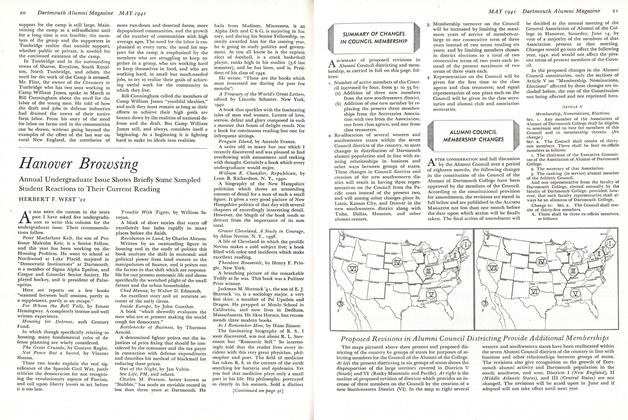

ONE sees a great many articles these days disparaging the modern college student. He is said to be docile, lacking in initiative, and interested only in security. We are told that he is afraid of taking any kind of risk, that he is immune to intellectual adventure. And the gloomy conclusion usually reached is that our country's future is in grave jeopardy unless we quickly recast our undergraduates in a new mold—a mold which bears suspicious resemblances to one version or another of "the good old days." Such articles are seldom written by practicing teachers, and it seems to me they can usually be dismissed as mildly hysterical hogwash. From where I sit, facing Dartmouth undergraduates daily in class and conference, the crisis seems a trifle less desperate, and the student, for all his faults, comes off with a fairly clean bill of health.

Of course no single teacher's impression of his students will agree in all details with his colleagues' views. His information is limited by his individual teaching techniques, his subject matter, and the small segment of the undergraduate body he happens to encounter. Moreover, the student himself resents all attempts to generalize about him, to categorize him, a healthy sign. However, accepting these limitations, here are one teacher's impressions of his students today.

In class their appearance and behavior are much the same as in recent decades. The uniform is still defiantly informalmostly baggy slacks and sweaters—and the manner is still a contrived casualness. Before the hour they argue and laugh, or check hurriedly over their notes. As the bell rings, the latecomers slip in, the din subsides, and a submerged groan greets the announcement of a quiz, or the hands shoot up in response to the first question of a recitation exercise.

They are generally well-mannered and attentive in class. Of course some are more eager to talk than others, taking fast shots in the dark or dealing off the tops of their minds, and it often turns out that the shy, quiet ones knew the answers. Beginning freshmen tend to start with poised pencils, expecting to get The Word straight from the horse's mouth, and are shocked or embarrassed when they find that the horse wants them to put down their pencils and tell him. As their ideas uncurl, it becomes plain that their minds are lively and inquiring, and they soon learn to keep a teacher on his toes. Nor is there anything wrong with their sense of humor. Let someone utter an unintentional doubleentendre, and the roof quickly falls in on him.

When first summoned to your office for individual conferences, they knock hesitantly and come in stiffly, on the defensive, but most of them are readily disarmed, will- ing to acknowledge their weaknesses and honestly eager to have help in correcting them. By the end of a half hour many of them loosen up so much that you have trouble getting rid of. them when their time is up; some unburden themselves with alarming candor on all sorts of subjects, and you are lucky if your profession, your college, and even your own course and your method of teaching it survive the deluge when the floodgates break. A few keep coming back, but most of them prefer to try and work things out for themselves.

Of course the central question is this: just how much real intellectual energy and curiosity do they have? The occupational disease of the professor is chronic dismay at the lack of independent enthusiasm for his subject that he finds in most students. In his worst moments he wonders whether the admissions office, in its quest for the well-rounded man, isn't rounding off the bump of intellectual tendency somewhere in the process, and winding up with Jack Armstrong. It can be disquieting to be told in a large number of freshman themes at a liberal arts college that the authors are enrolled for the primary purpose of participating in athletics or preparing themselves to earn more money. But the professor's concern is often just a symptom of his own passionate love of his subject, and the student's diffidence is partly the natural human resistance to the process of getting educated.

The students are fully as intelligent and as interested today as they have been in the past. The competition for admission has become stiffer, and the standards have gone up. Students have to work harder today. I am frequently astonished at the quantity and quality of work some students are capable of doing, even when left to their own devices. They can tackle the most difficult assignments with enthusiasm, and often go out of their way to find extra work and to pursue their own interests, even when heavily burdened with valuable extra-curricular activities. In short, the misconceived objectives are eventually abandoned, and the real learning process is begun.

The veteran student was much praised because "he knew what he wanted." The trouble was that in terms of a liberal arts education he too often wanted the wrong things, looking on college too narrowly, as a mere utilitarian preparation for his future job. The younger student of today has a mind more open and flexible, and hence perhaps more educable.

Of course all is not milk and honey. There are still men who come to Dartmouth with closed minds, and do their utmost to exclude all disturbing influences. There are loafers, there are those who want to be told what to think, and there are the grade-seekers, who view education as the delicate art of supplying what they think the professor likes. Nor are they all, or always, serious, alert, and polite. There is the perennial boy who asks his instructor on Thursday: "Sir. I'm taking off for the weekend; are you going to say anything important on Saturday?"

And just last week in one of my sections I was pointing out the symbolic values of a phrase in a Conrad story when a hand went up in the back of the room. "Doesn't Conrad use that expression again some- where else in the story?" the student asked. "X don't think so," I replied. "I'm sure he does," the boy persisted, riffling through the pages; "hold it a minute. Here it is (triumphantly), on page 346!" I looked at my book. "But page 346 is the page I was just talking about," I replied. A pause. "Oh-oh," the light dawned; "there seem to be two page 346's in my book." Turned out that the same fifty pages had been bound twice, into his volume and he had read all fifty twice without discovering it. It took about four minutes to restore order in the classroom after that one.

Another boy recently handed in a long written criticism of one of my favorite novels, Jane Austen's Emma, giving it some of the praise it deserves, but finally condemning it because, he felt, it ended so inconclusively. Taking issue with him on this point, I finally discovered that he had innocently read only the first volume of a two-volume edition, thinking that was the whole thing.

But it is important to realize that occasionally a student's shortcomings are forced upon him from without. If he tells you that he would like to take a particular course even though he knows he wouldn't do well in it, but that he is unable to take it because a low grade might injure his chances of acceptance in a graduate school or for a particular job, what can you say? If a student insists on specializing early, even in a liberal arts college, because the competition for positions after college demands it, whose fault is that? In many respects the society determines the quality of the student.

The present undergraduates deserve a great deal of credit for the way they have faced up to the uncertainties of their future, the draft and the war. Understandably restive when the Chinese entered Korea, wondering whether they would be able to complete their college courses, or even the academic year, they soon settled back to work and are finishing out the year in an atmosphere of calm determination to get the most out of college while they can, not stampeding to enlist and not by any means passively accepting their role as global warriors without question or without demanding to know the whys, but on the other hand not abjectly pitying themselves, not looking for the soft job or the easy way out, and not acting as if they were the first who have ever been asked to fight for their principles. When I compare their behavior with what I have heard of that on campus before the First World War and what I remember of that before the Second, I find them admirably balanced and mature.

In conclusion, let me remind the man who accuses these students of a timid preoccupation with security that for them a future of risk, travel, and sacrifice is virtually assured; what is not assured is the possibility that they will live long enough, or will be permitted to alight anywhere soon enough, to be 'able to contribute in any important constructive way toward a sane and peaceful world, which, I am sure, is what they all want most.

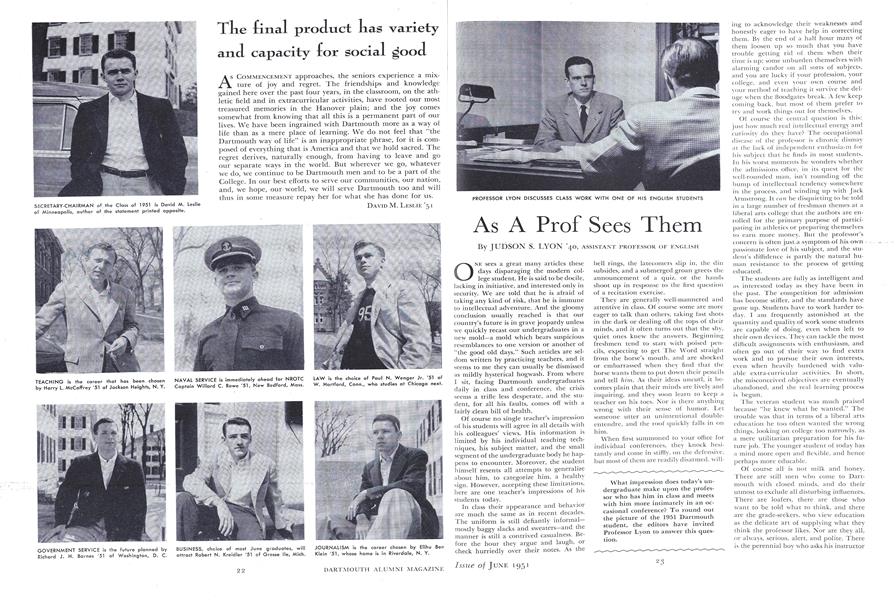

PROFESSOR LYON DISCUSSES CLASS WORK WITH ONE OF HIS ENGLISH STUDENTS

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

What impression does today's undergraduate make upon the professor who has him in class and meetswith him more intimately in an occasional conference? To round outthe picture of the 1951 Dartmouthstudent, the editors have invitedProfessor Lyon to answer this question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

June 1951 By ROBERT H. ZEISER, DAVID S. VOGELS JR., JOHN F. STOCKWELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARS, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

June 1951 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Article

ArticleThe Senior Fellowships

June 1951 By EDWARD C. LATHEM '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

June 1951 By ELMER T. BROWNE, DONALD G. RAINIE, FREDERICK L. PORTER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

June 1951 By ELMER G. STEVENS JR., STANTON B. PRIDDY, THEODORE R. HOPPER

Article

-

Article

ArticleNOTES

January, 1914 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah for –

JUNE 1969 -

Article

ArticleTrustee deliberations

APRIL • 1985 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP CHANGES

May 1941 By Bouchard -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH JOTTINGS OF A SOMEWHAT DESULTORY READER

February, 1924 By Fred Lewis Pattee '88 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

DECEMBER 1966 By GEORGE O'CONNELL