The Wife of a 1918 ManTells How They Up andDid What All DartmouthAlumni Daydream About

I'VE been hearing this for 20 years, and I don't believe it," said Archie B. Gile '17 to F. DuSossoit Duke '18. "You don't want to buy a farm up here. You just want to talk about it."

That was in June 1948—in fact, right in the middle of the '38 reunion. We found our farm the next day high on a hill off the road to Lyme. We knew it was ours the minute we got out of the car and looked across at the mountains of Vermont —miles of them, all looking their best that summer day. Then we saw the house still standing straight and facing into the North after nearly 200 Mars of bitter winter winds.

After that, Archie and Norman Stevenson tried to get us to look at other houses —fine bargains, some of them, and modernized too—but I guess they saw it wasn't much use. We went back to the hill and walked around the property—300 acres, some woods, some fields,.two sugar bushes, two brooks, one big house, one little house, one barn, one chicken coop, three springs. It belonged to James D. Goodfellow, a durable Scot who had owned it for 45 years. He had decided to sell it after the death of his wife that spring because, as he put it, "you can't run a farm without a good woman."

By the time we went back to New York we'd bought it. And we talked of little else. I'm afraid I even babbled about the pretty flowers in the meadows, not knowing then that a proper husbandman doesn't brag on daisies in his hay fields.

"But you'll just use it weekends and summers, won't you?" our friends said. "You could never live way up there all year around. Whatever would you dot We said just weekends at first, but we meant for keeps. We came up every weekend we could get away and communed with our architect, Stan Orcutt, and later with the builder, Frank Norris. Meanwhile we invited Jim Goodfellow to move into the smaller of the two houses with his daughter Etta and son Tom, and stay on as long as he wanted to. The Goodfellows are our good luck. We hope they never go away.

About a year after we'd bought it we started on the remodeling—which turned out to be quite a job. The house needed central heating, plumbing, electricity. The 10-foot square central chimney had to be rebuilt from the ground up. We had to tear down the ell and start over.

For a while we couldn't see much progress when we came up to look things over, except maybe in the progressive dilapidation of the interior as they tore out partitions, the height of the pile of rubble on the lawn—and the size of the bills Mr. Norris presented punctually every month. But by Carnival, 1950, the furnace was in, a few rooms had been plastered and two naked bulbs dangled from the ceiling. We camped here that weekend. In the afternoons our Bill Duke '51 brought his Betsey up to sit on packing boxes with us and look at the view and talk about rugs and draperies.

By July 1, 1950 Duke had closed his advertising agency, I had resigned from McCall's, the odds and ends that hadn't come up in the van were piled up to the roof in the back of the car. We checked out of the Marguery and started home.

"Good-bye New York," howled Duke, with an inelegant salute to the noonday crowds on the corner. "Good-bye Park Avenue. Good-bye Madison Avenue." This went on, all the way over to the East Side Highway. We felt fine.

Carpenters and painters were still all over the house when we arrived, and there wasn't a floor anywhere that didn't crunch when you "walked on it. But we moved right in with the workmen, rolled up our sleeves and went to work.

Sometimes we went over and rested our dusty feet on the polished floors and spotless rugs of the Martin Remsens '14. They'd done over their house on a hill ten years earlier, and it cheered us up to see them all curtained and terraced and shipshape, looking as if they'd lived there forever.

This is as good a time as any to say that we weren't the first to burn our bridges and come up here to live. Not by a long shot. It just felt that way sometimes that first summer. Besides the Remsens there were the Larry Bankarts 'to who built their house in Norwich in 1946, the Ford Wheldens '25 who arrived in 1947—not to speak of the Warren Agrys '11 and the Jim Landauers '23 who use their place summers and weekends. And not to speak of others I've either forgotten or haven't met.

We'd discovered meanwhile that our house had a history—and a Dartmouth history at that. During the war a crowd down at the College had rented the little house from the Goodfellows to use for picnics and parties. They called it the Faculty Farm, and they even used to climb the hill on New Year's Eve—the Giles and the Heneages and the Campions and the Neidlingers and the Haywards and the Pianes and all the others. Orozco painted a gay little Mexican on the living room wall, now tidily painted out to our sorrow.

It was Etta Goodfellow that first summer who taught me how to tell when peas are ripe and showed me where the wild strawberries grew and gave me a sense of the urgency a New England farmer feels about summer. There isn't much time really to grow and gather and preserve enough food to see you through the long winter to the time when the land begins to feed you again. First thing I knew I was hurrying too.

All this time I never saw Duke without a hammer or a saw or a paintbrush. Our feet hurt and our backs hurt and we began to be irritable with people who asked us what we found to do. One night, as the clock struck nine, Duke smiled hospitably at a caller and said, "We generally go to bed at half-past eight."

Meanwhile we began to collect animals. The first one was a little black and white barn kitten, name of Gus after Alford Gustafson '18. Then a little black puppy named Putzi, son of the Harry Heneages' famous Schipperkes, Cassie and Tiny. Putzi disappeared somehow during hunting season. But it wasn't long before we got Lili Marlene, a rambunctious, beguiling Bouvier de Flandres puppy named for a dame Duke got to know by reputation in the prison camps of Germany during World War II.

I can't remember now how we got into the rest of the livestock. It certainly wasn't part of the original plan. No farming for him, Duke used to say. Just a rocking chair so he could sit on the porch and whittle and spit. Now he says to me, "Be sure to put in there that there's a lot of work to farming. It's a rugged country. Tell them if they're thinking of coming up here to live they'd better do it while they're still young enough to swing it."

We got the pigs last summer. There was a pen all ready for them, and everybody said they weren't much trouble. We've eaten two by this time, and the third is getting ready to farrow later in the spring. Which reminds me to say that once you start putting animals on a farm there's never a dull moment. Something is either pregnant or wanting to be or having puppies or calves or kittens nearly every day. You'll be surprised too when you find out how much all these things eat.

It was the Elders—Connie and Gabewho encouraged us to go into raising Shorthorn beef cattle. They're neighbors who used to operate a big Jersey farm. Last summer they decided to sell and come and work for us. So we went down to the University of New Hampshire and bought two of the biggest cows I ever saw, two matched steers and a young bull. The bull's name is Stanley B. Jones II, after Stan Jones '18. (see 1918 Class Notes, DARTMOUTH ALUMNIMAGAZINE, any issue) .

Besides that we have two Jerseys (for milk and butter and cream), 27 hens (for eggs), three fighting black Bantams (for looks), a new Schipperke named Spinoza and another cat named Freshpuss (for fun). Most of the time we have two or three calves on the Shorthorn mamas: we buy the calves from neighboring farmers to fatten and sell for veal.

After we get the maple syrup made this spriiig, the next big project is to start bringing back the hayfields. We have a tractor now and a haybaler. Today Duke bought a manure spreader. "Tell them," he says, and I know I shouldn t, that I'm right back where I started from. Only now it's New Hampshire instead of Madison Avenue."

There is something about this country that won't let you neglect it. I can't tell you what it is. I only know that we're farmers now, and we didn't mean to be. It is rugged, and it sustains some pretty rugged characters. Just the other day Duke took Jim Goodfellow, now in his eighty-third year, down to the clinic for a check-up.

"Do you ever get out of breath?" the doctor inquired in the course of the usual inquisition.

"No," Jim said humbly. "Only when I run."

Still, in one very important particular, Hanover is like New York or any other cosmopolitan city. You can see people as much or as little as you like. You can find people who will sing with you, or play bridge or Canasta with you, or hunt with you, or paint pictures with you, or join a movement to raise the teachers' pay, or sit and talk with you about existentialism. You can hear Marian Anderson, or watch a hockey game, or make a lemon pie for a food sale. Or sit home and do nothiing.

You may even have a skill the College can use part time—the way Ford Whelden works on fund-raising and Duke helps to lecture and drill the Air Force ROTC unit at Dartmouth.

But if you live on a hill the way we do and the Remsens do, you won't do any of these things from Thanksgiving until the first of May unless you have a Jeep. That's the first thing to buy. Without it, you're a sitting duck.

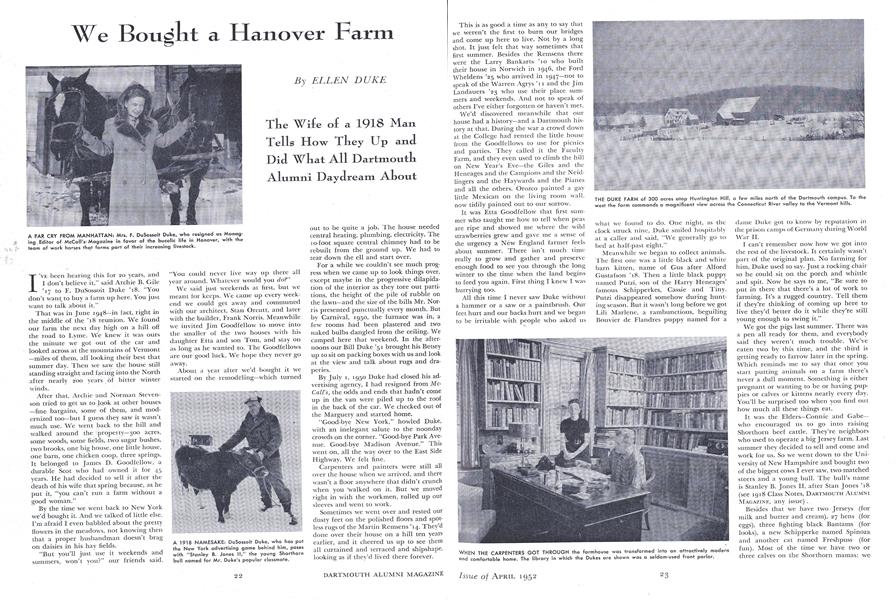

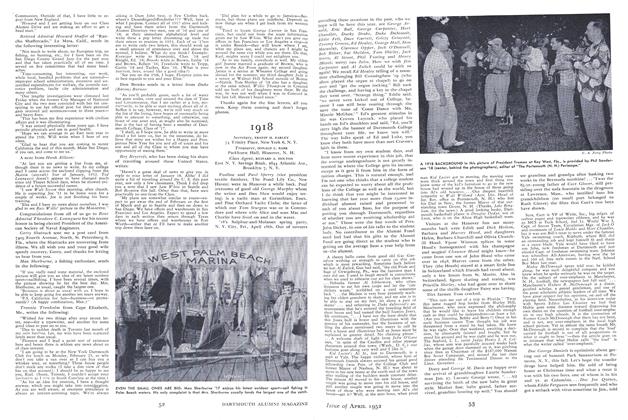

A FAR CRY FROM MANHATTAN: Mrs. F. DuSossoit Duke, who resigned as Managing Editor of McCallV Magazine in favor of the bucolic life in Hanover, with the team of work horses that forms part of their increasing livestock.

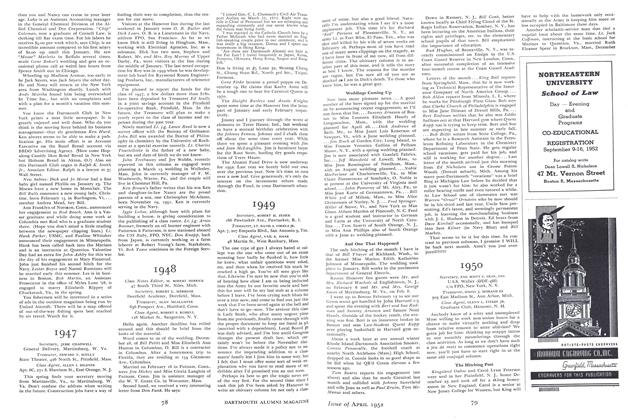

A 1918 NAMESAKE: DuSossoit Duke, who has put the New York advertising game behind him, poses with "Stanley B. Jones II," the young Shorthorn bull named for Mr. Duke's popular classmate.

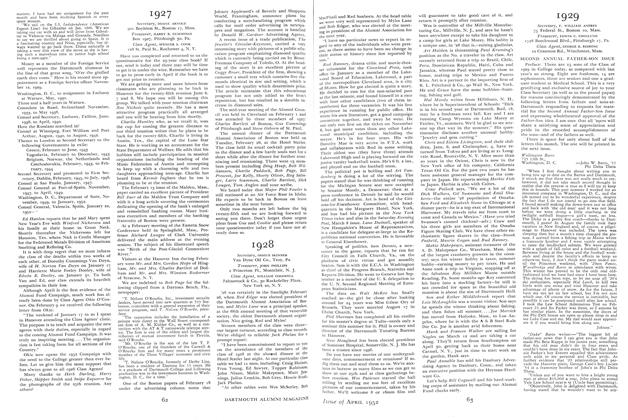

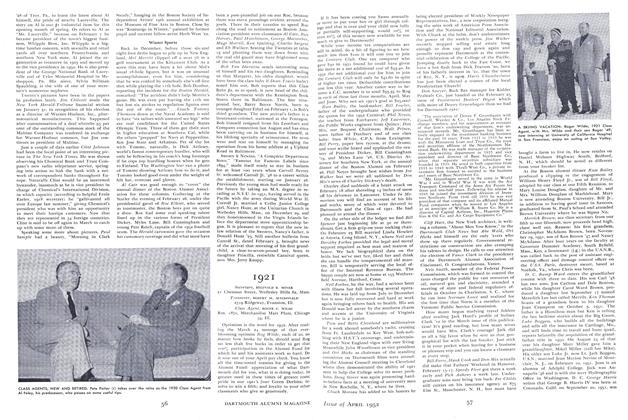

WHEN THE CARPENTERS GOT THROUGH the farmhouse was transformed into an attractively modern and comfortable home. The library in which the Dukes are shown was a seldom-used front parlor.

THE DUKE FARM of 300 acres atop Huntington Hill, a few miles north of the Dartmouth campus. To the west the farm commands a magnificent view across the Connecticut River valley to the Vermont hills.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Fund Makes Strong Start in Its 1952 Campaign

April 1952 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1952 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

April 1952 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS, HOWARD A. STOCK WELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

April 1952 By ENS. SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III, GLENN L. FITKIN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

April 1952 By REGINALD B. MINER, ROBERT M. MACDONALD, ROGER C. WILDE

Article

-

Article

ArticleFACULTY RETURNED FROM SERVICE

January 1919 -

Article

ArticleT. K. GEDGE '25 WILL BE ASSISTANT FOOTBALL MANAGER

November 1923 -

Article

ArticleFrom the Mailbag

June 1943 -

Article

ArticleCall of the Wild

July/Aug 2002 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

Mar/Apr 2005 By BONNIE BARBER -

Article

ArticleProf's Choice

NOVEMBER 1996 By Professor William Summers