PRESIDENT HOPKINS had been devoting considerable thought to the manner in which the College might better serve the exceptional student. By exceptional he did not mean the student "who has simply shown an acquisitiveness for grades," nor necessarily the brightest or most outstanding undergraduate.

He was thinking, rather, in terms of men who possessed not only great ability and capacity for learning but also an uncommon degree of intellectual curiosity, initiative, and self-reliance; men whose interests and inclinations would lead them to breadths as well as depths of knowledge and for whom the ordinary requirements of the curriculum were more hindrance than help in the fullest realization of their own potentialities and those of the liberal education.

For such men, Mr. Hopkins reflected, the ideal program would be one in which, toward the end of their college career, they might be given the freedom to develop through self-directed study without restriction, regulation, or requirement.

When in November, 1928, he received a letter from Raymond Pearl '99, director of the Johns Hopkins Institute of Biological Research, Mr. Hopkins knew at once that he had at last found the means of implementing his wishes.

Dr. Pearl was writing to ask the President's reaction to a plan of Senior Fellowships which he as a trustee had proposed and which only a month before had been instituted at St. John's College. He enclose a printed description of the program.

The President was, to say the least, enthusiastic and declared in reply, "If I can find any willingness in our faculty committee on educational policy ... I should like to steal your idea, and I should like to start in on the basis of experimentation along the plan you have outlined."

Both men considered it a righteous theft. (One well-wisher later commented that the idea was so good, "I wouldn't care from what place it had been burglarized—St. John's College or the Kingdom of Heaven.")

The willingness of the Committee on Educational Policy was readily demonstrated by their approval of the plan without a dissenting vote, and on April 2, 1929, there were established by vote, of the Trustees the "Senior Fellowships of Dartmouth College" under a plan very similar to that of St. John's.

The resolution cited as the purposes of the fellowships: "that added stimulus may be given to the genuine spirit of scholarly attainment in undergraduate life and that the cultural motives of the liberal arts college may be emphasized; and in order that the tendencies of the honors courses toward freedom from routine requirements may be carried to further development in the cases of men outstandingly competent to utilize such freedoms; and further that illustration may be given in the undergraduate body that the acquisition of learning is made possible largely by individual search and in but minor degree by institutional coercion."

Each year the President, after conferring with members of the faculty and particularly with a special committee representing both faculty and administration, was to nominate to the Trustees five men from the junior class to be Senior Fellows during the following year.

The only requirement of the Fellows was that they be in residence and good standing at the College throughout the year of their appointment. They were to have "complete freedom to pursue the intellectual life at Dartmouth College in whatever manner and direction" they themselves might choose. They need not attend classes, take examinations, or pay tuition fees. At the end of the year they would receive their degree in course.

With the anouncement by President Hopkins on June 11, 1929, of the appointment of five members of the Class of 1930 to be Senior Fellows during the next academic year, the experiment was under way.

In the thirteen years that followed until the war caused a suspension of the awards, 87 men were elected Fellows. During this period the program was the object of high praise, of criticism, and of denunciation.

The majority of the faculty appears to have been from the beginning either to some degree critical of the plan or definitely opposed to it. Many believed that the complete freedom of the fellowships should be modified, that certain conditions and general requirements should be introduced, a nd that some of the methods of administration should be changed. And eventually, in deference to faculty feeling, various refinements were made, such as requiring that candidates outline a project that they wished to pursue, that advisers should be assigned to the Fellows, and ultimately that the free tuition provision should be eliminated.

The undergraduate body seems generally to have strongly supported the plan. Although there were, to be sure, tongue-in- cheek remarks about bowling or poker games in the Paul Room (the Fellows' headquarters in the library), and somewhere along the way a new verse about the Senior Fellows was added to "Where, Oh, Where?" containing the line "They've gone out from a year of loafing."

(It might be reflected that if undergraduate facetiousness were considered always tantamount to well-deserved condemnation it is doubtful that there would be a valid idea, a virtuous person, or a thing of worth in all of creation.)

The Dartmouth through the years consistently championed the fellowships, holding that "in the Senior Fellowships, Dartmouth's educational tradition has its finest expression." Editors frequently expressed the belief that the authorized number of recipients should be increased.

The United States entered the war in December, 1941, and it was decided that after the Fellows from the Class of 1943 had been designated a few months later, no further appointments would be made until the war was over and the College had returned to normal operation.

When in the fall of 1946 it appeared that this condition was now on its way to realization, it was decided that before taking any action on re-instituting the fellowships a thorough and long-range study should be made. A five-man faculty committee was formed to determine the desirability of re-establishment and, in case such proved desirable, to outline the manner in which the fellowships should operate.

The committee devoted two and a half years to a meticulous investigation into the voluminous files accumulated on the fellowships since 1928. Also, letters of appraisal and comment on the program were solicited from former holders of the fellowships and from members of the faculty.

The response of the former Senior Fellows was heartening both in number of replies and in the helpful and interested spirit which characterized their detailed and candid letters.

The experience of these men under the fellowships was varied, as is attested by their own remarks: "the most rewarding year I ever spent," "I do not believe either the College or myself profited greatly," "afforded to me what I regard as the most valuable experience of my life," "I think it was a wasted year," "one of great formative importance to me."

The committee reported that of the 64 replies received, all but three supported the program as valuable and favored its continuation. Even of the few men who considered their fellowship a failure, most felt that they had "thrown away the advantages which the fellowship had to offer" and that "the inherent idea of the fellowships ... is excellent."

The letters treated all aspects of the program from basic philosophy and purpose to particulars of administration. There was comment on the place of extracurricular activities, the number of Fellows, the areas of study, the idea of accountability, the desirability of a required project, and many other particulars.

But the two matters to which the former Senior Fellows devoted most attention were the questions of supervision and selection. Opinion was as diverse, and in some cases as opposite, on this point as on any of the others.

There were those who believed that any supervision was a contradiction of the very purposes of the fellowships and considerably diminished the value of the program. Others advocated that "each fellow be required to consult with a member of the faculty once a week" and that there was a need for "a certain amount of discipline, regardless of the mental caliber of the individuals concerned."

Most men took the position that "supervision is not exactly what is needed. Counsel and advice, on the other hand, are required. " The experience of freedom and self-direction, they felt, was not lessened by having a capable and sympathetic person to whom one might go for help. But it was made clear that advisers should advise, not direct, nor should they conduct "a oneman seminar."

It was selection with which nearly every- one was greatly concerned. Various devices, means, and criteria were suggested as aids in choosing the Fellows, but it was generally conceded that there really were no infallible standards. The consensus was, however, that upon selection "depends the success of the Senior Fellowships," and, as one man put it, "successful selection depends very largely on the caliber and so- phistication (in the best sense) of the men who do the selecting."

Faculty response to the appeal of the committee was less gratifying than was that of the former Senior Fellows, but of those who did respond, over 60 per cent supported the program with reservations and criticisms much the same as those expressed by the other group.

With this information at hand, the investigating committee prepared its report. It recommended that the fellowships be reestablished, but that they be governed by a new set of policies.

The program was to be administered by a standing committee of the faculty, among the duties of which was the selection each year of not more than ten qualified men from the junior class to be Fellows the following year. Candidates might apply directly or be nominated by undergraduates, members of the faculty, or administrative officers. Each Fellow was to work under a faculty adviser chosen by him with the aid of the committee. Fellows might be relieved of all courses except Great Issues, and they were not required to take comprehensive examinations.

These proposals were endorsed by the faculty through the Council in May, 1949, and recommended to the Trustees for consideration. Following approval of the plan by the Board, preparations were made to set the machinery of the program into motion.

In the spring of 1950, the first postwar Fellows were chosen from the Class of 1951. Of this group of ten, some were men of high academic standing, while others were only slightly above average with respect to grades. Some had participated to a relatively great extent in extra-curricular fields, others in relatively small measure. Their interests, activities, and intentions were quite different.

But they were alike in that each had been selected as one capable of profitable independent study; each had a purpose the highest fulfillment of which lay beyond the structure of the regular curriculum; and each had now been given the opportunity, unimpeded by course requirements, to undertake during his senior year a project which might lead to the accomplishment of this purpose.

The Senior Fellows from the Class of 1951 are now nearing the end of their term and the first cycle under the postwar program is approaching completion. It once again becomes a pertinent question to ask: "Where, oh, where are the Senior Fellows?"

For the ten men of '51 it is probably a question with no immediate answer. Each of them will report on the business of his fellowship. But with regard to the real value of the experience it would seem too soon to tell; the testing-time lies in the future.

Concerning the program itself there is perhaps better chance to make valid judgment on where it is, or more precisely, where it's going.

The future would seem to depend chiefly on two factors: selection of the Fellows and the Fellows themselves.

There are no hallmarks by which to know the student possessing the capacity, initiative, self-reliance, and other qualities requisite to making the most fruitful use of these fellowships. It needs no re-explanation that the most brilliant student is not necessarily the student best suited to benefit from the program, nor is the program designed to meet best the purposes of every student.

The committee selecting the Senior Fellows must guard against mistakes in the difficult business of selection not so much for the sake of the program as for the sake of the student. The program would suffer but little from the appointment of one or two poorly qualified men, but the individual might lose greatly.

The Senior Fellows, for their part, in receiving these awards should recognize in the honor they convey, the responsibility implicit in that honor. There must be realization that a Senior Fellowship is primarily a responsibility and an opportunity for a purposeful man.

The program's success in becoming increasingly important and valuable to the student and to Dartmouth will be assured through the judicious selection of Fellows who are both cognizant of their responsibility to the College and themselves, and equipped and anxious to make the most of an educational opportunity that is unlimited.

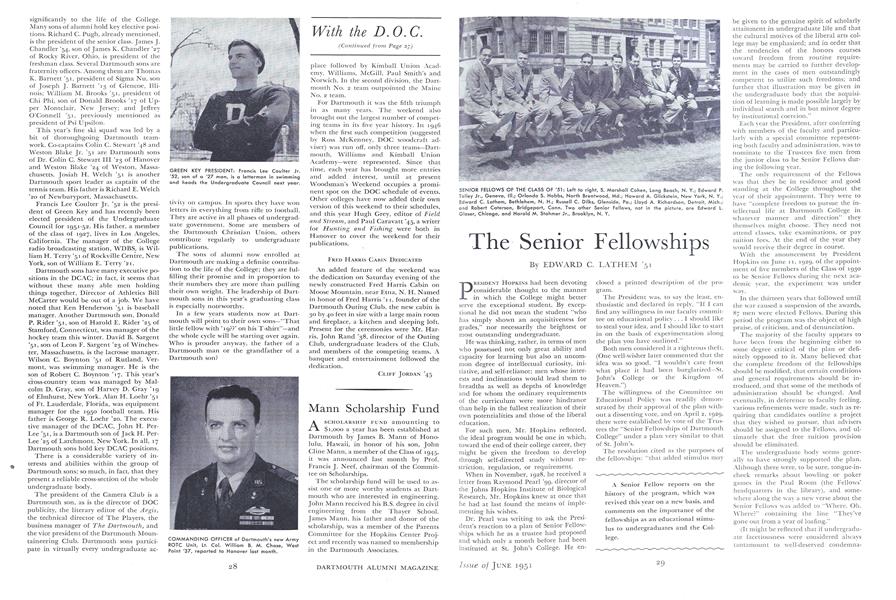

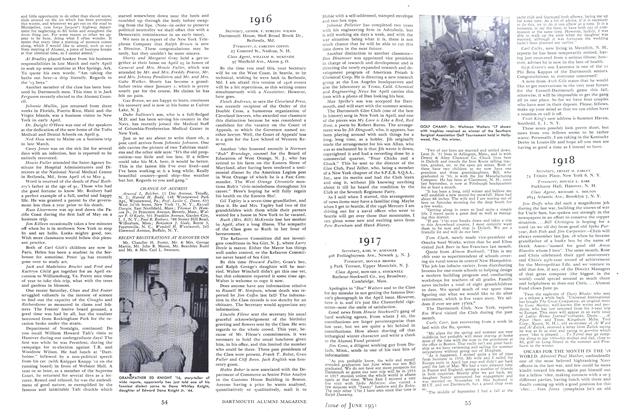

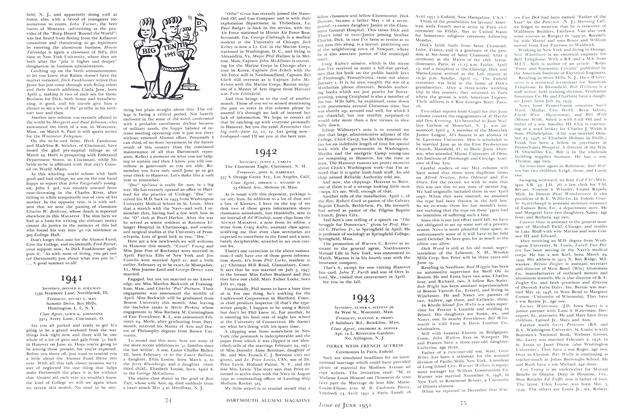

SENIOR FELLOWS OF THE CLASS OF '51: Left to right, S. Marshall Cohen, Long Beach, N. Y.; Edward P. Tolley Jr., Geneva, III.; Orlando S. Hobbs, North Brentwood, Md.; Howard A. Glickstein, New York, N. Y.; Edward C. Lathem, Bethlehem, N. H.; Russell C. Dilks, Glenside, Pa.; Lloyd A. Richardson, Detroit, Mich.; and Robert Caterson, Bridgeport, Conn. Two other Senior Fellows, not in the picture, are Edward L. Glaser, Chicago, and Harold M. Stahmer Jr., Brooklyn, N. Y.

50-YEAR SPEAKER: The Rev. Robert F. Leavens '01 of Berkeley, Calif., who will give the traditional 50-Year Address on behalf of his class at the Alumni Luncheon on Saturday, June 16.

CARLETON BLUNT '26, president of the General Association of Alumni, will conduct the annual luncheon meeting of alumni, faculty, seniors and their fathers in the gym Commencement weekend.

A Senior Fellow reports on the history of the program, which was revived this year on a new basis, and comments on the importance of the fellowships as an educational stimulus to undergraduates and the College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

June 1951 By ROBERT H. ZEISER, DAVID S. VOGELS JR., JOHN F. STOCKWELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARS, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

June 1951 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

June 1951 By ELMER T. BROWNE, DONALD G. RAINIE, FREDERICK L. PORTER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

June 1951 By ELMER G. STEVENS JR., STANTON B. PRIDDY, THEODORE R. HOPPER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1904

June 1951 By DAVID S. AUSTIN II, THOMAS W. STREETER, CHARLES I. LAMPEE

EDWARD C. LATHEM '51

Article

-

Article

Article200th Anniversary Development Program

May 1958 -

Article

ArticleDisaster

FEBRUARY 1968 -

Article

ArticleEnrollment

November 1968 -

Article

ArticleEnvironmental Impact

SEPTEMBER 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Article

Article1944

May 1951 By ROBERT A. MILLER, A. KINGMAN PRATT, L. DONALD PFEIFLE -

Article

ArticleSwitzerland

December 1976 By RONALD T. MURPHY