NEWTON ALVIN FROST came to Hanover in 1871. With him was his young wife Eleanor Louise Frost. Together they opened a small jewelry and watch repairing shop, where she served as his assistant during the earlier years. Mr. Frost sold his business in 1907 to Mr. Carter but retained a desk in the store for his insurance business. For many years he was the Associated Press correspondent for Hanover and vicinity, and in 1924 he became president of the Dartmouth Savings Bank.

A son, Walter Alvin Frost, was born to Mr. and Mrs. Frost in 1875. He died in his 19th year while attending Holderness School. It was the great hope and desire of his parents that he should go through Dartmouth College. Walter was their only child and it was a terrible and bitter blow to lose him just as he was entering young manhood. There are those now living who will remember this boy's picture hanging on the wall behind Mr. Frost's desk, often with a sprig of evergreen on the frame.

But theirs was not a senseless grief. The high hopes for their son found an outlet in their high hopes for youth. Mr. and Mrs. Frost estimated what it would have cost to put their son through Dartmouth. This amount they put aside. They then went to the Dean, Charles F. Emerson, and told him of their fund and its purpose. No one will ever know how many students Dean Emerson sent across the campus to Mr. Frost's office. No one will ever know how much money over the long years he "invested in youth." In the phrase of Prof. L. B. Richardson, "Mr. Frost was a modest man and did not advertise." However this is one of the finest illustrations I have ever known of making an asset out of a liability. Years later he was to say to one of these youths to whom he had loaned money: "The finest thing in my life now is a few of you old boys who remember."

The story of one of these youths is well known to Dartmouth men. This was recently re-told by Trustee Charles J. Zimmerman '23, when he was chairman of the Alumni Fund Committee:

A SMALL DIVIDEND

On a warm spring day in 1885 a young telegraph operator in White River Junction, Ver-Mont, left his instrument and journeyed five miles up the river to Hanover. Once there he sought out the local jeweler, a Mr. N. A. Frost, who kept an open door and an open purse for many a Dartmouth student needing a helping hand.

The young man quickly identified himself and explained that he was eager to attend Dartmouth College, but that his savings and potential earnings would not see him through. "Sir," the young man concluded, "I'd like to ask you to make an investment in me."

The youth's personality and obvious sincerity appealed to Mr. Frost and after but a moment's thought he agreed. Thus started a unique and productive relationship. The young man was Ozora S. Davis '89, later a minister, author, and college president. He distinguished himself as a student at Dartmouth and in graduate work. In his chosen career Davis received many distinctions, but never did he forget the man who had made his success possible. Year after year, as honors came to him, he would send a note to Mr. Frost, recounting what had happened and saying, "Here is another small dividend on your investment."

Another outstanding "investment" was in Lewis Parkhurst, Class of 1878. This was told me by the famous Secretary of his famous class, Mr. William Parkinson. Parkhurst in his junior year was forced by financial conditions to leave college. He had secured a small school in northern New Hampshire for the winter term. He went to see Mr. Frost.

"How much do you need, Mr. Parkhurst?"

"I need fifteen dollars for car fare'! was the reply. Mr. Frost gave him the money and as he was leaving the store asked, "And what have you for a watch, Mr. Parkhurst?" "Oh, I can't afford a watch," was the reply. "But if you are going to teach you must have a watch, Mr. Parkhurst." And Mr. Frost went to his case where several watches were hanging and selected an old American Waltham watch. Many of you, I'm sure, will remember these famous old watches. They were heavy, nearly an inch thick, and good time-keepers under all conditions. This watch Mr. Frost handed to Parkhurst and he set off for his school.

On arrival he found out that the big boys of the school had "thrown out" the two preceding teachers. These were the "good old days" of the ungraded schools, which the big boys of the town attended during the winter term.

Mr. Parkhurst left a vivid description of his first day in that school, and it was told me by his classmate, Mr. Parkinson, Secretary of his class until his death. I'm sure many who read this will recall the remarkable class notes of the Secretary to the 1878 class.

Mr. Parkhurst opened school by reading from the Bible. So far, so good. Then he arose and took off his coat. "I've been hired," said he, "to teach this school. I don't know whether I'm going to or not. But why wait longer to find out? If any of you feel I'm not, let's determine that fact now." Many of you who recall Mr. Parkhurst will remember him as a vigorous specimen of manhood even in his later years.

Three big boys immediately accepted the challenge. Fortunately, the largest of the trio came down the aisle a stride ahead of the others. Parkhurst swung hard and landed a blow flush on the big fellow's chin. Down he went over a desk, temporarily out of the melee. He grabbed the others, one under each arm, worked his way to the door and threw them out into a big snowdrift. By this time the first lad had returned to consciousness and charged again. Parkhurst drew back as he lunged past and then booted him hard from the rear, sending him sprawling into the snow on top of the others. This was the auspicious beginning of what the School Committee reported later was "the best school we ever had at the Corners!"

Mr. Parkhurst became a partner in the large publishing firm of Ginn & Company and later a Life Trustee of Dartmouth College. He gave Parkhurst Hall to the College in memory of his son who died in the First World War. On his retirement from Ginn & Company, the employees gave him a dinner. At this dinner they presented him with a beautiful Hamilton gold watch. When Mr. Parkhurst rose to respond it was evident that he was deeply moved. "Friends," he said, "I want you to know how deeply appreciative I am of your splendid gift." He then told them of another gift of another watch. Then and there he reached into his vest pocket and pulled out Mr. Frost's American Waltham watch. "I have carried Mr. Frost's watch all my life, and I think you will understand and appreciate it when I say I think I shall continue to wear it to the end of the chapter." And he did.

During my senior year at Hanover I found myself in a serious financial difficulty. Before, by working summers as a bellhop, I'd always been able to meet back expenses. Now I was up against it as I could not get my diploma until all outstanding bills were paid. I explained this difficulty to Dean Emerson, and he sent me down to see Mr. Frost. "How much do you want?"

"Sixty dollars, Mr. Frost." He looked me over shrewdly and I've never forgotten his comment: "Well, I think I can trust your honesty but you're so damned skinny that I'm going to ask you to take out an insurance policy with the National Life of Vermont." And this we did.

Many years later Mrs. Frost said to me, "I cannot recall that we ever lost any money, certainly very little, from these loans to the old boys."

I am sure the vintage of college men before the turn of the century will remember the Frost home and the wide grounds around it. After Mr. Frost's death the College Treasurer, Halsey Edgerton, called upon Mrs. Frost. Years later she told me that the interview went as follows:

"Mrs. Frost, if you wish to transfer your house to the College, we in turn will see that you have a nice apartment not too far from the center of things and it will be rent free as long as you live." Then Mrs. Frost, looking up at me with that bright twinkle all her friends knew so well, chuckled and said, "But Mr. Edgerton when he said that didn't know I was going to live to be 100 years old."

Mrs. Frost's flashes of wit and her comments on current situations and personages are well known to all who knew her in these last decades of her long life. I called her one afternoon when I was at the Inn to see if I could drop in for a visit. She was then in her 97th year. "Well, I want to see you, but you can't come this afternoon as the hairdresser is going to be here to give me a permanent."

The last time I saw her she had passed the 100th mark. As I was about to leave she made what seemed to me a very strange request: "Will you walk around my room, sir, and look at what I have here, the pictures on the walls, the books in the cases everything." This I did, a bit self-consciously I admit, and when I came back to her cotside: "Now did you see anything you liked? For if you did, I want you to take it and keep it in remembrance."

When Mr. Frost died in 1926 an appreciation of his life and character was written by Prof. Charles D. Adams. Entitled "Christian Gentleman," it said:

"Mr. Frost spent a long life among us. We shall sorely miss his face and his voice. He had without realizing it made us all his beneficiaries. The characteristic of Mr. Frost which above all gave him this influence was his splendid fidelity. We knew he was trustworthy. He liked to see the hallmark 'Sterling' on his silver; we came to see it in his character. To fidelity Mr. Frost added the companion virtue, generosity. The offices of trust which he held, without financial return to himself, demanded a large share of his time and thought; he gave both gladly and found in such service much of the satisfaction of life. Of his more intimate benefactions and his life was full of those only the recipients knew. These are men and women now widely scattered, who remember the time in their early life when Mr. Frost's generosity and his trust in youth opened to them the closed doors of opportunity."

Mr. and Mrs. Frost's generosity has become a continuing opportunity. Halsey Edgerton, executor of the Frost estate, estimates that the total evaluation of Mr. and Mrs. Frost's gifts to Dartmouth College add up to the magnificent amount of $295,000 "the largest benefaction ever given Dartmouth by a resident of Hanover."

AN APPRECIATIVE LETTER

November 12, 1935

Mrs. N. A. Frost

Hanover, New Hampshire MY DEAR MRS. FROST: I was very much pleased when I called on you Saturday to find you in such excellent health and, if I may use the word, so "chipper."

It is unnecessary for me to tell you how much I thought of your husband and how much he did for me. I was very much pleased to learn what you said about his property going to the College after you have finished with it.

The lady who was calling on you at the same time I was there I think a relative asked me, when she knew that I had retired from business and was a loafer, what my hobby was, and I said Dartmouth College, in New Hampshire.

Trusting this will find you in continued good health. I am, believe me, Sincerely yours,

LEWIS PARKHURST

A LETTER FROM MRS. FROST

November 23, 1950

DEAR MR. HATCH:

Today is Thanksgiving. I have so much for which I should be and am most thankful. Not the least is my appreciation of a friend like you who goes to the trouble of sending me the copy of those most interesting class letters. I assure you I enjoyed each one and wish to thank you for your kindness in thinking of me. I am about as when you saw me on your last visit to Hanover. I had, as you know, my hundred and first birthday last August, at which time I received your lovely card. I wish to thank you for that also. With all these birthdays I can truly say I don't feel a bit older.

I do hope you enjoy a pleasant winter at your Florida home and that you won't pass me by on your next Hanover visit.

Very Sincerely,

ELEANOR L. FROST

While this letter was in the handwriting of her efficient nurse, Elizabeth C. Sullivan of Lebanon Street, her signature was in her own hand.

Mrs. Frost died on Christmas Eve, 1950. Shortly afterward I received a letter from Ernest Bradlee Watson, Professor of Dramatic Literature at Dartmouth.

December 29, 1950 DEAR ROY

I am mailing with this note a copy of this week's Hanover Gazette with a tribute to your dear friend, Eleanor Frost, which her executor asked me to write.

As you perhaps already know, she died at 3:15 a.m. Sunday, December 24, attended only by her faithful nurse, Miss Sullivan. For about a week she had been clearly waning, but up to the day before her death her faculties remained amazingly clear. On Friday she said she wanted to see me, and it was then that she proposed perpetuating her $100 prize for student plays. She called in her financial manager, Mr. Rennie, and gave him necessary authorization to provide an additional $2,000 for the purpose. She also made very clear stipulations as to how the prize should be awarded, and these I have recorded and placed on file with the College Treasurer and the manager of C.O.S.O. I need hardly say that this prize, which she had given regularly for two decades, had been a very great help to me in encouraging dramatic writing among our students.

Daisy and I, like yourself, have long been devoted to her and we shall miss the bright half hour we spent with her whenever we could. Her wit and good spirit were unfailing. When her nurse, a good Catholic, proposed reading a prayer for her the prayer for one near the end her old humor flared up at the words "forgive all my sins," and she interrupted to say, "There's no use in that, I may live to sin some more before I go" she who, I suspect, never so much as thought of sinning in all her life!

This "Investment In Youth" by both Mr. and Mrs. Frost has been most fittingly described by the Psalmist:

"And he shall be like a tree planted by the rivers of water that bringeth forth his fruit in his season; his leaf also shall not wither; and whatsoever he doeth shall

prosper."

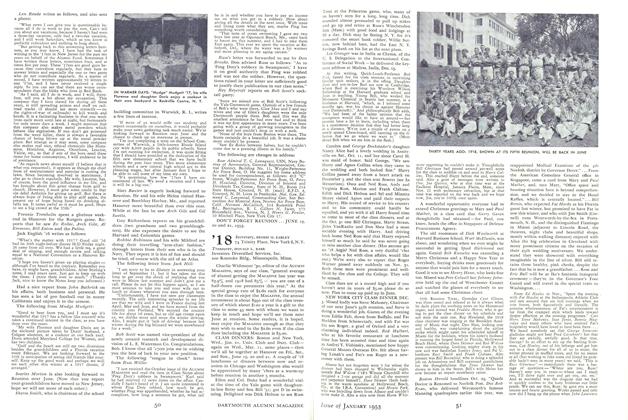

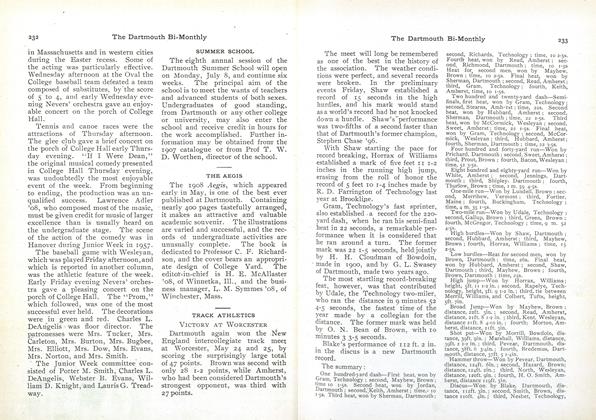

MRS. N. A. FROST ON HER 100TH BIRTHDAY

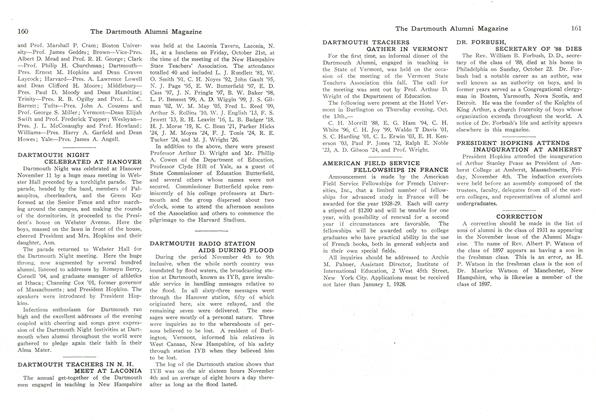

A LIKENESS OF MR. FROST from the oil painting done by his wife about 1935.

The story of Mr. and Mrs. Newton A. Frost of Hanover, "who keptan open door and an open pursefor many a Dartmouth studentneeding a helping hand."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleFAITH and the Dilemma of the Educated Man

January 1953 By FRED BERTHOLD '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

January 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

January 1953 By ENS. SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMOND J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

January 1953 By OSMUN SKINNER, JOHN PHILLIPS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

January 1953 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

January 1953 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND

Article

-

Article

ArticleSUMMER SCHOOL

JUNE, 1907 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH TEACHERS GATHER IN VERMONT

DECEMBER 1927 -

Article

ArticleSample Creates New York Murals

October 1955 -

Article

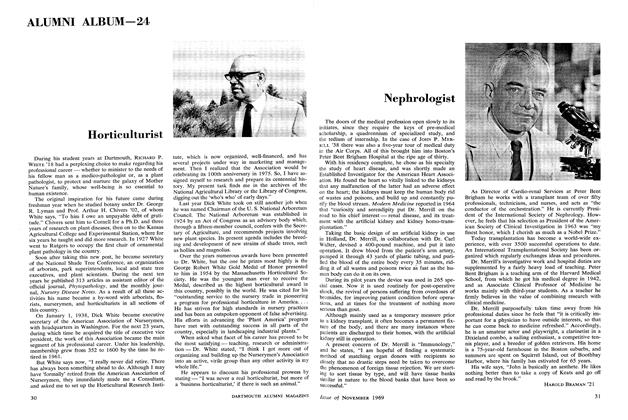

ArticleHorticulturist

NOVEMBER 1969 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Fund Award

JUNE 1973 -

Article

ArticleCalamitous—That's the Word for It

June 1938 By Prof. Donald E. Cobleigh '23