The Class of 1951 Valedictory to the College

THIS is one of the moments men of Dartmouth can never forget. This scene, with its magnificent panorama of color and its. fascinating mixture of varied emotions, is one which shall live always in our memories as the symbolic link between "the splendour and the fullness" of the last four years and the uncertainty and the challenge of the years to come.

Seldom have Dartmouth's sons faced' a more crucial future, a future more filled with a paradoxical blend of great opportunity and ominous peril.

America's opportunity today is without parallel in history. The richest, most powerful nation on earth, America possesses the potential necessary to lead the world to a new era of prosperity and order, based on freedom and justice. The free world looks to us. It is we who must lead.

Our unprecedented opportunity, however, lies in the shadow of an unprecedented threat to the deepest roots of our democratic way of life, a threat both external and internal.

The more obvious threat is from without, in the form of amoral world communism, which animates and, in turn, is borne by Soviet imperialism. The more fundamental and insidious threat to our way of life is from within.

Back in 1776, our Founding Fathers committed us, as a nation, to a definite set of first principles, a definite set of human values.

Our nation was predicated on the propositions that all men are born free and equal; that man, endowed by God with mind and spirit, possesses a great capacity for material, intellectual, and moral achievement; that government exists only to enable man to utilize his capabilities to the fullest measure; and that for the good of all, man must be guided by good will and justice in his dealings with other men. These are the principles from which democracy derives its strength. Guided by them, America grew vibrant and great.

But in our fabulous rise to prosperity and power, we became so deeply engrossed in our material well-being that we tended to lose touch with the spiritual mainsprings in which our progress was rooted. The spiritualism which made the American Soul great was gradually purged with materialism. We slowly lost our dynamic faith in our liberal way of life. As we grasped for material things, we let slip through our fingers the deep spiritual and moral consciousness which moved Lincoln to write of the Declaration of Independence that it gave "liberty not alone to the people of this country, but hope for the world for all future time."

Today, the evidences of our tragic loss of conviction are seen throughout our society. Before the internal and external threat posed by communism, we, no longer strong in our faith, have become confused, afraid, and even hysterical. In our feverish preoccupation with security, we have shown a dangerous tendency to undermine the very way of life we would protect. Having forgotten that our historic security has been the by-product of freedom buttressed by a steadfast faith and tireless effort, we are attempting in various aspects of our lives today to gain security by limiting the very freedom we would safeguard.

It is the great hope of the future that the American people can once again, as so often in our proud past, rise to the challenge to our way of life with a reaffirmation of the fundamental values of liberal democracy which have made us what we are. Only by returning to these first principles can we hope to realize our magnificent potential and prevail over the peril which would destroy us. The heritage of Western Civilization, which is rooted in the noblest thoughts and deeds of twentyfive centuries, hangs in a very real way upon our resolution, our faith, and our endeavor.

If we are to avoid the fate of so many great civilizations in history which have lost their moral fiber, we must renew our faith in the liberal democratic idea as the means to a richer, fuller life for all men, and we must live out this renewed faith in our daily lives. Only by living out our be liefs can our idea become contagious, as it must, in the world of the mid-twentieth century.

The task of rebuilding our nation's spiritual strength rests not upon the few who may lead us, but upon each and every one of us, no matter what our calling in life may be. What our democracy can do will be determined not by what a few of us say, but by what we, as a people, believe and do. The responsibility of this generation is an awesome one. But we dare not default.

Dartmouth has done much to build in us the strength of body, mind, and spirit so indispensable if we are to assume the responsibility of our times. We have gained here an appreciation for the liberal tradition of our democracy. This appreciation has derived not only from our intellectual adventures in the liberal arts but more fundamentally from our daily lives in the Dartmouth community. We have learned to understand democracy; we have learned to live democracy.

Four years ago we gathered on the Hanover Plain literally from round the girdled earth. The first significant characteristic of the Class of 1951 was our diversity and our individuality, and before long we began to respect this diversity and this individuality. We learned to respect others with different backgrounds, different viewpoints, and different capacities. We came to realize that a man's ability to produce depends not on his race, creed, or social status, but rather on his character, his effort, and his insight.

Gradually out of our diversity grew unity. As Dartmouth undergraduates, we became increasingly drawn together by a loyalty to the College and, more important, by a growing community of conviction in a common set of values. Without sacrificing for a moment our precious individuality, we have been bound together by a common respect for the intrinsic worth of the individual, the importance of a free search for truth, and the compelling need for morality in man's dealings with his fellow men. But these are more than the values of Dartmouth College. They are the values of free men of vigorous mind and spirit everywhere for all time. And the unity we have found in these values at Dartmouth is the same unity which we need so desperately today to fashion out of the diversity in American society.

Above all else, America needs now a rebirth of the community of conviction which has inspired such remarkable examples of common effort in our past. We must meet the realities of the present, so full of potential disaster, with balanced judgment and moral responsibility, inspired by a revived faith in our fundamental values. In this way we will be able to show the world that we have more than A-bombs and industry to offer mankind. We will be able to show the world, as we must, that liberal democracy, not totali- tarianism, is the path to the good life for all men.

Dartmouth has planted in us the seeds of the moral and intellectual leadership America so critically needs in all walks of our society. We have gained a deep feeling for the ideas of liberal democracy.

If, however, these ideas are to be more than pathetically impotent dreams, they must live in the minds and deeds of brave and good men. It is we, fellow men of Dartmouth, who must be these brave and good men.

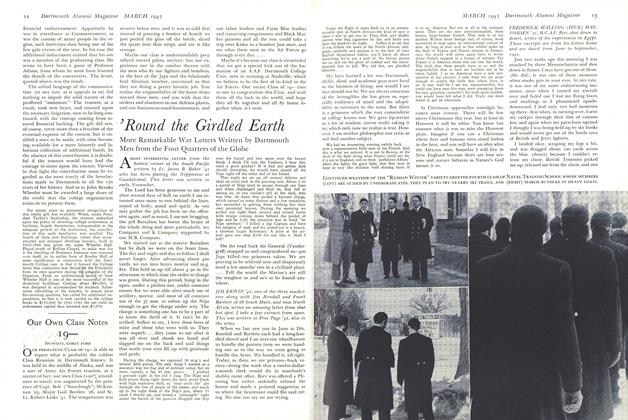

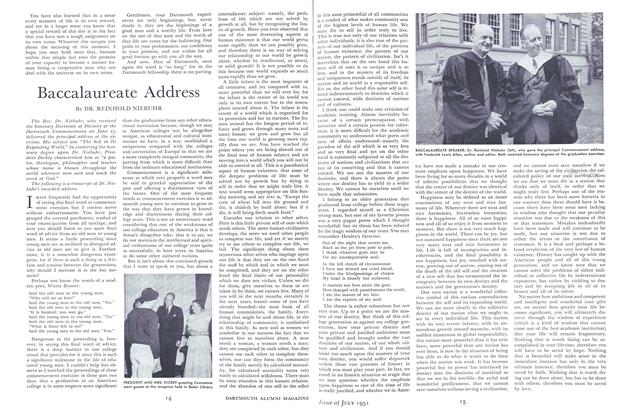

VALEDICTORIAN: Richard C. Pugh '5l of Phila- delphia, who delivered the farewell to the College for his class, shown conversing with Dean Neid- linger before the start of the Class Day program.

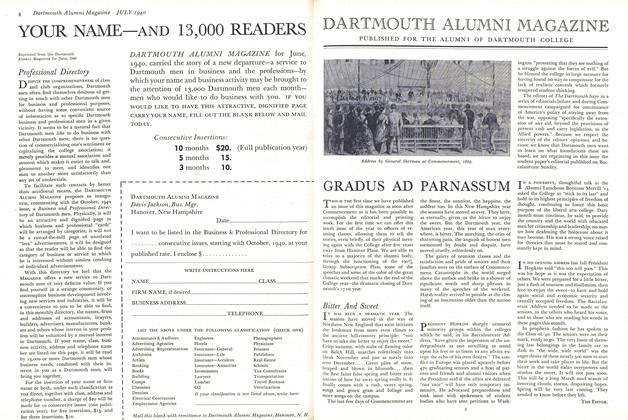

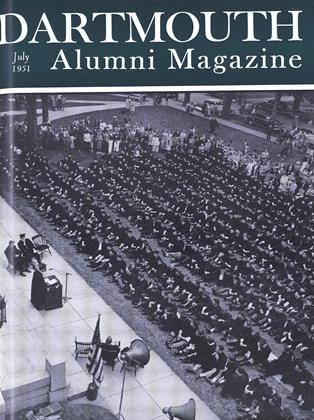

COMMENCEMENT MORNING: Seated in front of Parkhurst Hall, awaiting the start of the academic procession to the Bema, are (I to r) President Dickey, President Emeritus Hopkins, Trustee John R. McLane 'O7, Arthur Hays Sulzberger, who received an honorary LL.D., and Governor Sherman Adams '2O of New Hampshire. Dean Neidlinger, head marshal, is standing at the left. Others seated are Trustees, honorary degree guests, and Deans of the College and associated schools.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1921 Has A Lively 30th

July 1951 By REGINALD B. MINER '21 -

Article

ArticleThe 1951 Commencement

July 1951 By C.E.W -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911 Has a Memorable 40th

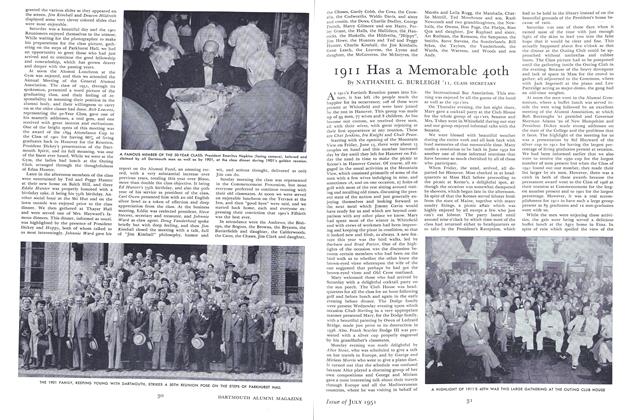

July 1951 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH '11 -

Article

ArticleBaccalaureate Address

July 1951 By DR. REINHOLD NIEBUHR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926 Holds "Terrific 25th"

July 1951 By PAUL VENNEMAN '26 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941 Weathers Its Big 10th

July 1951 By FRANK M. HALL '41