A Reply to May

To THE EDITOR:

The June Undergraduate Chair article by Dick May '54 set forth three proposals: (1) that the first two years of the undergraduate curriculum be discarded or broadly reorganized; (2) that the College be made coeducational; (3) that the College dedicate itself to inculcating individualism.

Proposal (1) is based on the contention that the present introductory program lacks excitement due to narrowness in its courses and to poor teaching. I believe this contention fails to recognize that many undergraduates find excitement in discovering exactly the "highly specific" information which soured Mr. May on book learning - the answers to the questions, what, when, where and who. Admittedly the why question is ultimately more important. Yet it seems to me that a professor cannot expect a freshman to discuss why intelligently unless all the evidence has first been presented. Hence the "highly specific" introductory course.

As for the complaint against "narrowness," it might first be suggested that its opposite, "broadness," falls into the same category as those famous qualities "roundedness" and "wholeness." In 1952, The Dartmouth pointed out that "a whole man is one who has tasted all 28 flavors." The same might be said of a "broad" man. Most of us have had the treat of looking through the syllabi of "broad" introductory courses at other colleges such as the freshman course at a women's college in Massachusetts which treats the history of the western world from Adam through McCarthy, "with particular attention to broad trends and major figures."

Mr. May's peeve against compulsory language study seems to be based on the assumption that a foreign language is only a tool like the ability to type, which should be acquired according to some specific need. I would say that this assumption ignores the possibility that a language is a bridge through literature as well as conversation to new fields of ideas - the possibility that language study is intended to help in the process, as Robert Frost put it, of giving our present a past and future. Primary emphasis is usually placed on reading knowledge because literature is the contact with another language which most graduates are likely to have; but there are ample opportunities for speech training at Dartmouth for anyone who cares to pursue them. Some persons might add that foreign language study helped them to learn English.

Reading Mr. May's complaints against the science courses, I recalled that my experience in that field was not very happy; but I am aware that the fault did not lie with the courses or with the catalogue. I remember one course which was introduced with the confident instruction that nothing would be presented which could not be understood on the basis of F = MA. I wonder how much time a professor can afford for "the limitations" of physics, when it takes four months to explain the uses of F = MA. And as to the ruminations of the science majors, I can only submit that if they "thought about the implications of their discipline," they might not be science majors.

"There is no creative thinking involved, only rote memory of pre-digested textbook aphorisms," says Mr. May in his discussion of lower division teaching. It seems to me that "pre-digestion" is an important function of a professor teaching beginners. It may help them to save enough time to do some original thinking.

Mr. May sums up his first recommendation with the instruction that Dartmouth should let the new student know "how pitifully little he knows, how much there is to be learned and how important it is that he learn." Most freshmen need not be told the first two points. The third requirement will not be met by deemphasizing facts for the ignorant, disregarding language study for the deaf and dumb and discussing motives of science with men who haven't yet learned to handle the formulas.

In proposal (2), Mr. May states that he would make the College coeducational. There is already one high school in Hanover.

As for proposal (3), it seems to me that Dartmouth is already a vocal champion of liberalism and individualism. That these ideals fail to establish themselves in many cases cannot always be blamed on the College. But proposal (3) might well be accepted in the spirit of rededication.

All of this is not to deny that there are many phases of the introductory curriculum which could use a needle. Perhaps it says only that the grade you give your teacher depends on the marking system you use.

USS Missouri (88-63)U.S. Pacific Fleet

Revieiu Called Inadequate

To THE EDITOR:

I regret that Professor Wright's resume (for it is not a review), of my book The RomanCatholic Problem does not give an adequate idea of the book and fails completely to offer any constructive criticism. He cites from a footnote the supposed oath of the Knights of Columbus but omits my qualifying participle "supposed" thus conveying the impression that I accept the oath as gospel truth. Its publication in The Congressional Record does not make it that. To atone for this omission he made a far more important one in ignoring one O'Connor. This choice American, in a very critical year of the last war when the Vatican was allied with Hitler, advocated in the Jesuit periodical America (March 1941) the overthrow of our democracy by the Catholic laity under the leadership of its hierarchy. The proposal was the more significant and serious because it was inspired by the collapse of Belgium and France and the resultant increased danger to England and the United States, the bulwarks of freedom. O'Connor's treason is quoted on two successive pages of my book, not in a footnote. The lurking danger of O'Connor's proposal was obvious to every alert American but apparently made not the slightest impression upon the apathetic summarizer of The Roman Catholic Problem.

What Wright fails to realize is that my book seeks to defend the traditional ideals of our country the deliberate violation of which justifiably invites drastic denunciation. His concluding; paragraph, "I beg, to assure readersthat the views summarized above are exclusively Professor Elderkin's - by no means myown," rejects my book in toto, the quoted pronouncements of the Vatican, its obviously un-American policies and actions and the seemingly reasonable deductions from these pronouncements, policies and actions. This timorous entreaty suggests that Wright is a suppliant in the arena of religious controversy where he trembles at the sight Of a papal bull.

Princeton, N. J.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

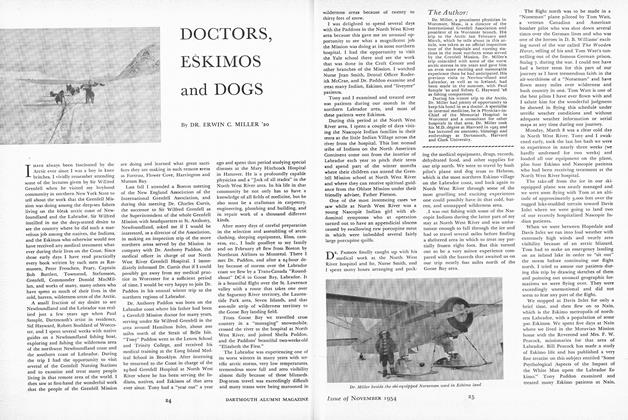

FeatureDOCTORS, ESKIMOS and DOGS

November 1954 By DR. ERWIN C. MILLER '20 -

Feature

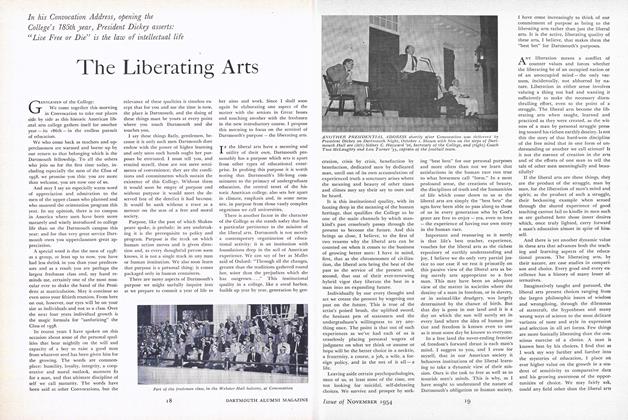

FeatureThe Liberating Arts

November 1954 -

Feature

FeatureA Backward Glance at the Humanities

November 1954 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1954 By G.H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Article

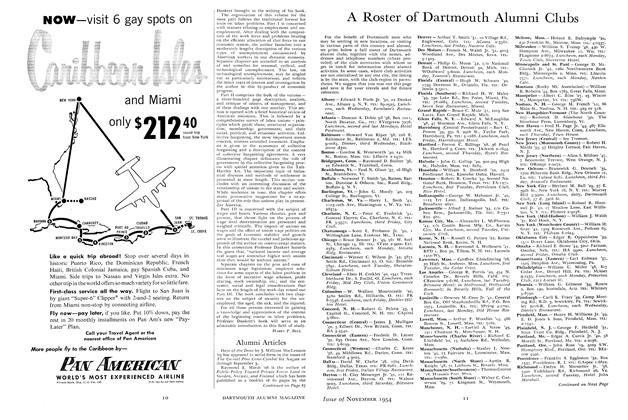

ArticleA Roster of Dartmouth Alumni Clubs

November 1954

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

January 1941 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

FEBRUARY 1968 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

March 1981 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Sept/Oct 2011 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorReaders React

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014