Edited by Louis untermeyer. New York: Holt, Rinehartand Winston, 1963. 388 pp. $7.00.

Control, the discipline of form, restraint, understatement: these are characteristics of Robert Frost's poetry. Yet who can fail to see in it also the underlying passion ("To Earthward"), the subtlety ("The Subverted Flower"), the sense of the tragic, the cosmic, even ("Fire and Ice")? The valiant young friend who braved the elements with him at the Inauguration stressed this aspect, last October at Amherst: Robert Frost, said President Kennedy, was not simply the whimsical old man of the platform appearances, but one who had been acquainted with the night.

He was reticent. Though he used to say a poet was an exhibitionist, in his poetry he would let no one pluck out the heart of his mystery, he threw dust in the eyes. But in these letters to his old friend he lets himself go, lets us see the raw stuff of his life which was purified in his poems. Here we have his moods of dejection and self-criticism: in a letter of 1916, "The poet in me died nearly ten years ago"; a year later, "The conviction closes in on me that I was cast for gloom as the sparks fly upward"; fourteen years later, "I don't manage myself very well. I don't care if God doesn't care." And also his jealousy, his frank, sometimes harsh judgments of other poets, his sensitiveness about his "enemies": "Most of these were fancied," Untermeyer rightly says, "and his animadversions were not to be taken too seriously."

Here too is the sad record of those family tragedies which would have overwhelmed a less stalwart spirit: his mad sister, the death of his daughter, the suicide of his son ("Well then I'll be brave about this failure as I have meant to be about my other failures before"); the black days following his wife's death; his realization of the price paid ("I have caused suffering myself more or less justifiably in the process of getting anywhere"). One feels his need for understanding and friendship. (And here it should be said that Louis Untermeyer has kept himself admirably in the background, supplying only the comment necessary to understand the context of a letter.)

There is much else in these letters: the gaiety, the extravagant banter - dust in the eyes again; the observations on literature, on style ("how the writer takes himself and what he is saying"); the humanity, the wisdom. But I have chosen to emphasize the Frost his friends but not his vast public knew. For the letters reveal what the TimesLiterary Supplement said at his death: "man and poet have rarely been so much at one with each other."

Perhaps the one word for him is bravery. He wrote when he was "not much over twenty":

Even the bravest that are slain Shall not dissemble their surprise On waking to find valor reign, Even as on earth, in paradise; And where they sought without the sword Wide fields of asphodel fore'er, To find that the utmost reward Of daring should be still to dare.

This was the quality which drew him to John Fitzgerald Kennedy. To John Dickey, days before he died, he said that the great thing was courage.

Professor of English Emeritus

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePROJECT ABC

January 1964 -

Feature

FeatureThe Friends' Best Friend

January 1964 -

Feature

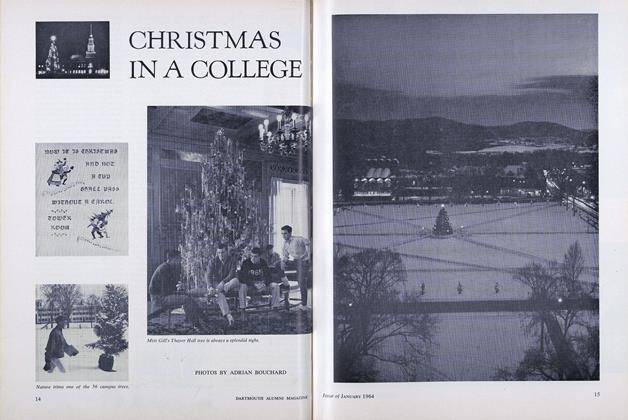

FeatureCHRISTMAS IN A COLLEGE

January 1964 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

January 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Class Notes

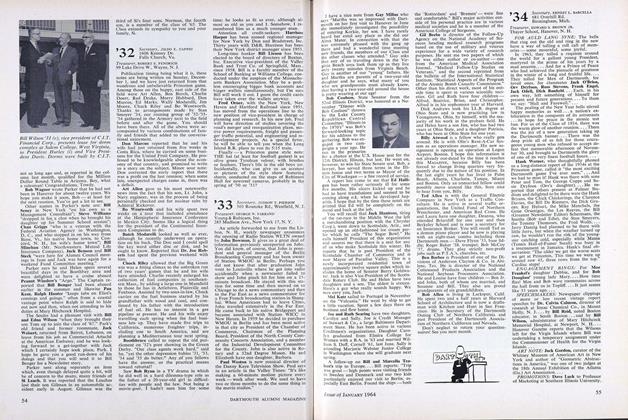

Class Notes1933

January 1964 By JUDSON T. PIERSON, GEORGE N. FARRAND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

January 1964 By WALLACE BLAKEY, HARRISON F. CONDON JR.

STEARNS MORSE

-

Books

BooksTHE TEACHING OF ENGLISH: AVOWALS AND VENTURES

JUNE, 1928 By Stearns Morse -

Books

BooksTOLSTOY

JANUARY 1929 By Stearns Morse -

Books

BooksTHE LOGIC OF LANGUAGE

November 1939 By Stearns Morse -

Article

ArticleThe Cold War and Liberal Education To a Father From a Dean

June 1952 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksIN THE CLEARING.

May 1962 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

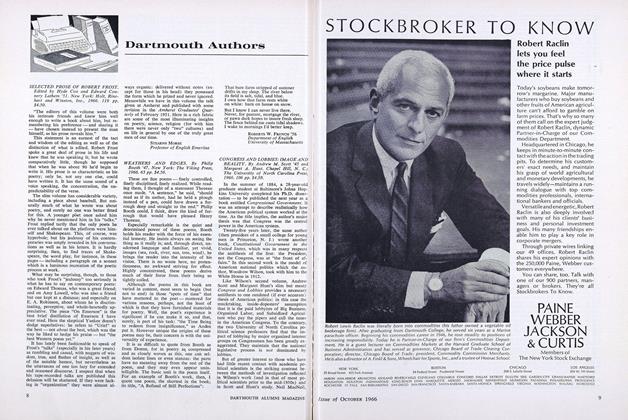

BooksSELECTED PROSE OF ROBERT FROST.

OCTOBER 1966 By STEARNS MORSE

Books

-

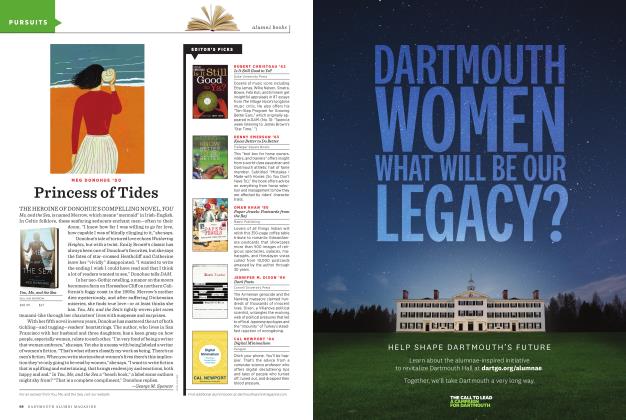

BOOKS

BOOKSEditor’s Picks

MAY | JUNE 2019 -

Books

BooksIt Matters

September 1980 By D.A.D. -

Books

BooksSPINDRIFT

November 1951 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksTHE KINGS DEPART. THE TRAGEDY OF GERMANY: VERSAILLES AND THE GERMAN REVOLUTION.

APRIL 1969 By JOHN CLINTON ADAMS -

Books

BooksKAZANTZAKIS AND THE LINGUISTIC REVOL UTION IN GREEK LITERATURE.

JUNE 1973 By KATHERINE LEVER -

Books

BooksAMERICA'S VIETNAM POLICY: THE STRATEGY OF DECEPTION.

APRIL 1967 By PAUL LEARY