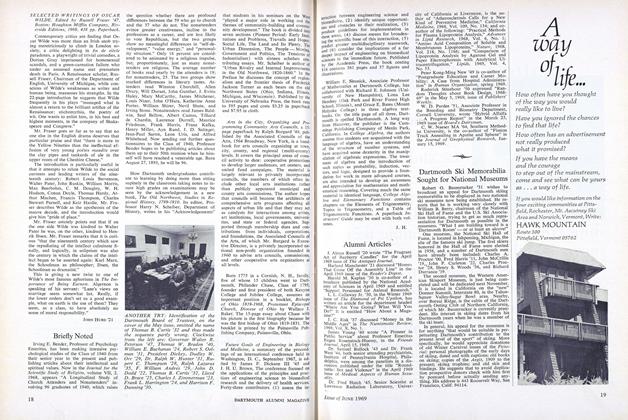

NROTC LOADING CREW IN THE GYM ARMORY

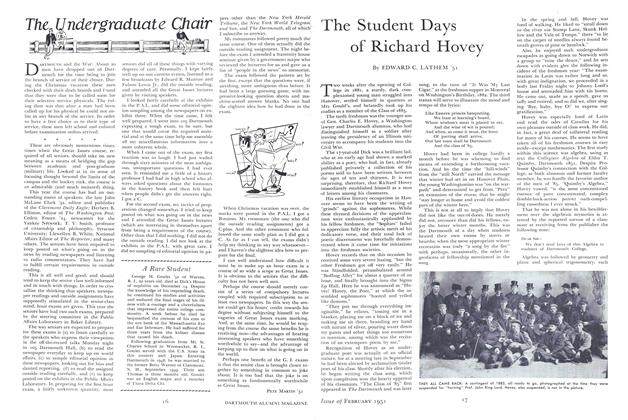

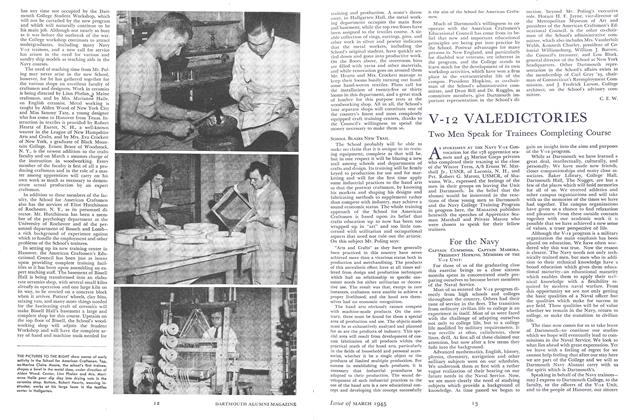

THE MANEUVERS of a submarine are simulated by Midshipman Kenneth D. Smith Jr. '51 of Staten Island, N. Y., while NROTC men in the adjoining destroyer control room try to blast him with a pattern of depth charges.

ON THE TRAIL OF A SUB: Guided by electronic equipment that takes all the guesswork out of it, Midshipman Roland H. Swain '51 (center) of Medford Lakes, N. J., steers the "destroyer" in the destroyer control room in Reed Hall. With him at the steering stand are Midshipmen Willard C. Rowe '51 (left) of New Bedford, Mass., and Eugene A. Ulrich '50 of Pleasantville, N. Y.

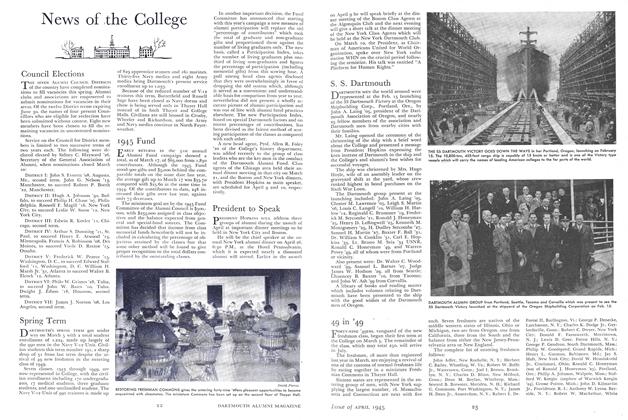

PROJECTION EQUIPMENT, also of the latest model, is used in Reed Hall's sub-surface laboratory to show midshipmen how submarine and destroyer maneuver in their deadly battle at sea.

THE MECHANICS OF A TORPEDO are explained to Midshipmen Smith and Ulrich by Lieut. John H. Hooper, USN, Instructor in Naval Science, who was executive officer on a destroyer in the last war.

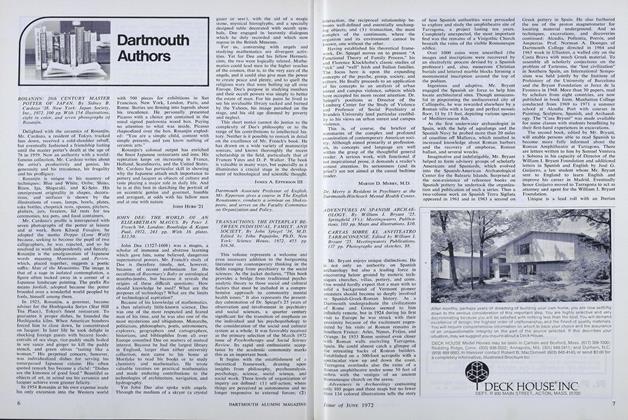

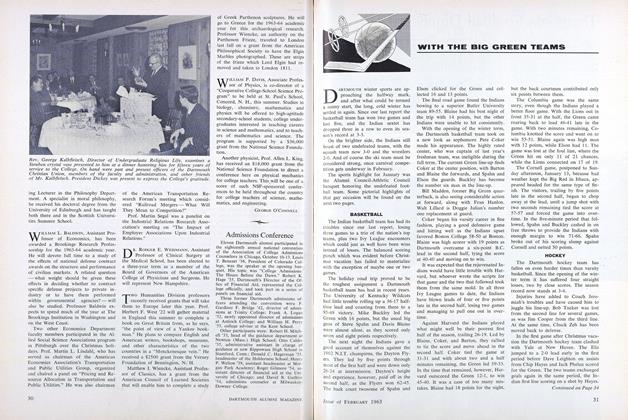

KEEPING ABREAST OF NAVAL DEVELOPMENTS, members of the Dartmouth faculty and administrative staff form a large part of Volunteer Composite Unit 1-27 which meets weekly under the leadership of Comdr. A. Murray Austin '15, USNR, shown addressing the group at Thayer School. Officers and enlisted men of the Reserve Corps of the Navy, Marines and Coast Guard make up the Unit personnel.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Student Days of Richard Hovey

February 1951 By EDWARD C. LATHEM '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

February 1951 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, JACK D. GUNTHER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

February 1951 By GEORGE F. THERIAULT, LEE W. ECKELS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

February 1951 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, GILBERT H. FALL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

February 1951 By SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III

JOHN HURD '21

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

November 1975 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN, THOMAS W. STALEY, JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureSoldiers As Policy Makers

February 1951 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksSELECTED WRITINGS OF OSCAR WILDE.

JUNE 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksCARTAS SOBRE EL ANFITEATRO TARRACONENSE.

JUNE 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

JANUARY 1973 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksOHIO AN ARCHITECTURAL PORTRAIT

October 1973 By JOHN HURD '21

Article

-

Article

ArticleFRATERNITY SITUATION

July 1920 -

Article

ArticleFirst-Hand Account of a Forest Fire

January 1948 -

Article

ArticleSCHOOL FOR CRAFTSMEN

March 1945 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleOur Own Class Notes

April 1945 By CORY FORD, MAJOR USAAC -

Article

ArticleBASKETBALL

FEBRUARY 1963 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

ArticleThe "Evil Empire" Strikes Back

April 1993 By Dean Engle '91