By Sidney Cox, Assistant Professor of English, Dartmouth College. New York: Harper and Brothers. 1928.

I like better Mr. Cox's original title for this book NOT REALLY A CLASS—because THE TEACHING OF ENGLISH as a title says at once too much and too little. Mr. Cox would be the first to admit that English cannot be taught (except possibly by accident now and again.) And if that is the case a treatise on the subject the teaching of the unteachable, to use Professor Richardson's word—might seem an approximation to zero. But Mr. Cox's book is not a treatise nor does it confine itself to the teaching of English, and that is why, I say, that his title says too little.

For Mr. Cox realizes fully that, if there is any justification for the teaching of English and often enough this justification seems profoundly dubious but if there is any justification, it lies in an attempt to make students live more wisely, more fully, more richly for having touched here and there through a book or a teacher someone who has had moments of wisdom and richness. The sub-title, then AVOWALS AND VENTURES is more nearly expressive of what Mr. Cox's book really is: it is a highly personal and it is a venturesome book. Not that Mr. Cox has worn his heart upon his sleeve but he has attempted in this book to set forth simply and without solemn attempts at "impersonal formulations" just what he offers to his classes, to his students. And that is: "not my point of view, nor my knowledge, nor my schemes for getting knowledge, nor my technique, nor my discipline not any of these things, but friendship."

That, then, is the matter of this little book. Obviously, it has nothing to do with the methods, techniques, procedures, systems, with any of the devices, tests, tricks and gadgets that modern pedagogy has been so ingenious in inventing. For those trusting thirsty souls, therefore, who are looking for an aid to teaching which will be as specific as a Ford instruction book this book will be of little use. But for those who believe with Mr. Cox that teaching is one of the arts and who are trying however clumsily and unsuccessfully to put that belief into practice this book should offer support and hope and counsel.

It is where Mr. Cox shows himself in the act of practising his art that I think he is most venturesome and most successful. In the portion of his book called "For Instance" Mr. Cox has given us days with his classes a day with "Tess of the D'Urbervilles," for example, A Composition Lesson on Gene Tunney's Theory About Fighting, and A Harangue in Conference. An hour in a classroom is so fluid and evanescent a thing and also, it must be admitted, sometimes so spotted with dull, trivial, frivolous moments that an attempt to freeze it into cold print might give anyone pause: it requires address and a brave sort of honesty. For the temptation would be, of course, to select one of one's best hours, then to dress it up, to glide over the weak places, to shape it forth a rounded triumphant whole. But this Mr. Cox has not done. He has chosen, here and there, one of his hours that has seemed to go well and reported it with an admirable flexibility and simplicity so that the impression of an intellectual and emotional give and take between him and his students, of fluidity, movement, process, growth is admirably preserved. That seems to me no mean achievement. Of that and of the book as a whole one can say this: that in simplicity and yet subtlety of expression, in toughness, doggedness, richness and yet humility of thought Mr. Cox reveals himself as a teacher to be of the race of Socrates. What more can one say of a book about teaching than that?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

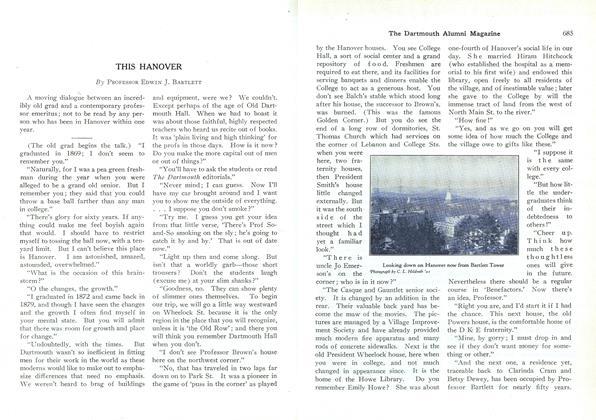

ArticleTHIS HANOVER

June 1928 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett -

Article

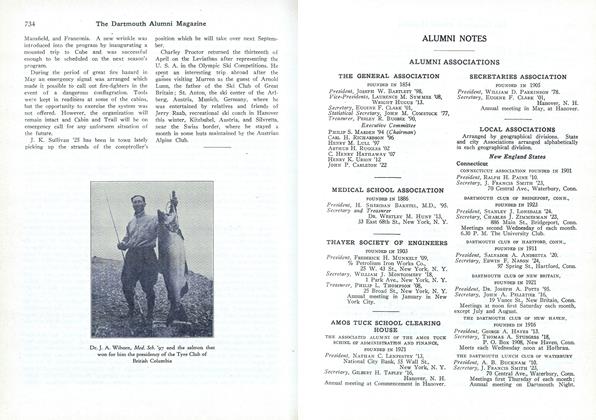

ArticleALUMNI ASSOCIATIONS

June 1928 -

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1878 AT DARTMOUTH REVIEWED IN 1928

June 1928 By Rev. George H. Gilbert D. D., '78 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1928 -

Article

ArticleA DARTMOUTH ODYSSEY

June 1928 By Myles Lane '28 -

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES ASSOCIATION

June 1928

Stearns Morse

-

Books

BooksADVENTURES IN WORLD LITERATURE.

June 1937 By Stearns Morse -

Books

BooksTO THE GOLDEN SHORE. THE LIFE OF ADONIRAM JUDSON.

January 1957 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksTHE STORY OF MOUNT WASHINGTON.

June 1960 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksIN THE CLEARING.

May 1962 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksSELECTED LETTERS OF ROBERT FROST.

DECEMBER 1964 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksSELECTED PROSE OF ROBERT FROST.

OCTOBER 1966 By STEARNS MORSE

Books

-

Books

BooksShelflife

Mar/Apr 2006 -

Books

BooksAlumni Books

NovembeR | decembeR -

Books

BooksTHE STORY OF WRITING: FROM CAVE ART TO COMPUTER.

MARCH 1963 By ADELAIDE B. LOCKHART -

Books

BooksBravey Heart

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2021 By DAVID ALM -

Books

Books"Rural Problems of Today"

May 1919 By H. B. P. -

Books

BooksFurther Mention

APRIL 1973 By J. H.