A new and intriguing theory about the founding of Dartmouth College. If it had not been for a lovers' quarrel in England, could Eleazar Wheelock have gone to Yale and founded his Indian charity school?

RESTING for a moment in a small New York hotel while on a cross-country trip, I happened to pick up a book the title of which was Life in theColonies or something like that and found a curious statement to the effect that "Dartmouth grew out of a 'lovers' quarrel between Dean Swift and his worshipful Vanessa." The idea intrigued me a bit and I offer it for what it is worth without however doing any real research on the subject, a necessary task before any conclusion can be reached. I will say, however, that the idea is a plausible one.

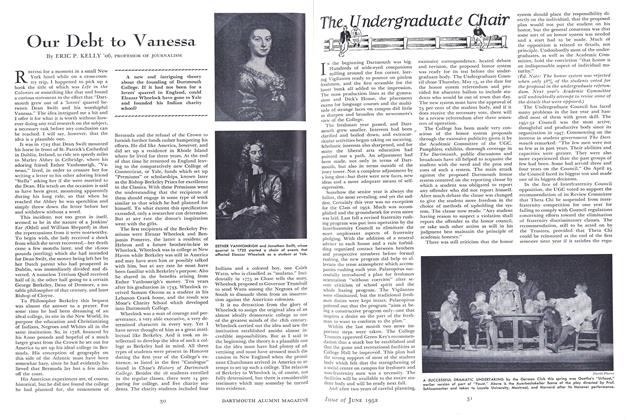

It was in 1723 that Dean Swift mounted his horse in front of St. Patrick's Cathedral in Dublin, Ireland, to ride ten speedy miles to Marley Abbey in Celbridge, where his adoring friend Esther Vanhomrigh, "Vanessa," lived, in order to censure her for writing a letter to his other adoring friend "Stella" asking her if she were married to the Dean. His wrath on the occasion is said to have been great, mounting apparently during his long ride, so that when he reached the Abbey he was speechless and simply threw down the letter before her and withdrew without a word.

This incident, not too great in itself, seemed to be in the nature of a Jenkins' Ear (Odell and William Shepard) in that the repercussions from it were noteworthy. To begin with, the lady received a shock from which she never recovered,—her death came a few months later, and the 16,000 pounds (sterling) which she had intended for Dean Swift, the money being left her by her Dutch parent who had prospered in Dublin, was immediately divided and diverted. A nameless Tertium Quid received half of it, the other half going to a certain George Berkeley, Dean of Dromore, a notable philosopher of that century, and later Bishop of Cloyne.

To Philosopher Berkeley this bequest was almost the answer to a prayer. For some time he had been dreaming of an ideal college, its site in the New World, its purpose the education and Christianizing of Indians, Negroes and Whites all in the same institution. So, in 1728, financed by his 8,000 pounds and hopeful of a much larger grant from the Crown he set out for America to set up his ideal college in Bermuda. His conception of geography on this side of the Atlantic must have been somewhat hazy, since he had evidently believed that Bermuda lay but a few miles off the coast.

His American experiences are, of course, historical, but he did not found the college he had planned for, the remoteness of Bermuda and the refusal of the Crown to furnish further funds rather hampering his efforts. He did like America, however, and did set up a residence in Rhode Island where he lived for three years. At the end of that time he returned to England leaving to the comparatively new College of Connecticut, or Yale, funds which set up "Premiums" or scholarships, known later as the Bishop Berkeley Prizes for excellence in the Classics. With these Premiums went the understanding that the recipients of them should engage in some type of work similar to that which he had planned for himself. To what extent this specification extended, only a researcher can determine. But at any rate the donor's inspiration went with the gifts.

The first recipients of the Berkeley Premiums were Eleazar Wheelock and Benjamin Pomeroy, the latter a resident of Hebron and a future brother-in-law to Wheelock. Wheelock was in college at New Haven while Berkeley was still in America and may have seen him or possibly talked with him, but at any rate he must have been familiar with Berkeley's purpose. Also he shared in the benefits arising from Esther Vanhomrigh's money. Ten years after his graduation in 1733, Wheelock received Samson Occom as a student in his Lebanon Crank home, and the result was Moor's Charity School which developed into Dartmouth College.

Wheelock was a man of courage and perseverance, a very able executive, a very determined character in every way. Yet I have never thought of him as a great intellectual like Berkeley. And it took an intellectual to develop the idea of such a college as Berkeley had in mind. All three types of students were present in Hanover during the first year of the College's existence, as listed in the first "Catalogue" found in Chase's History of DartmouthCollege. Besides the 16 students enrolled in the regular classes, there were 14 preparing for college, and five charity students. The charity students included four Indians and a colored boy, one Caleb Watts, who is classified as "mulatto." Incidentally in 1775 as Chase tells the story, Wheelock proposed to Governor Trumbull to send Watts among the Negroes of the South to dissuade them from an insurrection against the American colonists.

It is no detraction from the glory of Wheelock to assign the original idea of an almost ideally democratic college to one of the greatest minds of the 18 th century. Wheelock carried out the idea and saw the institution established amidst almost incredible impossibilities. But as I said in the beginning; the theory is a plausible one for the idea must have had plenty of advertising and must have aroused much discussion in New England when the prominent Churchman arrived in America to attempt to set up such a college. The relation of Berkeley to Wheelock is, of course, not fully determined, but there is considerable testimony which may someday be turned into evidence.

ESTHER VANHOMRIGH and Jonathan Swift, whose quarrel in 1723 started a chain of events that affected Eleazar Wheelock as a student at Yale.

PROFESSOR OF JOURNALISM

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDeaths

June 1952 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleThe Cold War and Liberal Education To a Father From a Dean

June 1952 By STEARNS MORSE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

June 1952 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1952 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1952 By CONRAD S. CARSTENS '52

ERIC P. KELLY '06

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

July 1953 -

Article

ArticleVOX CLAMANTIS IN DESERTO

December 1924 By Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Article

ArticleExacting Requirements in Science

January 1940 By ERIC P. KELLY '06 -

Books

BooksJOURNALISM AND THE STUDENT PUBLICATION

June 1952 By Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Books

BooksTHE STOLEN SPRUCE.

October 1952 By Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Article

ArticleHe Makes Students Think

December 1939 By HERBERT F. WEST '22, ERIC P. KELLY '06