LACK of space prevents any palaver, but I must say a few words about Lloyd Goodrich's book on John Sloan, issued by Macmillan, bound at $3, and by the Whitney Museum as an unbound catalogue of the John Sloan Retrospective Exhibition for $1. (This show, magnificent and far greater than my high expectations, ended in New York on March a, but was to go to the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, and later to the Toledo Museum of Art.) Mr. Goodrich as artist, writer on art, friend of Sloan's, and director of the Whitney Museum is eminently qualified to write on Sloan as man and painter, and here in less than a hundred pages he does so admirably. He gives the essential facts of Sloan's long life, recounts the history of the "Eight," of whom Sloan has the best chance of immortality, and ends with Sloan's death in Hanover on September 7, 1951. There are many reproductions, several in color. Of Sloan's last summer in Hanover your browser has written an essay about which you may hear a little later.

A volume which I got around to reading only recently is Richard D. Altick's The Scholar Adventurers. He writes about how scholars work, of certain well known adventures in scholarship (and some not well known) such as Leslie Hotson's running down in the London Public Records Office in Chancery Lane the real facts concerning the death of Christopher Marlowe, of the exciting truth about Sir Thomas Mallory who wrote the incomparable Morte d'Arthur, of the discovery of the many, many, but none too many Boswell papers, and of how John Carter and Graham Pollard proved the most famous bibliographer of our century to be a forger, and other fascinating bits of lore. In this book the generally unsung scholar comes into his own.

Readers of H. M. Tomlinson's classic The Sea and the Jungle (1912) will greatly enjoy, I think, a new book issued by Cape in London called A Wilderness Voyage, which describes a trip to Buenos Aires via the Amazon, the Madeira, and the Mamore rivers. The author, Peter Grieve, I regret to say, died in New Delhi in September 1950. A great pity, as he was a most promising writer.

The books of Percy Lubbock, the English author, are relatively unknown to American readers. His books, especially The Craft of Fiction, Earlham, Roman Pictures, and Portrait of Edith Wharton are really first-class works in criticism and belles lettres. This past month I read for the first time his Samuel Pepys, which turned me back to dip once again in the Wheatley edition of nine volumes, of which I have now read five. Pepys should be read in small doses, but he does give a magnificent picture of the seventeenth century, and reveals himself most intimately as a self-centered, genial, kindly, shrewd, and successful member of society. The Church of St. Olave's, Hart Street, London, where he and his wife lie, was partially destroyed by Hitler's bombs. (See J. M. Richard's book of photographs: TheBombed Buildings of Britain, second edition, 1947.)

A really remarkable book on birds is Len Howard's Birds as Individuals, with a foreword by Julian Huxley. The author lives alone in a Sussex cottage surrounded by wild birds which have the freedom of her house and grounds. They have lost all fear of her, and she has had a remarkable, even unique, opportunity of observing them and their habits. She estimates the degree of their intelligence with almost demonstrable certainty though Mr. Huxley, the scientist, warns about accepting all her findings. Every serious ornithologist will want to read this book. Eric Hosking's photographs add greatly to its interest.

Gregory Hines of the Economics Department recommended to me a Gaelic novel Rain on the Wind by Walter Mackin, and though I don't entirely share his enthusiasm, I enjoyed it. It is the story of an Irish lad Mico and his love for Maeve. The wild setting is beautifully described. The novel is sentimental at times, and as tempestuous as the storm which blows in from the Irish Sea, and in its own peculiar Celtic way is a powerful book.

A re-reading of Melville's Typee, with a lot of enjoyment because of its still fresh quality, turned me back to Richard Chase's ( 37) Freudian study of Melville published in 1949. Then I turned to re-read Omoo, not as good as Typee, and then to one far greater than either, Moby Dick. A new centennial edition of this has appeared with nearly goo pages of explanatory notes. This has been edited by two Melville scholars, Luther S. Mansfield and Howard P. Vincent. It is a book two and three quarters inches thick, but not a hair too thick for me.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Fund Makes Strong Start in Its 1952 Campaign

April 1952 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1952 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

April 1952 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS, HOWARD A. STOCK WELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

April 1952 By ENS. SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III, GLENN L. FITKIN JR. -

Article

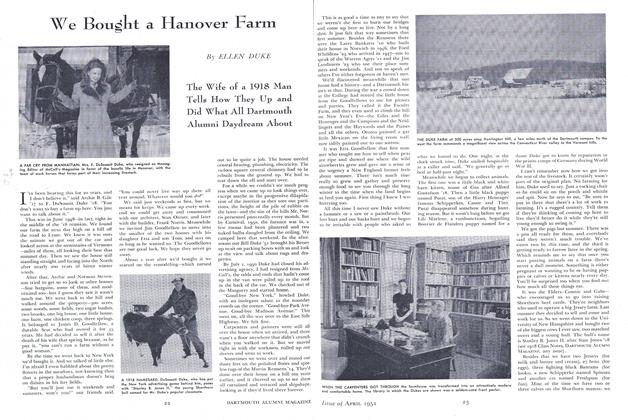

ArticleWe Bought a Hanover Farm

April 1952 By ELLEN DUKE

HERBERT F. WEST '22

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

November 1934 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

June 1938 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1948 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksTHE WINOOSKI,

June 1949 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksA CAMP AQUATIC PROGRAM,

June 1949 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

By HERBERT F. WEST '22

Article

-

Article

ArticlePHI KAPPA PSI COUNCIL WILL MEET AT HANOVER IN APRIL

April 1921 -

Article

ArticleClub Officers Annual Meeting

DECEMBER 1970 -

Article

ArticleTrustees Take Action

MAY 1983 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Winter Prophet

December 1992 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1960 By ALAN M. SHAVER '60 -

Article

ArticleIt's Just Like Talking to People

APRIL 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84