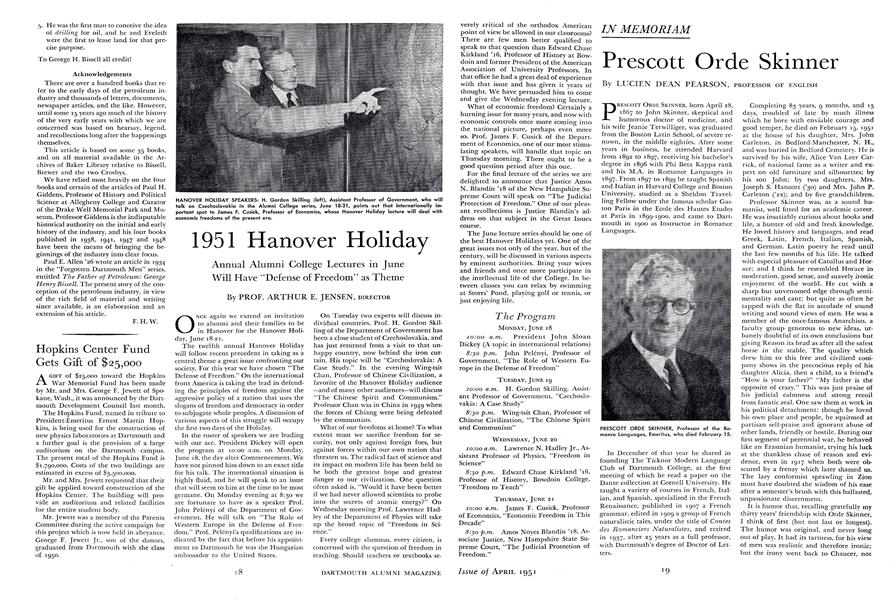

PRESCOTT ORDE SKINNER, born April 28, 1867 to John Skinner, skeptical and humorous doctor of medicine, and his wife Jeanie Terwilliger, was graduated from the Boston Latin School, of severe renown, in the middle eighties. After some years in business, he attended Harvard from 1892 to 1897, receiving his bachelor's degree in 1896 with Phi Beta Kappa rank and his M.A. in Romance Languages in 1897. From 1897 to 1899 he taught Spanish and Italian in Harvard College and Boston University, studied as a Sheldon Travelling Fellow under the famous scholar Gaston Paris in the Ecole des Hautes Etudes at Paris in 1899-1900, and came to Dartmouth in 1900 as Instructor in Romance Languages.

In December of that year he shared in founding The Ticknor Modern Language Club of Dartmouth College, at the first meeting of which he read a paper on the Dante collection at Cornell University. He taught a variety of courses in French, Italian, and Spanish, specialized in the French Renaissance, published in 1907 a French grammar, edited in 1909 a group of French naturalistic tales, under the title of contes des Romanciers Naturalistes, and retired in 1937, after 25 years as a full professor, with Dartmouth's degree of Doctor of Letters.

Completing 83 years, 9 months, and 13 days, troubled of late by much illness which he bore with enviable courage and good temper, he died on February 15, 1951 at the house of his daughter, Mrs. John Carleton, in Bedford-Manchester, N.H., and was buried in Bedford Cemetery. He is survived by his wife, Alice Van Leer Carrick, of national fame as a writer and expert on old furniture and silhouettes; by his son John; by two daughters, Mrs. Joseph S. Hancort ('30) and Mrs. John P. Carleton ('22); and by five grandchildren.

Professor Skinner was, as a sound humanist, well fitted for an academic career. He was insatiably curious about books and life, a hunter of old and fresh knowledge. He loved history and languages, and read Greek, Latin, French, Italian, Spanish, and German. Latin poetry he read until the last few months of his life. He talked with especial pleasure of Catullus and Horace; and I think he resembled Horace in moderation, good sense, and suavely ironic enjoyment of the world. He cut with a sharp but unvenomed edge through sentimentality and cant; but quite as often he tapped with the flat in accolade of sound writing and sound views of men. He was a member of the once-famous Anarchists, a faculty group generous to new ideas, urbanely doubtful of its own conclusions but giving Reason its head as after all the safest horse in the stable. The quality which drew him to this free and civilized company shows in the precocious reply of his daughter Alicia, then a child, to a friend's "How is your father?" "My father is the opposite of crazy." This was just praise of his judicial calmness and strong recoil from fanatic zeal. One saw them at work in his political detachment: though he loved his own place and people, he squirmed at partisan self-praise and ignorant abuse of other lands, friendly or hostile. During our first segment of perennial war, he behaved like an Erasmian humanist, trying his luck at the thankless chase of reason and evidence, even in 1917 when both were obscured by a frenzy which later shamed us. The lazy conformist sprawling in Zion must have doubted the wisdom of his ease after a semester's brush with this ballasted, unpassionate discernment.

It is humor that, recalling gratefully my thirty years' friendship with Orde Skinner, I think of first (but not last or longest). The humor was original, and never long; out of play. It had its tartness, for his view of men was realistic and therefore ironic; but the irony went back to Chaucer, not: Swift, and was tempered by a genial, uncarping relish of the day's work and talk and relaxing fribbles. He liked people, savoring their company over Main Street coffee; over sherry in their houses; over the distinguished victuals that for five decades made his wife's table famous; on the street, where one felt his flattering pleasure in the meeting; or on his habitual great walks. Many of us will recall, with regret for small things familiar and lost, his daily five miles with the late Louis Dow and Professor Ernest Greene, the ineluctable march of The Three Discursive Walkers. In all ways he enjoyed being alive; more, I believe, than most of us. He told me once, with a sudden vigor lightened by self-mockery, that he wanted never to die: life was too much fun. This was not the serenity of a sheltered and academic innocence; he knew better than many the perturbations of our dust, but he was too much for them. Without apparent fear, he refused for 15 years the often urgent solicitation of death, shoring up his frailness with .a buttress-work of curiosity and delight in the world: in its men, books, and enormous, inexhaustibly amusing show.

Acquaintances will remember best Orde Skinner's humor, or gaiety, or judicial mind, or hospitality. His friends will think last and longest of his warm and cheerful affection. His temper was unique in my experience. It is no stretch of truth to say that he was always considerate and indulgent; in thirty years I never saw him sullen, peevish, harsh in moral judgment, spiteful, or angry. His nature was open, expansive, and though bookish too, gregarious. He made no conscious effort, I think, toward the social virtues; but he had them rarely.

For us too it will be no effort to summon up remembrance of this good colleague and good man, who has colored, garnished, and amplified our lives by his humor, his intelligent curiosity, the fine balance of his humanistic culture and his gift of undemanding constancy in friendship.

PRESCOTT ORDE SKINNER, Professor of the Ro- mance Languages, Emeritus, who died February 15.

PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleIt All Began in Hanover

April 1951 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Article

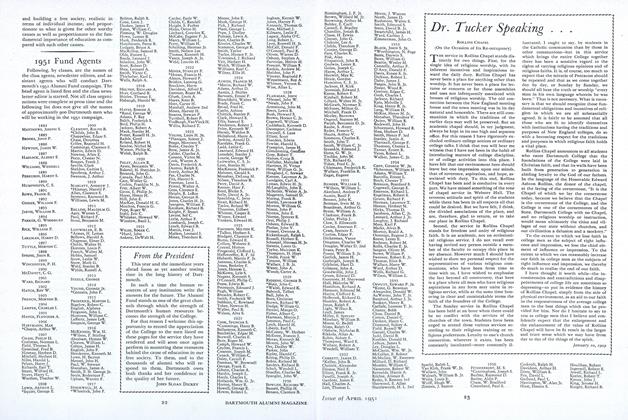

Article1951 Fund Agents

April 1951 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. EARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

April 1951 By ROBERT H. ZEISER, DAVID S. VOGELS JR., JOHN F. STOCKWELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

April 1951 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART 3RD, LEON H. YOUNG JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

April 1951 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, SARGENT F. EATON, MALCOLM G. ROLLINS