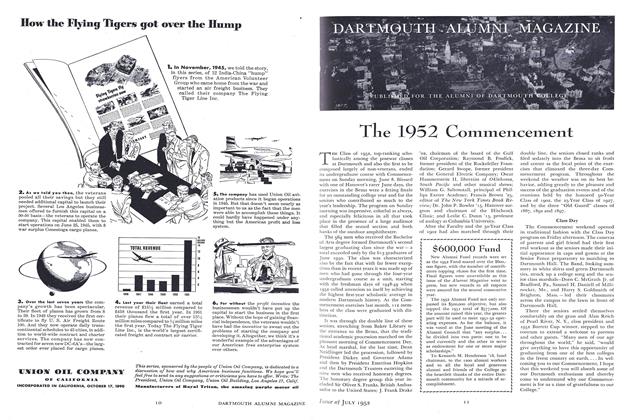

by Prof. John L. Stewart. Prentice-Hall,1952. pp. xxx, 3-645.

It is most pleasant, in this swarming day of the hasty omnibus, assembled by scissors-happy savants and printed by pullulating publishers, to discover a carefully prepared and intelligently organized anthology. It is even more pleasurable to find a gathering of significant literary material, vital, extensive, and yet representative of its genre. Professor Stewart is doubly to be congratulated for his fine collection The Essay: A Critical Anthology.

Mr. Stewart divides his anthology into five parts: a general introduction, three thematic subdivisions of material, and a section of questions on the reading. In 17 pages of packed introduction, he defines the modern essay ("any short, unified work of nonfictional prose having some degree of complexity and dealing with a single subject"), shows how widespread the essay remains, and provides a detailed and illuminating method of analyzing it. In section one ("Facts and Explanations") Professor Stewart presents essays designed to tell what things are and how to use them. In section two ("Interpretations and Evaluations") he brings us essays exploring the social, ethical, and aesthetic values of things. Here, in the deepening plan of the book, one finds A. N. Whitehead's "Science in General Education" and Cleanth Brooks' "What does Poetry Communicate?" With section three ("Literary Art and Creative Imagination") Stewart moves on to the richer yet more complicated literary essay. And now we can observe the fine planning of his text. Having included a factual biography in section one and historical essays in two, he now includes biographical and historical essays essentially "literary" in vocabulary, imagery, complexity, and shaping—such essays as Strachey's "Dr. Arnold" or Allen Tate's "The Death of Stonewall Jackson."

At the end of this great wealth of abundance wisely-chosen comes a section of questions on the reading. Although one may guess that this springs from the publisher's scheming and although one may deplore on principle such an invasion of teaching rights, one must confess that Mr. Stewart's queries are pointed, searching, and provocative, leading the student a full awareness of the style clothing the content.

This is one textbook out of many—one whose wide range should delight the student, whose tough core of reading make him ornament himself in learning, whose high level of commentary should increase his ability to judge and dispose of his intellectual business.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1952 By E. BRADLEE WATSON '02 -

Article

ArticleThe 1952 Commencement

July 1952 -

Article

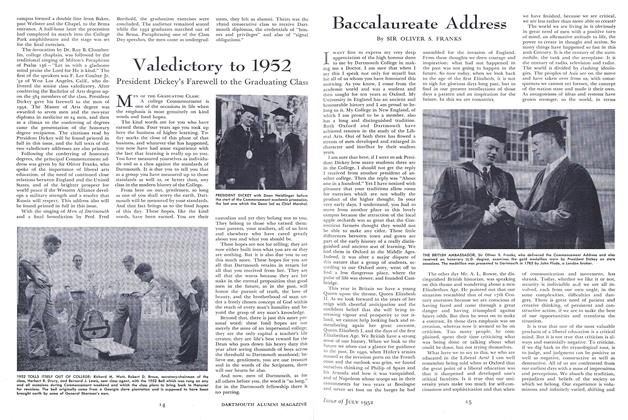

ArticleBaccalaureate Address

July 1952 By SIR OLIVER S. FRANKS -

Article

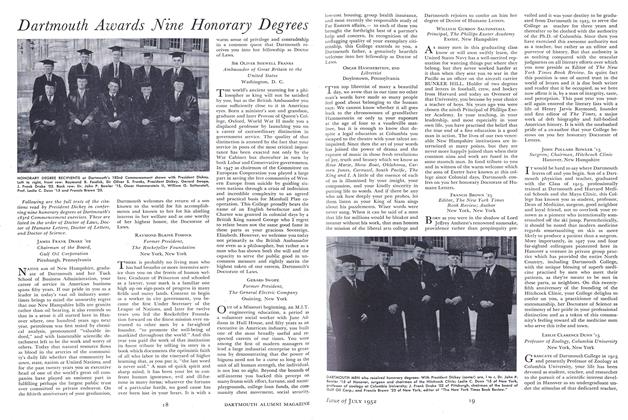

ArticleDartmouth Awards Mine Honorary Degrees

July 1952 -

Class Notes

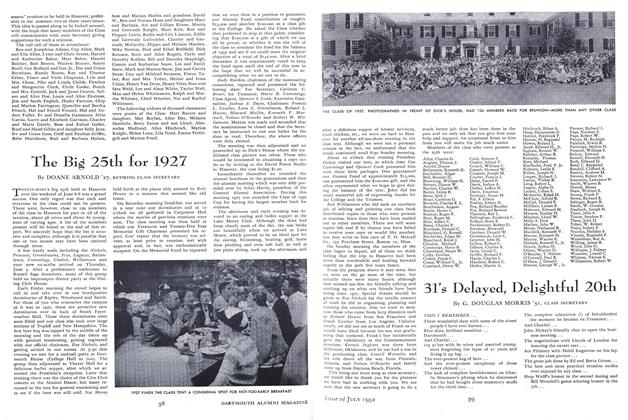

Class NotesThe Big 25th for 1927

July 1952 By DOANE ARNOLD '27 -

Class Notes

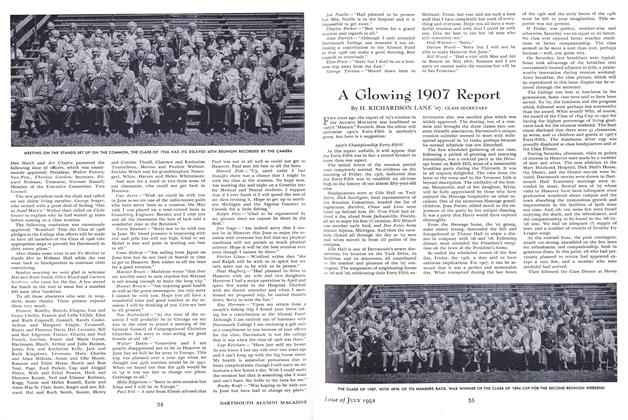

Class NotesA Glowing 190 7 Report

July 1952 By H. RICHARDSON LANE '07

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

July 1920 -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

November, 1924 -

Books

BooksA BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE WORKS OF EUGENE O'NEILL.

NOVEMBER 1931 By Benfield Pressey -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN THE CARIBBEAN.

January 1960 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksPRACTICAL HANDBOOK OF INDUSTRIAL TRAFFIC MANAGEMENT

July 1953 By KARL A. HILL '38 -

Books

BooksTHE GREAT TECHNOLOGY

October 1933 By McQuilkin DE Grange