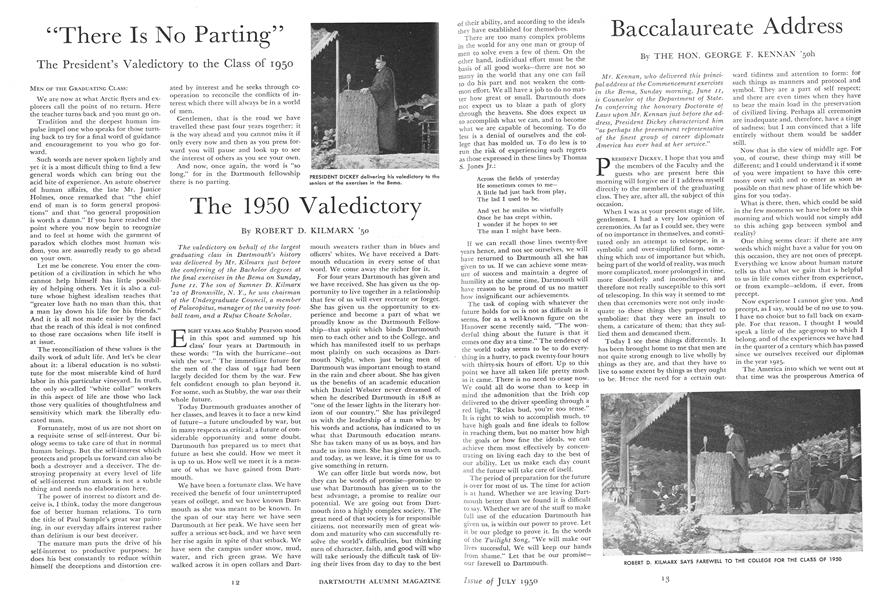

Mr. Kennan, who delivered this principal address at the Commencement exercisesin the Bema, Sunday morning, June n,is Counselor of the Department of State.In conferring the honorary Doctorate ofLaws upon Mr. Kennan just before the address, President Dickey characterized him"as perhaps the preeminent representativeof the finest group of career diplomatsAmerica has ever had at her service.

PRESIDENT DICKEY, I hope that you and the members of the Faculty and the guests who are present here this morning will forgive me if I address myself directly to the members of the graduating class. They are, after all, the subject of this occasion.

When I was at your present stage of life, gentlemen, I had a very low opinion of ceremonies. As far as I could see, they were of no importance in themselves, and constituted only an attempt to telescope, in a symbolic and over-simplified form, something which was of importance but which, being part of the world of reality, was much more complicated, more prolonged in time, more disorderly and inconclusive, and therefore not really susceptible to this sort of telescoping. In this way it seemed to me then that ceremonies were not only inadequate to these things they purported to symbolize: that they were an insult to them, a caricature of them; that they sullied them and demeaned them.

Today I see these things differently. It has been brought home to me that men are not quite strong enough to live wholly by things as they are, and that they have to live to some extent by things as they ought to be. Hence the need for a certain outward tidiness and attention to form: for such things as manners and protocol and symbol. They are a part of self respect; and there are even times when they have to bear the main load in the preservation of civilized living. Perhaps all ceremonies are inadequate and, therefore, have a tinge of sadness; but I am convinced that a life entirely without them would be sadder still.

Now that is the view of middle age. For you, of course, these things may still be different; and I could understand it if some of you were impatient to have this ceremony over with and to enter as soon as possible on that new phase of life which begins for you today.

What is there, then, which could be said in the few moments we have before us this morning and which would not simply add to this aching gap between symbol and reality?

One thing seems clear: if there are any words which might have a value for you on this occasion, they are not ones of precept. Everything we know about human nature tells us that what we gain that is helpful to us in life comes either from experience, or from example—seldom, if ever, from precept.

Now experience I cannot give you. And precept, as I say, would be of no use to you. I have no choice but to fall back on example. For that reason, I thought I would speak a little of the age-group to which I belong, and of the experiences we have had in the quarter of a century which has passed since we ourselves received our diplomas in the year 1925.

The America into which we went out at that time was the prosperous America of the twenties—the America of the economic boom and prohibition. Our society was then already abnormally competitive, by world standards—competitive in the social as well as in the business sense. There was a tendency, which has endured to this day, to carry this competition close to the economic margins and to the margins of strength and energy, leaving little slack for composure, for contemplation, for detachment.

Remember that at that time people's vision was still beclouded by the dizzy advance of economic life. Many things which today we know the true value of were then new to us and we were uncertain of their meaning. A knowledge of human history should have warned us, perhaps, against the assumption that material things and gadgets might have more than a limited bearing on human happiness. But the changes then occurring in American economic life were spectacular and unsettling. Our eyes were dazzled by all this brilliance. We had no way of knowing just what was behind it. People seriously believed that perhaps the ability to live life at a greater speed and to do things with less labor was alone going to work a revolution in the possibilities for human happiness and self-expression. People were impressed by the fact that all these changes were the result not of any deliberate program of organized society but of a headlong personal competition for money and success; and they had a natural tendency to view this competition as an absolute good, disregarding the context of time and circumstance in which it had to proceed.

In those days, therefore, participation in this competition was more than just a personal choice: it was a pervasive social compulsion. It was the only course which was widely and thoroughly approved by your elders. There were few alternatives to it. And even if you felt the stirrings of a desire to influence the affairs of society as a whole rather than just to improve your own personal position, the best route to this objective still lay through an initial participation in the race for economic and social advantage.

It is not surprising, in retrospect, that most of us ended up, within a few years of our departure from college, in the lower rungs of this immense competitive ladder, and that we began to feel at an early date the bite of its relentless disciplines and routines. In this world of personal competition: of family budgets, of children, of jobs and bosses and of keeping up with the Joneses, the brave resolves of earlier years found no dramatic disillusionment; they simply lost their freshness and their immediacy; they sank down, quietly, almost imperceptibly, through the sands of habit and custom, and we were only dimly and wearily aware of their disappearance. Gradually—so gradually that we seldom noticed it—the effort of daily life became an end in itself; the purposes underlying it became more remote and obscure. They were personal rewards, to be sure; but they were highly relative ones, and extraordinarily unexciting when one thought of them outside the personal context. The likelihood that life was going to be an adventure, that we were going to change the face of the world, was fading. The grand design was receding. The mystery and the color that had marked the early dawn were giving way to the flat, hard sunshine of mid-day.

On top of this came the depression. It was not without value. It sobered us. It caused us to become thoughtful about things we had taken for granted. It produced new insights into the relationships between governmental power and private enterprise. Some of us found, for a time, a sense of self-fulfillment through partcipation in new governmental and social undertakings. There were visions of a greater purposefulness in American society: of goals consciously selected rather than being permitted to flow from the anarchic processes of self-interest, and of a collective effort to proceed toward those goals in an organized way.

But along with all of this, the depression left many of us with a haunting sense of helplessness before the obvious complexities of our time: with a feeling that the fortunes of the individual lay no longer in his own hands but in the action of forces beyond his knowledge and his control, and a consequent pre-occupation with that fiction which we call security—that treacherous will-o'-the-wisp the pursuit of which always carries you, as in some exasperating nightmare, to exactly the opposite goal from the one that you wanted to reach. The anxieties of the depression caused us to forget that all life is inevitably crowned with death, and that the pursuit of total security can only ruin the bird in the hand, which is our best use of the time allotted to us on this earth, without bringing us the bird in the bush, which would be an immunity from the laws of change and renewal.

From all this we were relieved, temporarily, by the war. The war did not solve these problems for us, but it thrust them momentarily into the background. For some, of course, it brought heroism and death. Of these I am not speaking. They stand today above our judgment. For the majority of us it brought a relaxation of the excitement of participation in a broader undertaking. It called for effort and sacrifice: for the sublimation of individual life into a common cause. In many ways, these things were good.

But it involved certain more subtle and obscure strains which I find myself hoping, for your own sakes, you may be spared. I am speaking here of war as a subjective experience for people of a given age group. In war, as in no other human undertaking, the modern form of popular nationalism rises up to assert itself as the dominant political force in our times. It brooks no questioning in these moments. It leaves no room for those people (and they are fortunately few) who might prefer a narrower or a wider sphere of group loyalty. I am not disputing the necessity and inevitability of all this.

But never, it seems to me, does nationalism present itself in a cruder or more primitive form than in these moments of military contest. It is as though it were asking that it be loved and worshipped in its ugliest aspect. Of its own subjects it demands great idealism, faith, heroism, selflessness. But it comes, itself, as the embodiment of all that is violent and unreasoning and primitive. It comes with cliches and stereotypes and over-simplifications: with an entire body of legend and rationalization which future historians refer to as war hysteria.

In this last war, as in all modern total wars, it proved difficult for people to view war for just what it was: a tragedy for victors and vanquished alike, a failing of the processes of civilization for which we were all in some degree responsible. It proved difficult to bear in mind, amid the hubbub of wartime autosuggestion, that in the actions of great masses of people there could be no absolute moral right and no absolute moral wrong: that such actions were understandable only in terms of human nature as it is and as it cannot help being; and that therefore moral indignation was beside the point in these questions. People failed to realize that war in itself could bring nothing positive—that the best it could be would be to give to us, rather than to our opponents, physical survival and responsibility for the reconstruction of life in a world vastly worsened by bloodshed and destruction. Perhaps it is impossible for a great nation to fight a war sadly, and with humility, bearing in mind the tragic and negative nature of the project itself, and yet producing out of its midst the heroism and spirit of sacrifice necessary for victory. Perhaps it is too much to ask that men should be prepared to die for something which is only a sad necessity and not a great and glorious venture—that they should be asked, in other words, not only to avenge the crimes of our enemies but also to expiate the failings of ourselves. But if this is true, it is a significant fact about war itself; and we should then remember that we cannot fight a war without corrupting our own understanding of reality and thereby damaging ourselves.

In any case, our generation went to war, as another generation had done before us, surrounded by all sorts of delusions: delusions about our enemies, about our allies, about ourselves, about the nature of the problems which required correction, and about the possibilities of war itself to act as a corrective. In some of these things we believed; in others we didn't. But in any case they beclouded our vision; and again, as had been the case with another generation before us, in our effort to adjust to the tasks of a postwar world we found ourselves hampered by the abuse we had inflicted upon our own understanding of the realities of our time. This handicap was to find its expression later in a widespread distrust of all political thought, in a revulsion to intellectualism as such, which was one of the hallmarks of the post-hostilities period.

With the conclusion of the war, we had been out of college for 20 years. In the postwar world we had a greater possibility than ever before to free ourselves for participation in public life. Our positions were better established, our children were growing up. Many of us found ourselves, for the first time, being asked to assume responsibility for public affairs.

You have all been through the Great Issues Course here at Dartmouth. You know the nature of the problems which have loomed before this country since the recent war came to an end. You must realize that these problems are new and strange to a degree that problems have rarely been for any previous generation; that they were ones little foreseen or provided for by the founders of our American civilization; and that they enforce upon us the necessity of great and difficult improvisations.

They often seem to us to involve more than just questions which can be solved by logic and the slide rule. They seem to involve genuine dilemmas, to which no clear solutions are visible.

These dilemmas revolve around the relationship of individual man to organized society. Bigness and complexity are erecting ever higher pinnacles of demand on human management: on the physical, nervous and moral strength of the individual manager. Contemporary science has shown how much more easily the mass of men may be influenced by their subconscious emotional responses than by their reason. Never was there a greater temptation for individual men, taking advantage of this new knowledge of human behavior, to set themselves up in positions of authority and to manipulate the masses of their fellow men as though they were not men at all, but beasts, easily herded around by appeals to their reflexes. The totalitarians have already done this; and many of us cry out against it, for we feel that it harbors something false and infinitely sinister; that the men who set themselves up as gods in this way are only fallible mortals themselves; and that they must eventually drag great masses of people down with them in the collapse made inevitable by their own fallibility. And yet behind us there is something else which whispers in our ear that man's command over the forces of nature is today imperiling the very environment on which he depends for the continuation of life, and that unless individual men can find in themselves the greatness and the courage to step forward and to take on godlike responsibilities and fulfill them with selflessness and compassion toward their fellow men, as Christ once fulfilled His, our civilization may be facing an early and a fearful end.

It is in the consciousness of these dilemmas that we now walk, in this year 1950. We need not take this too dramatically or too tragically. It has always been man's fate to walk in the presence of some questions he could not resolve. We are beginning to realize that there will be no a priori resolution of these or any other of the great dilemmas of our time: that they will find their answers in the world of action and of change—as Justice Holmes once said of thoughts that they found their worth in the market place of ideas.

In this way it is beginning to seem to some of us that perhaps what is of decisive importance in our world is not the "what" but the "how"; that the goal of human endeavor may be beyond the horizon of man's vision or comprehension but that it will be a better goal or a worse goal depending on the methods we employ to seek those things which instinct and taste and conscience tell us to seek; and that perhaps for that reason we should not preoccupy ourselves excessively with the purposes of effort but should try to assure ourselves primarily that the methods by which we conduct it are ones which our own souls can live with.

It is this conviction on the part of some of us which lends such great meaning in our eyes to the controversies now agitating our public life over such things as loyalty and political reliability, on the one hand, and freedom of thought and expression, on the other. It is not so much a question of the things men wish to do, but in the question of the methods by which they strive to do them some of us see an issue of great profundity and rare clarity. It is possible that our generation may become badly split over this issue. That will be a painful and unhappy thing. Yet I cannot find it in my heart entirely to regret it. It is good to have a real issue in life: to know what one really believes in; to have those things which one detests drawn off, as though by a process of catalysis, to a single pole where one can identify them and oppose them without hesitation. Freedom itself, for some reason, is never so beautiful as when its existence is threatened, and when the shadows of its enemies fall across its face, giving depth and contrast to its features.

Moving among these problems and issues, many of us in my age group are aware that history is placing great demands upon us—that it is calling upon us for the seriousness and selflessness and insight commensurate with the great occasions. We know that we are only partially adequate to these demands; that we lack the spiritual and intellectual training which might have fitted us to meet them, that we have come to them largely as a dilettante generation; unschooled, unhardened, unshaped by experience. We are still embarrassed and held back by the outward normality of the setting in which we have to work: by custom and faint-heartedness, and the habit of self-interest. We know that the framework of our lives is still uncongenial to quietness and contemplation, uncongenial to the gathering of thought and energy rather than to their dissipation. In the face of these deficiencies we are carrying on in the ways that we know how.

When we look backward over the years, we do not regret either the pain or the laughter—either the anguish of struggle or the enjoyment of the good things of life. We regret only the empty moments, marked neither by anguish nor by happiness: the moments wasted in pretense, in hypocrisy, in the doing of things which were not important, in the effort to be things which we were not, and to fulfill functions which we were not designed to fulfill.

In 1975 you will be standing in our places looking backward, as we do, over a quarter of a century of the effort of maturity. Some of you may wonder now what is the relevance of that which I have told you to those experiences that lie ahead.

I cannot give you the answer to this question. The time when you could look to others to tell you the meaning of the phenomena of this world is passing with this hour and with this occasion. From now on, you are on your own. If this occasion has reinforced in your minds this single realization, it will have justified itself and the category of human events to which it belongs.

ROBERT D. KILMARX SAYS FAREWELL TO THE COLLEGE FOR THE CLASS OF 1950

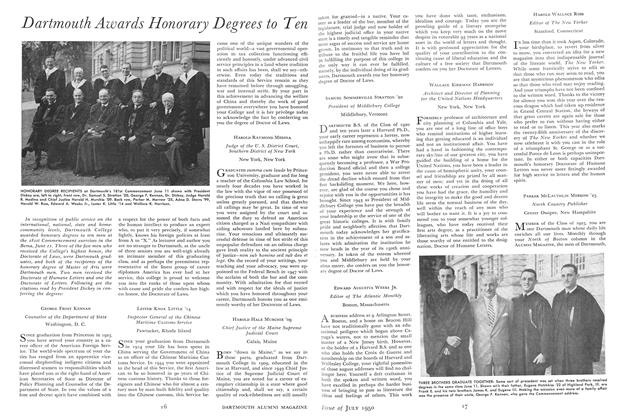

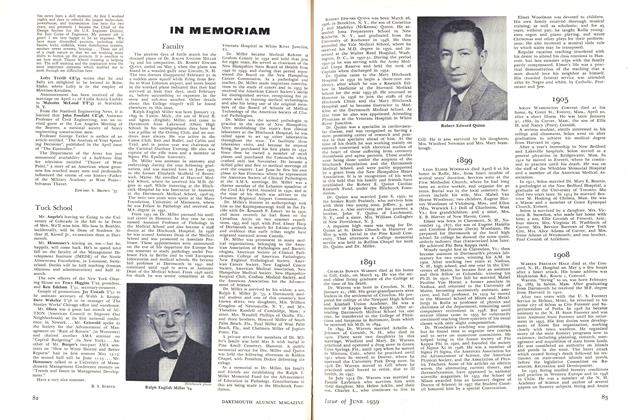

BACCALAUREATE SPEAKER: George F. Kenncm (right), who gave the principal Commencement address, shown with Judge Harold R. Medina. Both received the honorary Doctor of Laws degree.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1950 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleThe 181st Commencement

July 1950 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940's Fast and Furious 10th

July 1950 By JUDSON S. LYON '40 -

Class Notes

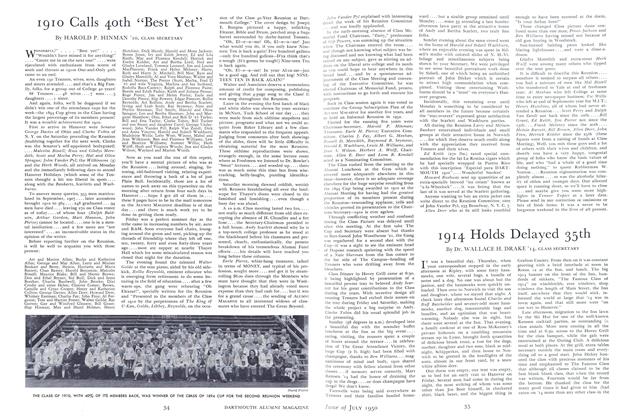

Class Notes1910 Calls 40th "Best Yet"

July 1950 By HAROLD P. HINMAN '10 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Awards Honorary Degrees to Ten

July 1950 -

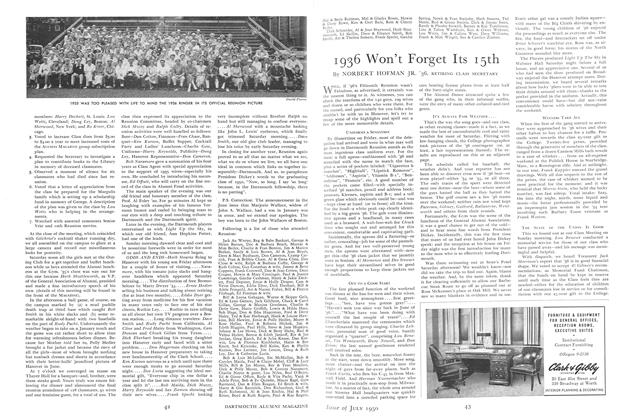

Class Notes

Class Notes1936 Won't Forget Its 15th

July 1950 By NORBERT HOFMAN JR. '36

Article

-

Article

ArticleBACK FILES OF ALUMNI MAGAZINE DESIRED

June, 1923 -

Article

ArticleQueen of the Snows Chosen

MARCH, 1928 -

Article

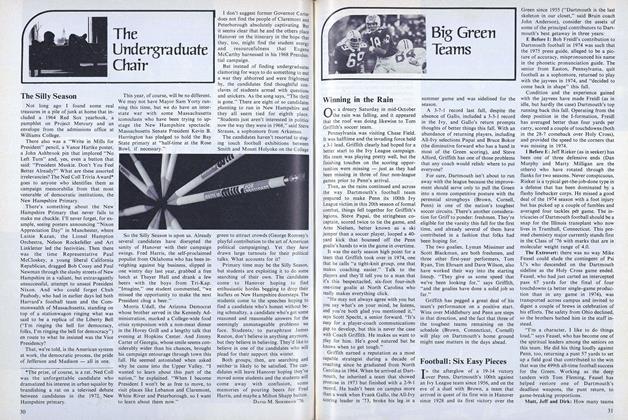

ArticleProposed Mew Webster Hall

December 1938 -

Article

ArticleWinning in the Rain

November 1975 -

Article

ArticleIntroduction—My Year as A Senior Fellow

April 1933 By Kimball Flaccus '33 -

Article

ArticleTuck School

JUNE 1959 By R.S. BURGER