COLLEGE FORESTER

DANIEL WEBSTER was not the first Dartmouth alumnus to climb Mount Washington. But the circumstances of his pilgrimage to the heights 120 years ago properly qualify him as a forerunner of the parade of Dartmouth alumni who have been associated through the years with the summit of our highest New England peak.

In 1831, thirty years following graduation, Dan was approaching the height of his career—his "Reply to Hayne" was delivered the previous year. The cards were falling his way. So it must have been a rather disillusioning personal experience to climb to the summit and, like King Canute, have the elements refuse to do his bidding.

Declared Black Dan, with prose that has persisted to this day in the literature of the White Mountains: "Mount Washington, I have come a long distance, have toiled hard to arrive at your summit, and now you seem to give me a cold reception, for which I am extremely sorry, as I shall not have time enough to view this grand prospect which now lies before me, and nothing prevents but the uncomfortable atmosphere in which you reside!"

His guide, the venerable Ethan Allen Crawford, was no courthouse reporter, but the above quotation which he faithfully recorded reads like a typical Websterian apostrophe. Crawford must have been dismayed, as would any respectable guide when he cannot produce a memorable trophy or mountain view for a famous "sport," but whatever chagrin he may have felt probably vanished when his distinguished client paid the bill for his party's lodgings and meals and made him "a handsome present" of twenty dollars.

Webster may have imagined that in the years to follow numerous undergraduates, faculty members and alumni would return to study and to adventure in the "uncomfortable atmosphere" of which he complained, even in June.

But little did he suspect that 120 years later his cherished Alma Mater, whose independent destiny he had assured in the Dartmouth College Case, would find itself the sole owner of the summit of Mount Washington.

At the southwestern rampart of the Presidential Range, along the precipitous ledges that flank Crawford Notch opposite the site of the Willey House, lies Mount Webster. Dan didn't quite make the White House, but at least this outlying mountain identified by his name is embraced by the Presidential Range for all time.

Many other Dartmouth alumni followed Webster's trail to the heights, but perhaps the most audacious was a frustrated school teacher, Jonathan Marshall, 1854, who is regarded as the first individual to consider occupying the summit during winter for scientific purposes. He received encouraging support from the Smithsonian Institution and obtained permission from property owners to occupy one of the summit buildings. An early snowstorm upset his plans, but he deserves some credit for even considering the idea because the first winter ascent of record occurred in December 1858, only one year before he planned to occupy the summit for the entire winter, and not until 1862 did anyone spend a winter night atop Mount Washington.

Directly after Dartmouth's 1869 Centennial, President Asa Dodge Smith headed a group of twelve faculty members bent on visiting the summit at the invitation of the distinguished White Mountain landlord, Col. Asa Barron, who was the caterer at the Hanover festivities. The village wit observed that the invitations were given "to take off the cuss of the dinner."

Upon descending the mountain, President Dodge's party" met General Grant about to set forth on a similar pilgrimage. What the President of the College may have said to the President of the United States is not generally known, but the greetings were probably not very cordial. President Smith lost, his spectacles in a sudden gust of wind at the summit, causing his son to report, "Thereafter the scenery interested him no more." Professor Sanborn was nursing the colic, another member of the ill-fated group had a violent and unexplained illness, and the relative comfort of the Hanover Plain was probably uppermost in their minds.

When the summit was first "occupied for scientific purposes, it was under the supervision of Professor C.H. Hitchcock, State Geologist and Hall Professor of Geology and Mineralogy at Dartmouth from 1868 to 1908. During that memorable winter of 1870-71, the only dependable link the pioneer summit observers had with the outside world was through Professor Hitchcock's office in Culver Hall, then under construction but since obliterated from the Hanover scene.

Thrice weekly, when the day's business was done, obliging railroad telegraphers at Littleton and Wells River threw switches that connected Mount Washington with Hanover in one continuous circuit. The equally accommodating Hanover telegraph operator and postmaster arranged for an extension to Professor Hitchcock's office and aided the college amateurs in deciphering the mountain messages.

As S.A. Nelson, summit observer and fund-raiser of the expedition, explained in the official record of the Observatory, "Receiving telegraphic news from Paris, as soon as people in the seaboard cities, was not an uncommon occurrence. News thus received has a flavor to it that people who have the daily papers cannot appreciate."

With the organization of the Dartmouth Outing Club in 1909-10, it was only natural that its members should find in Mount Washington a qualified challenger for any adventurer. By 1913 the summit was first reached on skis (but without poles not then in vogue) by a Dartmouth group—Fred H. Harris '11, Club founder; Carl Shumway '13, its third president; and Joseph Cheney '13.

Throughout the twenties and thirties the Club organized winter expeditions to the summit via the Carriage Road and Tuckerman Ravine, at first basing on the Glen House or Ravine House and, from 1927, on the Appalachian Mountain Club's headquarters at Pinkham Notch Camp. Snowshoes for climbing above treeline and homemade creepers (later improved crampons) for the icy, windswept stretches above timber were the modus operandi until skis and sealskins took over about 1930.

The Senior Mount Washington Trips, on Town Election Day weekend, promoted by Richard J. Lougee '27, an exponent of the Cog Railroad route from the west, were popular for awhile until that holiday was dropped from the college calendar and skiers turned to slopes served by lifts and tows for their enjoyment.

In recent years fall excursions to the heights for a preview of winter have proved more popular than climbs in mid-winter, when downhill-only skiing is available elsewhere.

Of the hundreds of Dartmouth undergraduates who had scrambled over the Presidential Range in fair weather and foul, it is notable that the first fatality did not occur until December 1, 1928, when a freshman, Herbert Judson Young, reached the end of his trail on the south bank of the Ammonoosuc River about a mile toward Mount Washington from the Base Station, when a D.O.C. Thanksgiving trip missed its storm-hidden objective at the Lakes of the Clouds Hut and descended to safety for all but one in the protected depths of the Ammonoosuc Ravine.

Despite the numerous Mount Washington casualties, this was the first instance of a climber perishing in a winter month and the first time a member of an organized climbing party failed to return. Two Dartmouth students later lost their lives on Mount Washington outings not sponsored by the D.O.C.

When the cautious editor of a now-defunct Boston daily wrote, "It is indeed foolish for young persons, or for those not highly trained in mountaineering effort, to defy the winter conditions of even a mountain no higher than Washington," President Hopkins replied at some length, concluding, "The real fact is that the college or the country or the age which combats the influence of every lure which challenges to physical achievement will, I believe, become anemic and uninspiring in all things."

A host of Dartmouth students found summer jobs as well as college-year adventure on the rugged slopes of Mount Washington, especially when Paul R. Jenks '94 and Nathaniel L. Goodrich, retired College Librarian, were directing the ambitious trail program of the Appalachian Mountain Club. Others manned the several huts operated by the same club in the high country.

Over the years many Dartmouth professors have used Mount Washington as a fertile field for their own observations and as illustrations for classroom discussions. The late Prof. James W. Goldthwait typified this educational use of the mountain's lessons. He studied its glacial cirques, terminal moraines, and other evidences of the invasion of New Hampshire's highest elevation by the Canadian ice sheet, reporting his conclusions in The Geology of NewHampshire (1925).

It remained for his son, Prof. Richard P. Goldthwait '33, to substantiate his father's contention that the ice sheet covered Mount Washington "after local glaciation at such landmarks, as Tuckerman Ravine. As reported in Goldtliwait's Geology ofthe Presidential Range f the excavation in 1937 for the Yankee Network tower proved a geologist's paradise;

The real genesis of the Mount Washmgton Observatory, which has operated daily from October 1932 to the present, occurred during the college Christmas recess of 1926, when a quartet of Dartmouth adventurers (Prof. Warren E. Montsie '15; Louis C. Conant '26, at that time instructor in geology; Harold H. Leich 29; and the author) undertook a three-day stand in Camden Cottage, a summit refuge structure built in 1922 and now part of the Summit House.

Numerous instruments, including an anemometer loaned by the late Prof. John Poor, were back-packed over the soft December snow in Tuckerman Ravine. At our invitation, Joe Dodge, then operating the A.M.C. Camp at Pinkham Notch for its first winter, joined the group during part of our sojourn and immediately became interested in our elementary observations.

At that time and on later occasions, Dodge and I discussed the possibility of a full-winter occupation of the summit for scientific purposes. The spark did not strike until 1931, when The New YorkTimes and later the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society announced plans for the Second International Polar Year to be observed in the winter of 193233, the fiftieth anniversary of the First International Polar Year. Stations at high altitudes and latitudes were to be estabPainting, lished by 27 participating nations. If the summit was to be occupied during our more able years, the winter of 1932-33 was the time!

The Danish president of the Polar Year Commission stated, "Certainly the observations from Mount Washington would mean a very valuable contribution to the continued watch of what takes place in the upper air."

The two American members of the Commission endorsed the Mount Washington project, but all of the $30,000 appropriated by Congress had already been earmarked for the two special stations at Fairbanks and Point Barrow, Alaska.

Spirits were still high, but funds were low in that third year of the depression. Then, at the crucial point in May 1932, the New Hampshire Academy of Science, after a resume by Joe Dodge of the project as then conceived, passed a motion intro.

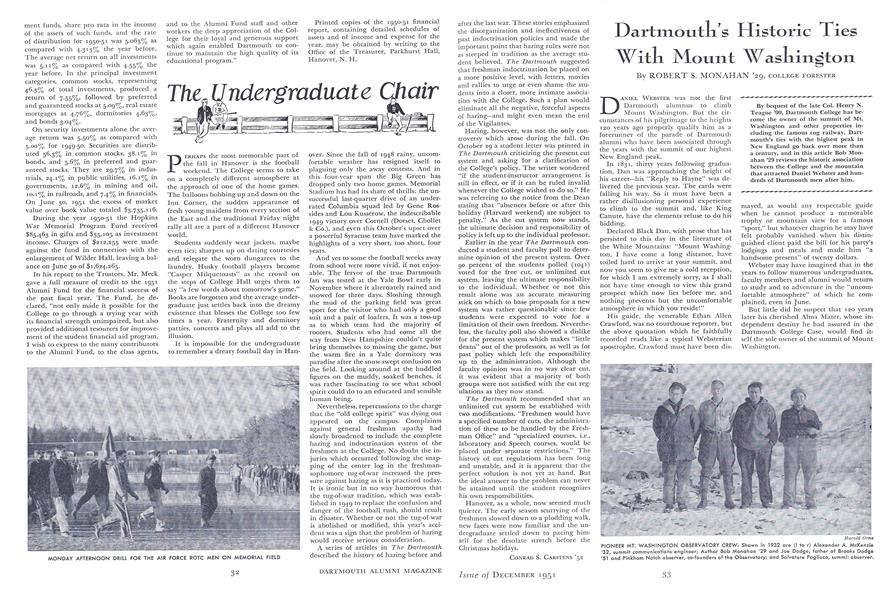

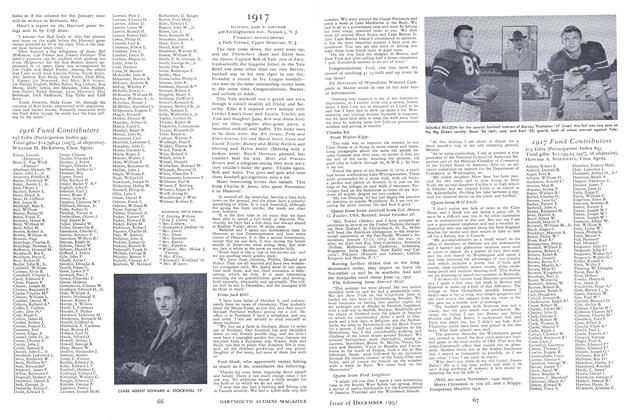

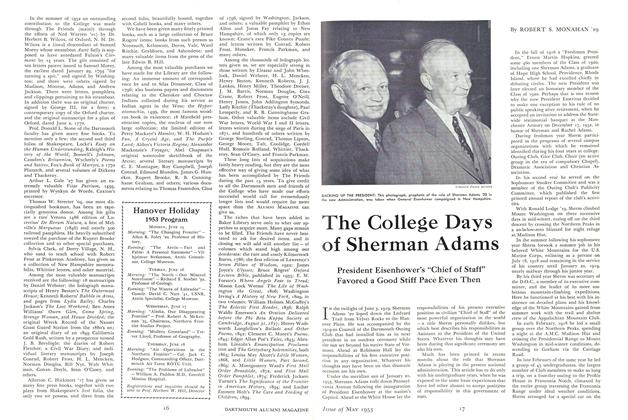

PIONEER MT. WASHINGTON OBSERVATORY CREW: Shown in 1932 are (I to r) Alexander A. McKenzie '32, summit communications engineer; Author Bob Monahan '29 and Joe Dodge, father of Brooks Dodge '51 and Pinkham Notch observer, co-founders of the Observatory; and Salvatore Pagliuca, summit observer.

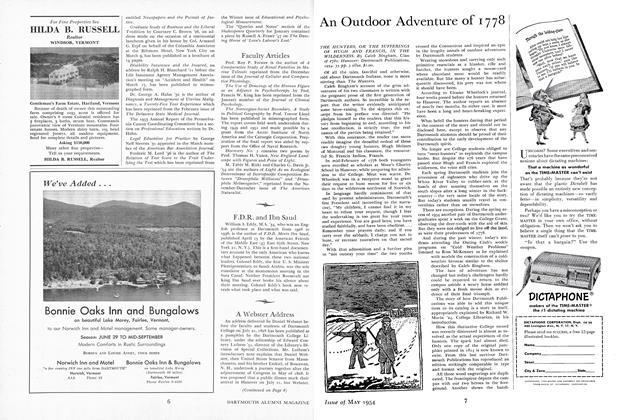

END OF THE LINE: A winter view of the end of the Mt. Washington Cog Railway, showing the frost feathers created by strong winds at the summit.

By bequest of the late Col. Henry N.Teague '00, Dartmouth College has become the owner of the summit of Mt.Washington and other properties including the famous cog railway. Dartmouth's ties with the highest peak inNew England go back over more thana century, and in this article Bob Monahan '29 reviews the historic associationbetween the College and the mountainthat attracted Daniel Webster and hundreds of Dartmouth men after him.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

December 1951 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

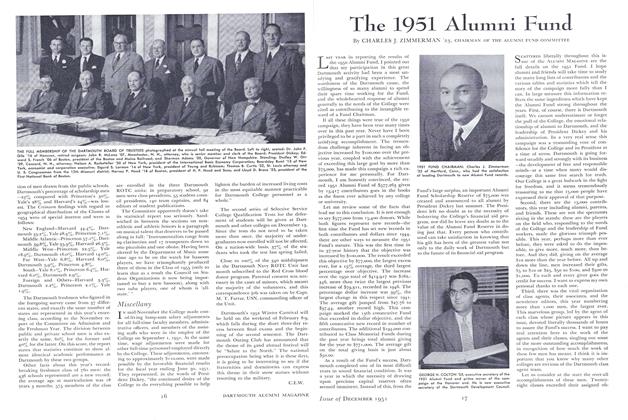

ArticleThe 1951 Alumni Fund

December 1951 By CHARLES J. ZIMMERMAN '23 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

December 1951 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, JACK D. GUNTHER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

December 1951 By ENS. SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

December 1951 By HENRY R. BANKART JR., JOHN WALLACE, SIDNEY A. DIAMOND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1946

December 1951 By REGINALD F. PIERCE JR., ROBERT Y. KIMBALL

ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

APRIL 1978 -

Article

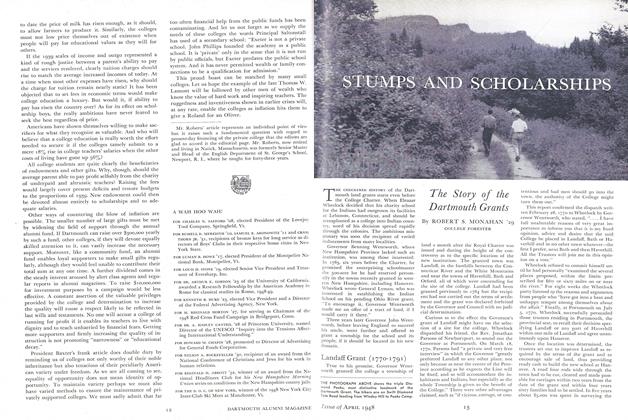

ArticleStumps and Scholarships

April 1948 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Article

ArticleThe College Days of Sherman Adams

May 1953 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Article

ArticleAn Outdoor Adventure of 1778

May 1954 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Books

BooksAMOS JACKMAN.

February 1958 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Feature

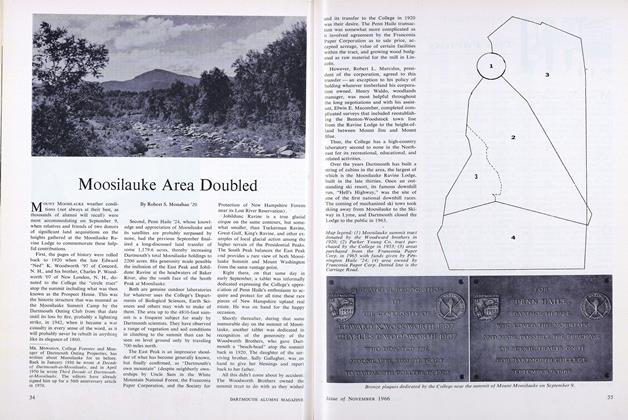

FeatureMoosilauke Area Doubled

NOVEMBER 1966 By Robert S. Monahan '29