MY distinguished predecessor on this platform, Governor Adams, opened a new section of your course called American Issues and Democratic Values. To judge from the topics listed in the course schedule, you are to discuss various issues that arise because of the kind of people we are and the way we do things, and the possibilities that these problems can be solved in ways acceptable to the American people.

Now, what has Science got to do with these things? Everybody knows that a scientist is an escapist. He tends his little patch of cabbages in an utterly unreal world of abstract things. If he chooses to deal with a problem, once he knows the facts they are the answer. It is my understanding that in this course you consider problems which every man has forced upon him whether he chooses or not, and whose answers are generally either physically impossible, or politically impossible, or repulsive. What indeed has Science to do with public affairs, with the American scene, with Democracy?

There are two sides to Science. To make it worse, each of the sides has two sides, but I shall try to leave you somewhere this side of the fourth dimension.

The two sides to Science are the drive to know, and the drive to use that knowledge for purposeful actions. One distinguishes between pure science and applied science, or Technology. Let us consider Technology first.

Science, as translated into technology, is the mother and the father and the grandmother of all the most vexing problems of modern society. I can make the point rather briefly because I assume that this opinion is amply developed in about twothirds of the courses in the curriculum, that is, outside of the Science Division. You are undoubtedly familiar with it.

There are two sides to Technology. As a result of the application of scientific discoveries in ever increasing degree to the development of Western civilization, life is better—and life is worse. It's easy to say that life is better because we know how wealthy we are now in comparison with the old days. We know what we have in the way of things. How long would it take you to list all the purchased things belonging to yourself and your family? We know what we have in the way of mechanical power. In 1800 there was available in this country about a twelfth of a horsepower per person. By 1900, through the development of technologies, there was about a fifth of a horsepower per person—which more than doubled the amount of work that your grandfather didn't have to do himself. And by now there is approximately ten horsepower per person, which is a fifty-fold multiplication in the last fifty years. The end is nowhere near in sight.

Wealth in things and power is translated into all kinds of improvements in health, in security and in leisure. The expectancy of life of people like you and me here in Hanover in 1800 was about 21 years. Ours now is up toward seventy years, which is really a remarkable thing. In addition to the mere life expectancy, we have less sickness and less incapacitation, disability, crippling, and so forth per year than those fellows did. It is of some advantage to be able to stick around for all five acts and see life through in all its richness. The chance to try it is a triumph of technology.

We are reasonably secure from natural dangers, like cold, starvation, wild beasts, preventable diseases and parasites. And at least we are trying to make ourselves progressively freer from the dangers that Man creates/That is a much more difficult job because Man is much more ingenious than Nature in devising trouble for himself.

We have a superabundance of leisure now in comparision with pre-technological people. Leisure can be used for pleasure, which is nice, but not particularly important. What is more important is that we have leisure for self-realization, which is, many of us think, the only really satisfactory thing.

I'll bet there isn't a person in this room who knows the anthem Amesbury, which was sung once a year at the college chapel for a solid 150 years. Only since the last war has the traditional singing of Amesbury dropped out at Dartmouth College. It may be that not even any member of the Glee Club knows the verse that goes: Oh that each in the day Of His coming may say "I have fought my way through; I have finished the work Thou didst give me to do."

There's a priceless satisfaction that comes from having done the job that seemed the best for you to do, and done it well. You can stand back and look at it and know it could have been worse. Technology increases the opportunity for a person to have that rich reward from life.

But there is a second side to Technology. Science has also made life immeasurably worse. There is the Malthusian trap, for instance. In this country we can be blissfully unaware of the existence of the Malthusian trap. But there are countries in the world where you can increase production without getting any place. None of these advantages that we have gotten through technology come through. What happens is that the increased production is outstripped by increased population, so what you end up with is not an increased standard of living. This trap has sprung, as you perhaps know, in a good many parts of the world. It was through policies conceived in this country that it has sprung on the Puerto Ricans. It has sprung in Japan and Egypt and various parts of India and so on. The facts are available and clear. It is not yet known whether the trap can be unlocked.

There is no such thing happening to us in this country. On the other hand, with all the advantages that applied science brought us, we also got the tremendous social and economic and political turmoil that comes from fast technological change. When rayon and nylon displace cotton and silk, people are thrown out of work; people have to change from one place to another; there's insecurity, and worry and waste. The busses are putting the trains and the trolleys out of business. The big corporation farm with the heavy machinery is swallowing up the little family farm. Television is putting radio and the movies and—who knows?—perhaps grade-school education out of business. Technology is continually bringing up new things to jolt the economy and keep society in a turmoil.

And with the increased integration of big industry and big commerce, there necessarily comes centralization, and the standardization and regimentation of people. One gets to be a cog in a machine so enormous that one doesn't even know its dimensions. One of the great advantages of the American way of life, the chance to start up one's own business, is rapidly disappearing because the initial investment now has to be so big. The integrated economy has become so delicately poised that one man in the port of New York, for instance, can discommode all of the people in the United States. It is possible for a huge industry to be crippled and for people to be thrown out of work all over the country by the decision of half a dozen people. The economy, as you know, goes through periods of extreme stress just because it is so intricately tied together and so sensitively built. Democracy of the New England town meeting type cannot handle the centralization of control that is necessary when the economy gets the full treatment from Technology.

And what is the human value of technological civilization? Compare the faces of people scurrying through Penn Station with the faces of people who are not living in an industrial economy. Measure our divorce rate, our suicide rate, our rate of mental breakdown. In these respects, the American civilization has lost ground. Talk to visitors from other parts of the world. One of the most interesting lectures that I have heard in the five years that this course has been running was by Charles Malik, the representative of the United Nations from Lebanon. (I mean the Lebanon at the other end of the Mediterranean.) He comes from quite another kind of society. Contemplating our way of life, there were some aspects that he admired and some that he definitely didn't. In general visitors from abroad are polite. They show a marvelously controlled rapture, an incredibly well concealed enthusiasm for these complicated and distressing aspects of our civilization. We are not always quite sure, to look at them, that they are really envious of us.

I spent a bit of time this summer with a Navajo family far enough out in the middle of the reservation so that they were relatively untouched by all this business. They had no furniture and no boughten machinery. The culture that they had was obviously rich and there was a good deal of beauty in it, though utterly different from ours. They wouldn't have swapped for anything. They knew about radios and the movies and that sort of thing. They stuck there in the midst of that fearsome desert and made the best of it because, to them, their life was more satisfactory than ours. These things are very striking when you meet them. There's something to it.

As you go on with your broad survey of the kinds of problems that are arising in this technological civilization of ours, you may very well come to the conclusion that I have come to, that our society is continually producing bigger and bigger problems, and all we can do with any one of these problems is to extemporize in ways that create six other problems. The longer we go on with this business of developing a technological civilization, the more difficult it is to understand what's going on and keep it under control. So, by the application of technology, life is made better, but it is also made worse.

I think the epitome of this sort of thing was contained in a remark that Senator McMahon made a short while ago. He is on the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy and was discussing various defense proposals that were coming up before Congress. He said, "At the rate we're moving I can see ahead only two ultimate destinations: military safety at the price of economic disaster or economic safety at the price of military disaster." And he went on to plead for—guess what—an atomic army and an atomic navy and an atomic airforce, which many of us consider as the complete perfect formula for ultimate complete perfect disaster. Obviously, there's some high level extemporizing going on, and he certainly has no illusions about the problems that are being raised by our solutions to the problems that are right in front of us.

Professor Wolfenden, who has talked in other semesters in this course about the dilemmas that this overdose of technology has got us into, disposed of all the neat solutions to the situation—including the one about a moratorium on science where we put all the engineers into the ice-box— and he said there isn't any way out but only a way on. If I may vulgarize his expression of that way on, it's simply this: hold onto your hats, boys, it's going to be a wild ride but let's do the best we can.

You can't outlaw scientific and technological advance. To do that would be to deny the right—or the duty, for that matter—of the human mind to express itself. You can't suppress curiosity and inventiveness any more than you can suppress the sexual drives. It is by virtue of the fact that we are human beings rather than frogs or fishes that all of these things do keep us in trouble. It's part of the great human adventure to make the best of them.

Now, for a few minutes I'd like to turn from Technology to Science in the stricter sense of the drive to know, and relate this to democratic American society. You may find my logic from here on is a rather delicate fabric unless you listen carefully to a couple of definitions. I want to define Science and Democracy in my own way and then make a relation between them in what I shall consider to be a secular way of life.

Science isn't any particular body of knowledge but a way of expanding and modifying knowledge. You'll notice I'm not talking about Technology or applied science, now—l'm talking about the search for understanding. In Science there aren't any sacred books or any high priests. If you're a new one in the business and make an observation that you think is true you have the privilege of saying it; and you may be an upstart, but you may contradict the expert and replace him. In Science the individual's mind is liberated for his own inquiries into the nature of things and there are no frontiers and no guards and no fences. The human mind has free access to the facts.

Now Democracy has elements in it that are surprisingly similar. Democracy isn't any particular way of life. It's a collection of devices for allowing changes to be brought about in ways of life by individual action or group action. It's a mechanism for keeping things moving. Individual powers of action in Democracy are liberated from restraints of class or creed. (You understand that I am talking about the ideal democracy. We don't have either ideal Science or ideal Democracy; I'm declaiming what they should theoretically be.)

In a democracy different ways of life are permitted to co-exist and to compete with each other peaceably. Under Democracy there is not only a liberation of human action but an encouragement, a fostering of new outlets for human genius. As Mr. Canham said to you, it is a revolutionary device whose function is to remove the necessity for periodic violent revolution by encouraging peaceful change. In a democracy you can become the boss of your boss, you can fire the bureaucrat or the ruler without shaking society to its foundations. The human spirit in Democracy is free to extemporize and remodel the pattern of life through due process and peaceful action.

Now let's put these things together. Science and Democracy together complete the liberating process that was started in the Protestant Reformation. Science deals with the realm of the mind and Democracy deals with the realm of action. And I am submitting to you that the two, Science and Democracy, are the basic elements in American culture.

Now, if I define a society which is based on Science and based on Democracy as a secular society—which is a perfectly defen. sible use of the word—we can go on and make note of what is perfectly obvious: that our society has been powerfully molded by secular forces: by scientific thought and democratic action. The sound of that word interrupts me. By molded, I mean shaped or guided, not mildewed. Somebody is likely to come at me with that when I've finished if I don't make it dear.

Horace Kallen of the New School for Social Research, writing recently in the Saturday Review of Literature, carries this point about the scientific-democratic nature of American society a bit farther. He calls it the American religion.

What is a religion, now? Each one of us has his own religion. It is something that one is devoted to. It is a body of belief which governs one's choice of actions. Secularism, says Kallen, is a wholehearted belief in and a dedication to Science and Democracy. It holds fast to that which it sees to be good. Not to the facts of today, because we know that the facts of science change from time to time as we keep improving our knowledge. We hold fast to the way in which the facts of today are replaced in favor of better facts tomorrow. We hold fast to the mental freedom which is the prerequisite for the scientific process. And this secular religion also holds fast, not to the concrete expression of Man's social or political or economic drives today—institutions, patterns of action and so on—but the methods by which each of us can remodel them toward a more satisfactory tomorrow. We really believe that Science and Democracy can offer these advantages.

All right, if this is a creed and a devotion, it is a religion. We defend Science and Democracy in this country when necessary with the fierceness of a religious devotion and with an invincible faith in that secular religion. You can see the elements of truth in this. If you are a skilled logician you can also see how you can set the whole thing aside by redefinition. But there's a point in here that's worth considering.

Communism is also spoken of nowaday as a religion. It is a creed which is accepted on faith and it is a devotion to a way of life. Most of the religions that have names are connected with churches and hierarchies, and so forth, and are of a more exclusively spiritual nature. The secular religion that Kallen finds to be characteristic of our society and the Communistic religion that is preached in Stalinist circles are both secular religions, but of utterly different types. One is a religion of freedom and the other of repression of freedom in the counter-revolutionary sense that Mr. Canham spoke to you about.

One cannot compromise much in religious matters. A man cannot have a fierce devotion and a faith without being convinced that it is the best and only true one. A proponent of Democracy and Science, as the words are understood in this country, cannot compromise on any fundamental principles with a Stalinist—and vice versa. Last year the Catholic Bishops issued a strong statement against secularism in America. There are secular men among us who fear Catholicism, and there are Protestants who fear both secularism and Catholicism, however easily we can demonstrate to each other that we can all be neighbors and allies in worldly matters. Irreconcilable differences in opinion are bound to exist between any two men of different religion, since the basis of a faith is something that you know you have got to accept whether it can be proved objectively or not. After you have got it, the belief can be put into as logical a framework as you please, but the framework always rests on assumptions that have to be taken or rejected as an act of faith. The logic is not very important. The Devil is the best logician of them all. and he is not sent tumbling by logic.

Yet to a unique degree, this "secular religion" which characterizes American society is a tolerant religion. One of its ideals, both in the realm of Science or thought and in the realm of Democracy or action, is that the human spirit should be allowed to express itself in its own way and its own time. The feeling in Science is that it should be possible for anybody to study anything, and to formulate conclusions and advertise those conclusions. While this is bound to produce unreliable as well as reliable information, if there is a free market of ideas people will teach each other to shop wisely. In Democracy, it should be possible for anyone, however crazy, however interestingly different, however unique—and all of us are unique to a degree—to work out his own pattern of living as long as he doesn't get in the way of other people too much. This tolerance overflows in the relation of Science and Democracy to the other religions also. Since there is no agreement that any one theology or any one ethics or esthetics is the best for all of us, a man should be able to pick and choose or create for himself.

Some of the thorniest issues that you will hear discussed this year arise out of the paradoxes of tolerance. You can't be tolerant in this world without being intolerant of intolerance. That's the one that drives the pacifists to war. And you can't allow the full privileges of the free market to the people who are hell-bent for destroying the free market.

And a point which Kallen hasn't mentioned is that most of us who have inherited this secular faith and devotion to Science and Democracy have also inherited a religion identified with a particular church and creed. Therefore there exists potentially within each one of us a conflict of religions. I think that's why most honest men find themselves divided within their hearts on issues which bring their church religion and their secular religion into conflict. The only fellows who have the sure, ready answer to the church and state issues that come at us in so many forms nowadays are the ones who are not divided in their hearts; who are devoted to only one religion. The secular way of life we follow is a peculiarly difficult one.

To come back now to American Issuesand Democratic Values, I have attempted to point out that some of the inescapable problems you will be discussing are an outgrowth of the technological triumphs of Science and that these issues will need to be handled by methods acceptable to a secular society, a society devoted to both Science and Democracy. You may come to the conclusion that the development of technology was a tragic fraud—there are indeed two sides to the question—but you have got it to live with and it will outlast you. The very ancient arguments as to whether the secular pursuit of scientific knowledge and the flux of living patterns that you get in a democracy are good or bad have been revived again since you were born and have never flamed higher than now. The counter-revolutions against the secular revolution are in the interest of forcing people into a mold, making them go to particular schools, learn particular creeds, serve this person or that institution, do this, do that, and it is a rather easy thing to pinpoint the difference between the tolerant secular attitude and the intolerant party or sect-line pattern of thought, by raising the question, how shall we seek the answer to this problem? The scientist and the man for democracy take the non-violent way, the hard way, the way in which all the factors and all the people are considered.

That is the spirit in which American issues are being tackled today. I say this in faith and pride and a small degree of hope. The counter-revolutionary tide has never run so strong against us. The men in this room, properly placed, could throw the balance for our lifetime.

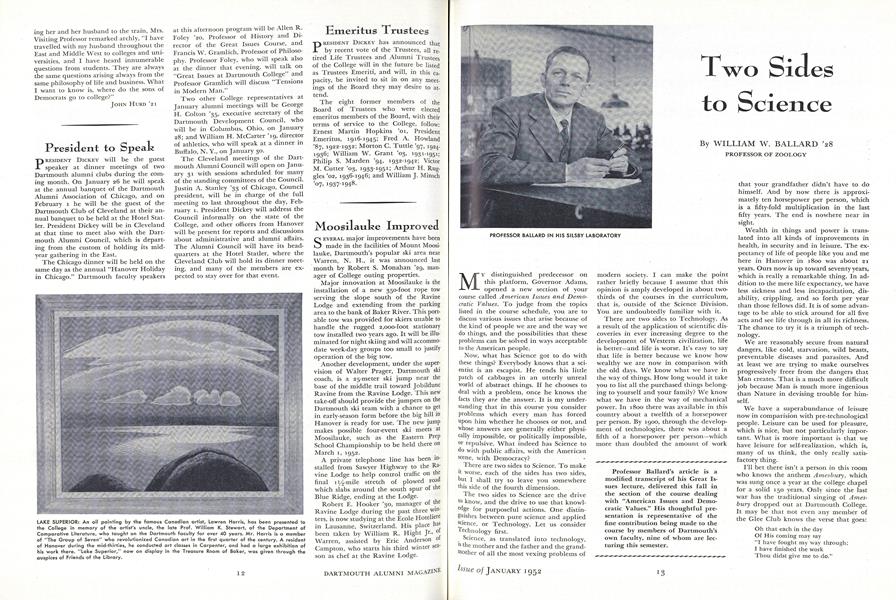

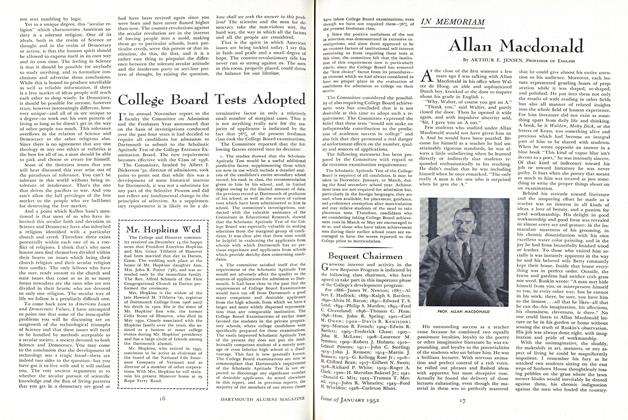

PROFESSOR BALLARD IN HIS SILSBY LABORATORY

GREAT ISSUES SPEAKER: Crawford H. Greenewalt (center), president of the duPont deNemours Co., is shown in the Public Affairs Laboratory after his lecture on "Individual Incentive and National Development." With him are (I to r): John W. Pegg '52 of Scarsdale, N. Y.; Prof. Allen Foley '20, director of Great Issues; and Richard M. Watt '52 of Glen Ridge, N. J.

Professor Ballard's article is amodified transcript of his Great Issues lecture, delivered this fall inthe section of the course dealingwith "American Issues and Democratic Values." His thoughtful presentation is representative of thefine contribution being made to thecourse by members of Dartmouth'sown faculty, nine of whom are lecturing this semester.

PROFESSOR OF ZOOLOGY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

January 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

January 1952 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

January 1952 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, JACK D. GUNTHER -

Article

ArticleConcerning the Princeton Game

January 1952 By C.E.W. -

Article

ArticleAllan Macdonald

January 1952 By ARTHUR E. JENSEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

January 1952 By JOHN J. FOLEY, JOHN E. GILBERT, JAMES F. WENDELL

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE SHEEP'S HEAD IN THE TROPHY ROOM

February, 1914 -

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL COACHES SECURED

April, 1915 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH MEN ELECTED TO GOVERN TWO STATES

December 1920 -

Article

ArticleDegrees Awarded

December 1938 -

Article

ArticleThree Dorms Closed

January 1943 -

Article

ArticleWarm Memories, Cold Pleasures

February 1976 By DAN NELSON '75