The President's Letter

To THE EDITOR: In June of 1951, in his statement on "Freedom of the Student Press," President Dickey said: "—on balance I am clear that I would not alter this core principle of American life by one jot. I say that because I believe that to do so would be to take the first firm step toward altering the best in the character of America and thereby really opening the way for enthroning here the errors and evils which we abhor in so many other parts of the world."

In that same article, President Dickey said: "As every student and practitioner of the subject knows, it is almost inevitable that a little censorship leads quickly to more."

I can not reconcile the words above with President Dickey's October letter to the editor of The Dartmouth.

As the President's letter stands it accomplishes two things:

First, it injects a dose of fear into Robinson Hall among young men who are learning to walk alone and who, like all men so engaged, are extremely vulnerable.

Secondly, it constitutes a salaam to the frightened men who never settle for just one salaam.

Bronx, N. Y.

[Mr. Gilroy was Editor-in-Chief of The Dartmouth in 1949-50. President Dickey's letter printed in our June issue gave support to the principle of uncensored editorial expression in the student daily. His October letter to The Dartmouth did not alter that general position but did state that no student editor at Dartmouth would be wise to wager very much on the assumption that the College would follow a course different from that of the University of Chicago, which forced the editor of The Maroon to resign for participation in a Communist-sponsored activity.]

Sidney Cox

To THE EDITOR: The change that marks the death in each of us of whatever is mortal in our nearest friends came to his students with the death of Sidney Cox. That he was one of the great teachers we believed when, as undergraduates, we realized his—in our experience at least—unparalleled capacity to give an edge and a force to the thoughts and feelings of each of us. Our belief was strengthened with the ensuing years in which his standards of excellence, his courage, his fidelity to the moral and spiritual values that are brought into being by the living imagination, returned to us as measures for our actions and ourselves. One who has known Sidney Cox as a teacher knows deeply that, to abound, life and art must grow to form through experience enriched with the best humanity can afford of thought and feeling, both: must "flow to form, to flow, to form again."

With most teachers he respects, I think, a student falls into the way of holding up every piece of work he does in the course to the question, "Will this be what the professor is hoping for?" In the case of Professor Cox one assesses his deeds by that question years after he has left the course. I find myself asking, whenever I set pen to paper—as now—whether Sidney would be gratified o,r disappointed by the words I find.

The question has resided with my conscience, chiefly, since I was weaned from undergraduate status and no longer put my words to the direct test of his approval or censure. So, I expect, it will go on the rest of my.life, and so, I expect, it will with a large number of men, men who have learned, as my contemporaries and I learned, the eminence of Sidney Cox's judgment. The structure of the universe was altered, just a little, by Sidney's having lived in it. The change, now that he is no longer in Hanover, is not that the world can ever be just what it would have been if he had never lived, nor that with his death it will stop feeling the effects of his life: hundreds and hundreds of his students attest that. The change is in Sidney Cox's students and in everyone who knew him, to be affected by his imagination, his mind, and his spirit. We can't, any more, find Sidney in Hanover when we could use his advice and criticism, for Sidney no longer lives in Hanover. He lives in us.

Valley Falls, N. Y.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Article

ArticleThe Old Dartmouth Burying Ground

February 1952 By PROF. ARTHUR H. CHIVERS '02 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

February 1952 By ENS. SCOTT C. OLIN, USN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Article

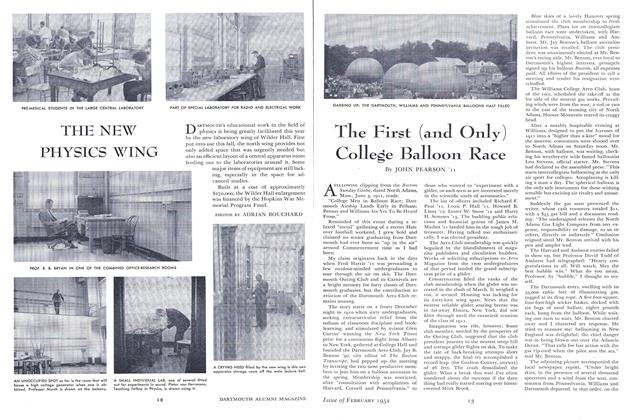

ArticleThe First (and Only) College Balloon Race

February 1952 By JOHN PEARSON '11 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

February 1952 By WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, JACK D. GUNTHER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

February 1952 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS, GILBERT N. SWETT

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

February 1962 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

APRIL 1972 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JAN./FEB. 1979 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

November 1979 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

JANUARY/FEBRUARY • 1987 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorReaders React

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014