DEAR ANDREW: Shall young Andy, who is coming to college this fall, apply for admission to one of the ROTC units? Your question is a poser; all I can do is to put the pros and cons before you and him.

You tell me that he will be eighteen the last of August this will make him, incidentally, about the age of the average freshman. That means that he will be registering for Che draft just before he comes to college and will not be subject to induction until the last of February. He will be sure then of one year of college, for even if he were called up in the spring as now seems unlikely he would be entitled to the statutory deferment which would allow him to finish his college year. As I understand it, the draft boards over the country are not yet working in the nineteen-year-old group; but, with men who have served their two years now being discharged, and with the likelihood of increased draft quotas to keep the armed services up to their present strength, it is not improbable that he might be called during the next summer.

If, however, Selective Service continues its present policy of deferring students on the basis of a qualification test and their class standing, he might reasonably expect another year of college. (This is assuming that he is as bright as his father - from what you tell me, he is even brighter!) What would happen to him at the end of two years of college is so far ahead of us that perhaps we had better not speculate beyond that. To sum up his situation vis avis the draft: he is sure of one year of college and may get a second year this is a gamble, but not a rash gamble. (All this discussion, of course, is predicated on the continuance of the present world situation; on this point your judgment is as good as mine.)

If he enters an ROTC basic program and is physically qualified, he will gain a deferment as long as he remains in the program; this means at least a two-year deferment; if he gets into an advanced program (this applies only to Army and Air Force ROTC's, the Navy program is continuous) he is assured of two years more. Then, we hope, he gets his commission, serves three years and goes into the reserves. (Again we are perhaps looking too far ahead: if the demand for officers should fall off the percentage of men in ROTC programs might decline considerably, especially after the first two years of college.)

To sum up: if he enrolls in an ROTC unit, he is sure of two years of college and reasonably sure of an uninterrupted four years of college. Furthermore, the training he gets in his basic program puts him in a fair position to become an officer in one of the armed services, even if he fails to get into an advanced program and were to be drafted at the end of his two years of college. And perhaps it should be said at this point that it makes good sense, both from the point of view of the individual and of the national interest, for a person of intelligence and qualities of leadership to fit himself for service in a position where those qualities can be put to best use. Noblesse oblige, in other words.

Noblesse oblige, however, is a phrase that cuts two ways. Obviously not all men of military age can be officers. And I have talked with many a young man, without special military inclinations, who has said to me, in effect: why should I, just because my family can afford to send me to college, aim for a stripe on my sleeve or a bar on my shoulder, when most of the fellows I knew around home are going into the ranks? This point of view is not necessarily sheer quixotism. A boy I know who is planning to go to law school put it this way: "I've got to serve in the armed forces for at least two years, sooner or later. I don't know that it makes much difference to me when it comes. I'd like to get in and get it over with; if I get a commission I'll have to serve three years; I'd rather take my two years in the ranks and get back to my chosen career." This is an understandable point of view. For one must take account of this: though membership in an ROTC may insure an uninterrupted college education, that education is a seriously diluted one.

Most colleges require their students to take a five-course program each year; generally the ROTC course is substituted for one of these five courses; to put it in another way, an ROTC program absorbs one fifth of a man's college course. This may not seem too great a sacrifice, considering that it's the price one pays for getting an uninterrupted college education and at the same time making one's contribution to the national defense.

But let's be specific. Though Andy, you say, has not made up his mind as to his profession, he rather leans now toward medicine or engineering. A boy who wants to be a doctor represents perhaps a rather special case. If he's fairly young and is reasonably sure of his bent and aptitude, I'd almost be inclined to say: forget the ROTC; if he gets into his junior or senior year without being drafted and is accepted by a medical school, he is assured of deferment; the country needs doctors; he's serving both his own and the national interest by heading straight for his medical goal. And if he's to be a good doctor he needs all the liberal education he can get in addition to his medical studies.

The armed services, of course, need engineers. But engineers as well as doctors should have as much of a liberal education as possible. A prospective engineer has to have courses in the sciences - this means that a good part of his college course is prescribed for him from the beginning of his freshman year. In addition there are the courses in the humanities and social sciences (courses to satisfy "distribution" or "general education" requirements) which liberal college faculties have prescribed for their charges. I have talked with several boys in this category this year who came to college with a zest for the new experience, a desire to tackle fresh subjects and unexplored fields of learning, who see no prospect of an elective subject a subject they wish to study just for the love of it looming anywhere over the horizon. In fact, many of these poor souls will not be able to get in more than one or two of their "distribution" "or "general education" requirements until their junior year of college. If they have also to take two years of a foreign language and are in an ROTC it may indeed mean that their entire college career is, in effect, made up of prescribed courses.

A member of our faculty who has charge of proctoring the qualification test given for the purpose of determining student deferments told me the other day that the difference in attitude between this year's and last year's examinees was startling. The boys this year, he said, were much more indifferent to the whole idea. One reason for this indifference is probably the fact that many of these boys are enrolled in an ROTC unit and therefore feel reasonably sure of deferment. I suspect, however, that another reason is the bleak prospect they see before them with so few electives in sight. The liberal education they had looked forward to, in other words, is considerably less liberal than they had hoped. Compared to it their chances with the draft may not seem as unpleasant as originally they seemed.

Let me at this point hasten to say that the attitude of most students toward the cold war has seemed to me wholly admirable. They have faced the next few years with a common sense and calmness their elders don't always show. I have found very few men whose primary motive for enrolling in an ROTC is to duck the draft at all costs. Needless to say, none of the ROTC officers greet with enthusiasm candidates in whose bosoms this motive appears uppermost. On the other hand, I have found few young men who enter upon an ROTC program with the zest their officers would like to see. Like the rest of us, they face the uncertain future with a grim but scarcely alacritous determination to make the best of a bad situation.

I'm afraid what I've said has scarcely clarified things for either you or Andy. In conclusion, let me say that when Ive talked with freshmen in the last year or two about their future course of action I've generally based my comments on this premise: since we are obviously in for a long steady pull, it is important, both from the point of view of the national welfare and the individual student, that each man follow, insofar as he can, his natural bent, being diverted as little as possible from it by the exigencies of the military situation. So, my blessing to you: the decision has to be up to you and him; since it's his life, really up to him.

Yours ever etc.

P.S RE-READING this letter I see that I've left untouched the larger implications of your question. We've both been concerned with Andy's individual fate. But what of the impact of the draft and the inroads of ROTC courses upon liberal education? And what of the effect of this dilution of liberal education upon the struggle between totalitarianism and freedom which is the crucial issue of our time? That the dilution I speak of is a serious matter is indicated by the fact that at Harvard this year some 40% of the freshmen were enrolled in ROTC; at Dartmouth the figure was close to 75%. Even though these percentages should shrink somewhat in the years to come, the problem presented is one whose seriousness hasn't been sufficiently grasped.

In fact, through nobody's fault, we seem to have tackled the manpower problem posed by the cold war with a degree of improvisation that is perhaps typically American. Practically everyone now sees that our pell-mell demobilization after the war is largely responsible for our present troubles. A few cool heads advocated some form of universal military service after the war and advised somewhat less alacrity in beating our swords into plowshares; but the Administration, Congressmen of both parties and, above all, fathers, mothers, and men in the service thought no further beyond their noses than "to get the boys home." The military, to be sure, whose responsibility it is in fair weather and foul to provide for the national defense, sounded a note of caution. But their protests went largely unheeded or were considered the natural yelps of vested interests.

With the outbreak of the Korean affair we all went into a tailspin of pessimism which reached its nadir with the temporary debacle of the United Nations forces a year ago last fall. Colleges saw their enrollment vanishing almost overnight and hastily devised plans for acceleration by which I mean continuous year-round sessions despite the fact that educators universally agreed, on the basis of our war experience, that such acceleration was extremely undesirable. Fortunately the military situation in Korea improved; furthermore the armed services - less panicky than the educators made it clear that they had no desire for accelerated programs unless, of course, a total war made them necessary.

As a choice of two undoubtedly necessary evils, the extension of the ROTC programs is certainly a wiser approach to the plight of the colleges than acceleration, but the academic world, caught napping along with less sophisticated citizens, is only now waking up to the fact that a long-term view demands more serious attention to the inroads on liberal education inflicted by our present surrender of a fifth of the curriculum to what is essentially vocational training.

The view that liberal education is a luxury to be dispensed with in a time of austerity is, along with the wave of anti-intellectualism and the current distrust of ideas, one of the alarming symptoms of the possibility that we shall lose the contemporary war of ideas from within rather than from without. This was a point ably made by President Griswold of Yale in his Atlantic Monthly article of a year ago, "Survival is not Enough."

Nor will mere military might assure our survival. President Tucker of Dartmouth, during the first World War, put very cogently the predicament we find ourselves in:

Modern civilization, he said, has been by distinction a civilization of power. ... In what has thus come to be the habitual reliance upon material power we have, I think, the explanation of the otherwise strange contradiction in the experiences of the modern man; on the one hand, a sense of power rising at times to arrogance, and on the other hand, a sense of helplessness involving at times an abject surrender to the environment.

Our arrogance: reliance upon the atom bomb and the frequent demands for a preventive war; our helplessness: the extent to which we have surrendered to the materialistic view of history and the inevitability of violence which is the essence of Marxism.

Yet we continue to profess and possibly to believe that the salvation of our western culture rests not in science and technology but in a more penetrating examination of the nature of man and the relations of men to one another which only a greater knowledge of the humanistic disciplines can supply. And these are the very disciplines truly to be considered primary weapons in our arsenal - which are going by the board.

We are facing, for example, a shortage of engineers. I heard the other day that the Soviet Union is turning out annually forty thousand engineers: this was held up as the goal we must approximate. Doubtless it would be fatal for us to fall far behind. Yet it is equally fatal for us to think in merely quantitative terms. I also read recently that, though Soviet scientists were excellently trained and highly efficient, the dogmatic nature of the Soviet regime tended to hamper that bold and imaginative speculation upon which the greatest discoveries of science have always depended. We see even in the West how too narrow a scientific training may make a man a victim of the pseudo-science of Marxism: the career of the traitor Fuchs is a dramatic example. And just the other day so eminent a scientist as Joliot-Curie accepted quite without any attempt at verification the Communist charge that the United States was resorting to germ warfare in China.

We shall not, in short, preserve the humanism we boast as the heritage of western culture by turning out scientists and engineers who have little conception of the purposes for which, we believe, life is to be lived. Our leading educators have insistently in the past generation preached the dangers of specialization and the paramount necessity of general or liberal education if our culture is to be preserved. Yet specialization increases apace and, ironically, it is our scientists and engineers whose education is being dangerously curtailed by our military demands.

In belated recognition of this danger, faculties in our colleges and universities are tinkering with the curriculum to find ways by which men in the ROTC programs may gain more freedom for the pursuit of genuinely humanistic subjects. But so long as ROTC courses consume a fifth of the curriculum these devices are bound to be mere palliatives. If, as seems likely, the emergency we face is a matter of years and even decades; if therefore the demand for educated officers continues, we must, it seems to me, face the problem more radically and on a national scale.

President Griswold of Yale and Dean Kimball of the Thayer School of Engineering have, independently I believe, suggested that the technical training of ROTC men be concentrated in the summer months (for purposes of morale and of esprit de corps the minimum military drill might be retained during the regular college year). Men in these summer courses could be paid a sum to make up, at least partially, for what they might need to earn for their regular education. In this way the college year could be freed for the pursuit of a genuinely liberal education.

Apparently it is not too late for the colleges and the Department of Defense to consider some such approach to the problem. According to President Conant's report to the Board of Overseers of Harvard University, "a national policy in regard to ROTC units in the colleges is as yet undetermined; legislation dealing with this problem is still before Congress." A better reconciliation of our short-term needs and our long-term goals should somehow be attempted.

To hold the line against totalitarian aggression and at the same time to preserve the freedom, the humanistic tradition and the creative vigor of the western world without resort to war is the stupendous and complex task of our generation. It demands imaginative, adroit and far-sighted leadership on the part of our military leaders, statesmen and, above all, on the part of our educators.

DEAN STEARNS MORSE

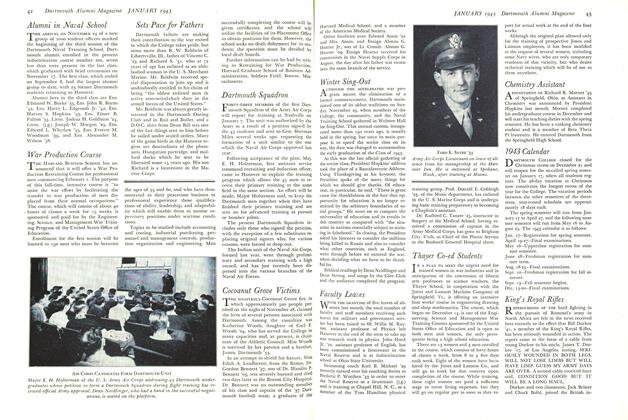

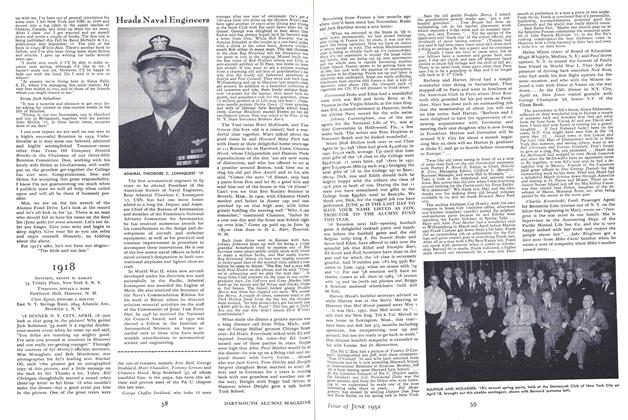

THE AIR FORCE ROTC at Dartmouth looked its smartest in April when the Inspector General of the First Air Force visited Hanover. The review took place indoors in the west wing of Alumni Gymnasium.

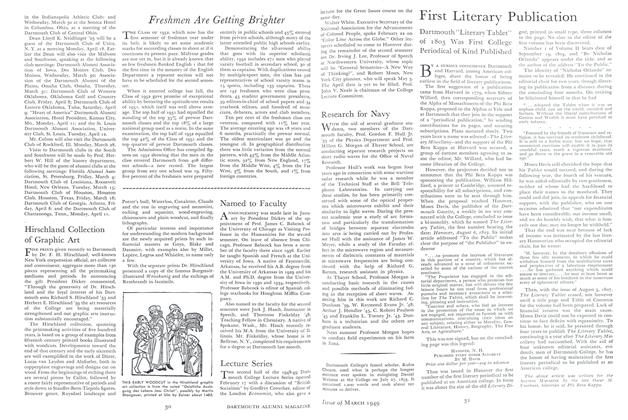

WEEKLY REQUIREMENT: THE NAVY ROTC (LEFT) AND ARMY ROTC STUDENTS WORK ON THEIR CLOSE ORDER DRILL ON CHASE FIELD

DEAN OF FRESHMEN

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDeaths

June 1952 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

June 1952 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1952 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1952 By CONRAD S. CARSTENS '52 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

June 1952 By OSMUN SKINNER, JOHN PHILLIPS, WILLIAM COGSWELL

STEARNS MORSE

-

Books

BooksTHE TEACHING OF ENGLISH: AVOWALS AND VENTURES

JUNE, 1928 By Stearns Morse -

Books

BooksTOLSTOY

JANUARY 1929 By Stearns Morse -

Books

BooksIN THE CLEARING.

May 1962 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksTHE LETTERS OF ROBERT FROST TO LOUIS UNTERMEYER.

JANUARY 1964 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksTHE MOON ALSO RISES.

FEBRUARY 1970 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksEmpty Rooms

September 1975 By STEARNS MORSE