MUSIC AND THE MUSICIAN IN JEANCHRISTOPHE, THE HARMONY OF CONTRASTS.

MAY 1969 LUCIEN DEAN PEARSONBy David Sices '54. NewHaven and London: Yale University Press1968. 189 pp. $6.50.

This is a learned, soundly critical, and well documented work, whose author I remember as a brilliant student in the 1950's. He studies the influences on Rolland's conception of music and how it enters the character of Jean-Christophe Krafft and the famous novel that bears his name.

From Spinoza, Rolland took the notion of life as a river eternally flowing and dominated by a life-force, to which his own life responded with a vigorous creative ardor, music and his novel too he saw as part of life's river. This is the period of heroic individualism in author and composer.

From Renan, Rolland learned that the road of self-realization is not straight but zigzag, lost and found again. This influence is strengthened by Goethe's "stirb und werde": that is, dying to one stage of growth is followed by a leap ahead toward final harmony as dissonance is resolved in music. „

By Tolstoi, Rolland was led astray to a social and democratic view of music, which as in Tolstoi's What Is Art? should reach all manner of men and feed their souls. Forced by his rejection of music for the elite, Jean-Christophe leaps backward over the nineteenth century to Handel, his one examplar from the past. But disillusioned with the human mass by experience of revolution, he springs from the Tolstoian bog to the firm ground of his final view of music. Music now is nourished by artistic aristocrats and voices universal and eternal things above the laws of a day and is freed from social doctrine.

From this point on, I miss the full clarity of the previous chapters, but this is what I think the author meant. The finale of Jean-Christophe aims to reconcile the seeming contrasts in the life and work of the composer through what is constant in his nature and ambition. The irregular progress in thought and music through the turbulence of passion and conflict shows at each stage the same violent creative force and bold and independent will to greatness.

And why is Jean-Christophe a musical novel?

First, our critic writes, "Breadth of scope is an attribute of the essential musical quality of the novel"; and Jean-Christophe has, beyond question, breadth of scope.

Further, "The shape of Rolland's novel is an architecture based on the intersection of theme, rhythm, conflict, and plastic line," as a Beethoven symphony is built on motif, rhythm, harmony, and development. "It is in this way that Jean-Christophe may be seen as a musical novel." And again, "A musical novel should be the flowering of a sentiment which is its soul." (But are not such form and such unfolding, structural qualities of all novels that we judge as art?)

However this may be, Mr. Sices has illumined for us the life and thought and art of a great Frenchman who without denying his race became a great European.

Mr. Pearson is Professor of English, Emeritus, Dartmouth College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMutual Sensitivity Wins the Day

May 1969 By JOHN DICKEY -

Feature

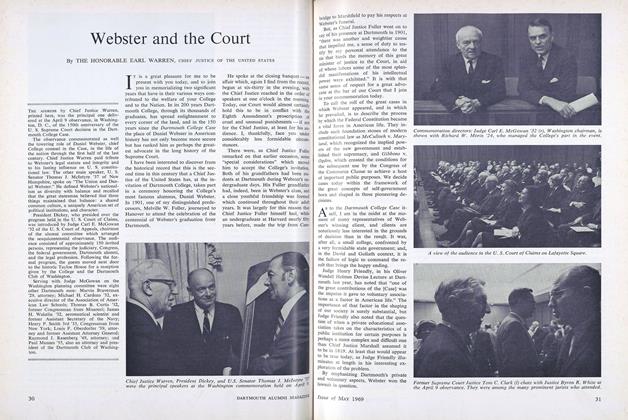

FeatureWebster and the Court

May 1969 By THE HONORABLE EARL WARREN -

Feature

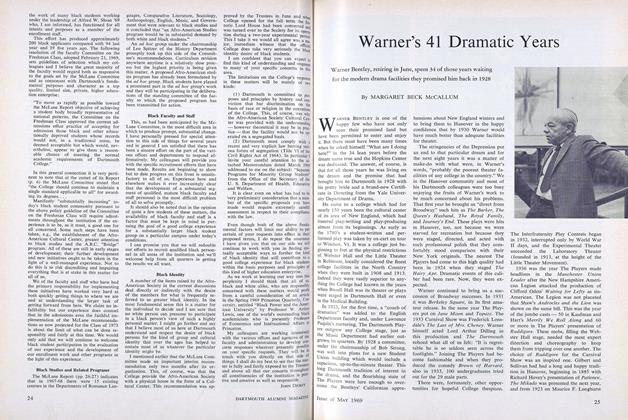

FeatureWarner's 41 Dramatic Years

May 1969 By MARGARET BECK McCALLUM -

Feature

FeatureMay 17 Event to Salute Eleazar's Starting Point

May 1969 -

Books

BooksERNEST HEMINGWAY: A LIFE STORY

May 1969 By JEFFREY HART '51 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1969 By CHRIS KERN '69

LUCIEN DEAN PEARSON

Books

-

Books

BooksROBERT SALMON: PAINTER OF SHIP & SHORE.

DECEMBER 1971 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksSustainable Resources

JUNE 1982 By Denis L. Meadonws -

Books

BooksLOVE MATCH AND ARRANGED MARRIAGE, A TOKYO-DETROIT COMPARISON.

NOVEMBER 1967 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Books

BooksTHE NAKED WARRIORS.

November 1956 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksCHINESE INFLUENCE ON EUROPEAN GARDEN STRUCTURES

April 1937 By Walter Curt berhrendt -

Books

BooksTHE CLASH OF POLITICAL IDEALS

January 1941 By Wm. K. Stewart