Annual Undergraduate Issue Carries Brief Reviews From Students on Their Recent Reading

A FEW SENIORS WERE ASKED for book recommendations for this Undergraduate Issue, and as their findings have proved interesting to the alumni in the past, I feel sure that this year will prove no exception to the rale.

Robert S. Kinsman, of Framingham, Massachusetts, one of the Senior Fellows this year, and the recent recipient of a Dartmouth Fellowship which will enable him to carry on his English studies at Yale next year, (he is an English Major) will lead the batting order: "The one book that made the deepest impulsions upon me, the past year, was the anthology The Complete GreekDrama, compiled by Oates and O'Niell, The grandeur and loftiness of Aeschylus' massive strength; Sophocles' grace and beauty defining sharply the nature of man, his passions and struggles; the realistic art with which Euripides paints, frankly and straight-forwardly, the most furious passions; the ribald salt of Aristophanes smarting its way into the decaying blubber of Hellenism; Menander's light fancy; combine into an architectonic memorial to the universality and timelessness of great teachers and creators.

"To the so great number of us, 'astray gone,' entangled in the gloomy wood of post-war and pre-war confusion, Dante's Divine Comedy furnishes Beatrician light and inspiration. I am not able to comment sagely or criticize validly, for such a work •s far beyond my ability to know really without the devotion of a life-time's study. Any man who has experienced the saltsavour of other's bread and knows 'How hard the passage to descend and climb by other's stairs,' is entitled to deeper consideration than pragmatic sociologists will allow. I should like very much to acknowledge my profound debt to Professor George C. Wood's penetrative analysis and commentary that only Mr. Wood can provide from a sea-deep fund of wisdom.

"Catherine Carswell's The TranquilHeart, a life of Boccaccio, is a rapid and deep-scouring biography. Miss Carswell is as good a scholar as Hutton, her early twentieth century biographical predecessor, adding, as well, a more vivid flavor of the times and events she is portraying.

"The great shroud of the sea, the image of the ungraspable phantom of life heaves and swells in Melville's Moby Dick. The poetic quality of his prose, the wave-like roll of his rhythm, his profound probing of the problem of malice in the Universe, make this book of lasting value.

"Would that we could as gladly learn as these books teach!"

John I. Fitzgerald Jr., of Boston, Massachusetts, a friendand fellow student of mine, who is majoringin History, wrote as follows: "The Trilogy, composed of With Fireand Sword, The Deluge, and Pan Michael, by Henryk Sienkiewicz. Published by Lit-, tie, Brown & Co., 1890.

"These titles form a group of realistic writings based on the past glories of Poland. Sienkiewicz, Nobel Prize Winner in 1905, employs the novel to stimulate in the Poles the sense of nationality that had swept over the rest of Europe earlier in the 19th century. These books have never attained the prominence that they deserve in this country.

"Since Yesterday, by Frederick Lewis Allen. Harper, 1940.

"An excellent review of the past decade of our history, the events of which affected the individual lives of all of us.

"Tammany Hall, by M. R. Werner. Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1938.

"This is the story of the political organ- ization that has shaped the destinies of New York City. It is an interesting account of the men who have made Tammany what it is, and who were themselves formed by the machine with which their fortunes were involved. This book offers an excellent opportunity with which to see the effects such institutions have had on America."

C. Whitney Miller, captain of this year's football team, hails from Seattle, Washington, and is majoring in Geology. His recommendations follow: "Candle in the Dark, by Irwin Edman.

"A bit of personal philosophy by the author with which he hopes to aid those who are downhearted and discouraged with the world in which we live and with the futile strivings of mankind. One must remember that things have looked black to others in the past and that tomorrow may bring the morning star.

"Dark River, by Nordhoff and Hall.

"The beauty and freshness of tropic islands is blended here with the simple but complete life of the natives. Along comes a young, well educated English lad who finds there are greater things in this world than fame, money, and social conformity to civilized ways. Happiness, adventure, and utter tragedy staggers the serene islands as a beautiful romance bring with it death and a series of events which should encourage even the most unsatisfied to remain within his own society.

"Attending Marvels, by G. M. Simpson.

"Simpson's experiences in Patagonia and his observations of the physiography of the country, the wild life, the habits and customs of the backward people make a fascinating book. A good picture of how a geologist goes about his work is also revealed, and the hardships and peculiar circumstances which meet him at every turn turn his escapade into a romantic and perilous trip.

"The Founders of Geology, by Sir Archi- bald Geikie.

"Every natural observer should read this historical sketch of the science of geology. Beginning with the Greeks, Geikie traces the opinions and beliefs held by different men as to the character of the earth, the origin of surface physical features, and the cause of volcanoes and sedimentary beds. The life histories of such famous geologists as DeSaussure, Werner, Smith, Hall, Agassiz, Hutton, Logan, and Sorby are used to illustrate the different stages of scientific geologic thought and to help us appreciate the knowledge we have today."

Owen Arthur Root, of Brooklyn, New York, has been a 4.point man ever since he entered college, is now a Senior Fellow, and has received a Dartmouth Fellowship for further study next year. His is a Topical Major on International Relations. He recommends: "Ecce Homo, by Friedrich Nietzsche.

"Behold the prophet of the World War, the man who saw that the decadence and sterility of the late nineteenth century Europe could be redeemed only by the most terrific upheaval the world has ever seen. This autobiography, written at white heat with Nietzsche's passionately tart and racy style at its peak, is not a review of the events of his life. It is rather a reaffirmation of his vision and a declaration of his fatality. In this book the Transvaluer of all Values writes his name into world history after 1914.

"Out of Revolution: the Autobiographyof Western Man, by Eugen RosenstockHuessy.

"The theme of this history, which, like life itself, fuses into one unit politics, law, literature and philosophy, is the unity of mankind proved by the self-revealing character of the Great Revolutions in the history of our era. By listening to the very man caught in these historical events, and, under pressuie of life and death, forced to reveal their inmost desires and faith, we are able to renew our kinship with those in the past who made possible the liberties and loyalties of our own day. Only by doing so, we are warned, can we gather strength and direction to ensure a future for ourselves and posterity.

"Tremendous Trifles, by G.K.Chesterton.

"In the title lies the key to Chesterton's brilliance as critic and social interpreter. Trifles like a piece of chalk, a street-corner placard, and lying in bed, take on tremendous proportions as they are shown to A book like this reinforces one's joy in living. How can it be otherwise when the author is a man whose every word reflects the creed that 'About the whole cosmos there is a tense and secret festivity like preparations for a great dance!' "

Richard E. Glendinning Jr., of Ridgefield, Connecticut, who has ably conducted this year the column on undergraduate activities for the DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE, is majoring in Sociology and herewith reviews a sensational Spring novel.

"Native Son, by Richard Wright.

"It is not a pretty story that Mr. Wright tells in this novel but the people he tells about, the lives they live, the things they think, and the patterns they conform to are not pretty either.

"Bigger Johnson, the coal-black negro with a mind as murky as an African jungle but as simple as an elementary book in Arithmetic, is an object for a psychologist's study. He has been thrown into a self-conscious negro group like a piece of coal thrown on the heap which can regain its identity by being tossed in the fire to glow fiercely for a moment and then be demolished. The fire he finds himself in is the charge of raping and killing the daughter of the wealthy white family for whom he works. The first part of the charge is false; the second is true but accidental. Bigger becomes a hunted animal but just as animallike as he are the whites who smell the chance for a blood revenge.

"Richard Wright asks for no sympathy for Bigger but he gives him a motive which is greater than any man, and is as large as society itself. Whites are the negroes' land- lords; whites are their bosses; whites fly the airplanes, drink cocktails, have experi- ences—the niggers are the laborers. Bigger never knew a negro who could command the respect of a white, or the fear of a white, or stir the emotions of a white, but with his single action there isn't a white man in Chicago who wouldn't like to get his hands on him. Bigger becomes an individual.

"Bigger is bad and detestable but it is the white bigotry, intolerance, and racial prejudice despite high-flown promises of a democratic spirit, which makes the reader mad. Native Son is for those whose mind,s are not set—it will show them the danger's, and for those whose minds are, it will show them their folly."

Thomas W. Braden Jr., is from Dubuque, lowa, is majoring in Sociology, and has just completed his tenure as editor of The Dartmouth.

Mr. Braden has been excited recently by Professor McQuilkin DeGrange's enthusiastic and masterly exposition of the Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte, and what he has to say is based on his readings in Comte. His remarks follow:

"All through Dartmouth's courses in the Social Sciences the problem of Democracy arises when for instance, majority rule on a certain question is in actual conflict with scientific procedure and with experience. (Statistics, for instance, tend to show that it is quite possible that in the future there will be enough people to make legal so stupid an economic plan as the Townsend Plan.) It becomes then not only interesting but actually exciting to be introduced in the last semester of one's senior year to Comte's Positive Philosophy. His book at once sums up the problem, ties together all of the intrinsically interesting, but seemingly unrelated courses in the department of Sociology, and poses a basis for a solution.

"Comte hits out equally hard at both the authoritarianism reflected in Fascist nations today, and the philosophy behind contemporary democracies. The attack on democracy hits our minds with the greater impact as we have been brought up on the basic beliefs of free press, free speech, sovereignty of the people, the theory that all men are equal, etc. Comte calls this kind of blind belief in generalizations intellectual anarchy. He shows by one example after another that this freedom is effective only in destroying authoritarianism, but that it leads to the control of ignoramuses, and the theory that every man's thinking is as good as anothers, which is palpably absurd.

"Comte's solution is definite. He proves adequately to me, at least, that if society is to progress it must be along the lines of positive, scientific working out of social problems, in much the same method as chemist's work out their problems in a laboratory. If this solution does not, at the very least, point the way, then it would seem that all education is fruitless."

UNDERGRADUATE LABORATORY WORK IN PLANT PHYSIOLOGY, CLASS AT CLEMENT GREENHOUSE.

PROFESSOR OF COMPARATIVE LITERATURE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

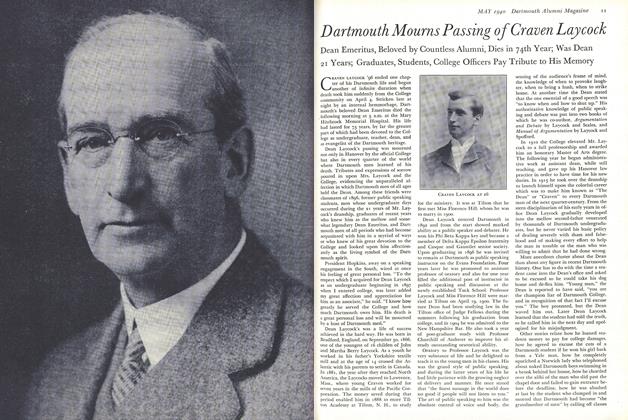

ArticleDartmouth Mourns Passing of Craven Lay cock

May 1940 -

Article

ArticleI Found Seven Latinos

May 1940 -

Article

ArticleJohn M. Mecklin, Teacher

May 1940 By Thomas W. Braden '40 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915*

May 1940 By CHARLES R. TAPLIN, RUSSELL B. LIVERMORE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

May 1940 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, H. WARREN WILSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935*

May 1940 By GARDNER CUSHMAN, DONALD W. FRASER

HERBERT F. WEST '22

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

May 1936 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover browsing

November 1938 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1941 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

January 1948 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

October 1954 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleWestholm Publications

December 1956 By HERBERT F. WEST '22