Nathaniel Leverone Professorof Management

To James Brian Quinn, the world of business and industry is a stage where some of the most gripping drama of this civilization is in continuous performance, where many of our most creative per- sonalities are at work. This is not necessarily a fashionable view, but Quinn, a member of the Tuck School faculty since 1957, has little patience with fashion which is at odds with facts as he sees them.

His primary concern is with how the modern partnership of business, technology, and science will meet worldwide needs - how these forces can better satisfy social goals and the material demands of a growing populace. Central to this theme is the high drama of the marketplace, of talented people striving for and against each other to produce needed, or desired, goods and services for a shifting blend of personal gain and public good.

One of Quinn's major concerns as a scholar and as a teacher of future business leaders is entrepreneurship - a scarce but essential commodity in an economic and social system dominated by large, highly structured institutions which tend to prize teamwork and fear the risks and disruptions of true innovation. Almost by definition this involves a focus on the entrepreneurs themselves, the substance of their personalities, their roles in the market economy, the characteristics that drive them to break out of established molds to effect change, to create new opportunities, new markets, new products, new service concepts. "These," Quinn says, "are marvelous people, often tremendous characters who, as individuals, really make a difference - and have great fun at it."

Yet within a corporate framework, the very electric qualities which make entrepreneurs an exciting breed often also make them about as comfortable as an electric shock for colleagues working to keep essential but routine operations running smoothly, profitably. In this context, Quinn is studying ways by which large institutions nevertheless can structure entrepreneurial change from within. "It is hard for the entrepreneur to survive the control systems and social values inevitable m a large institution," he notes. "It is also a strain on the institution to accommodate some of the eccentric qualities of the entrepreneur. Yet the entrepreneur is especially needed within the modern corporation. The trick is how to stimulate entrepreneurship while maintaining the organizational discipline competition requires."

Also an authority on long-range planning and management of technological change, Quinn has, for a decade and a half, been suggesting how leaders of industry, government, and the scientific community can work together systematically to meet the monumental problems he and others who looked could see looming on the horizon. Results were long in coming, but in this country and around the world he finds enlightened business leaders adding important new dimensions to their thinking. Many firms have responded effectively to complex new social issues. Employing minorities, assisting less developed countries, humanizing the work environment, coping with raw material and energy shortages, improving product safety, and decreasing pollution have required significant technological advances and changes in traditional organizational roles.

Quinn stresses that it will require considerable time before many current technological and planning efforts show results, but he feels gratified that scores of young men who have gone through his seminar at Tuck on the management of technological change are now occupying positions having policy impact in both industry and government. Among them, for instance, are Frank Herringer, Tuck '65, who is now Administrator for the Urban Mass Transit Authority of the U.S. Department of Transportation; Ron Johanson, Tuck '65, Vice President of Corning Glass; and Charles Dick, Tuck '72, who is now working with the deputy director of the Federal Office of Management and Budget.

Quinn is critical of society's punitive at- titude toward business in such as areas as environmental improvement and, on the other hand, of business' own ineptitude which fostered that attitude. "Granted," he says, "business did not have a positive stimulus to solve ecological problems until recently, but it should have foreseen the consequences of its actions and - in its own self-interest - gotten on with solutions. Instead, problems of product safety or environmental improvements were often regarded as 'externalities' - they were even called that by economists - hence costs to be avoided rather than legitimate demands to be served. Business waited for government to enforce rules on it. And for the most part government and society tended to seek a scapegoat, someone at fault, when ecological damage ultimately became intolerable. They then sought someone to 'punish' to end the perceived insult. And business regarded regulation as punishment. What we are really looking at now - and what business and government should recognize them for - are changes in social demands. Demands for clean air and water are at the core not that much different from any other demands, if you see them that way.

"Similarly, on a larger social scale, when we had a public demand for sewage systems, when we decided open trench sewage was not only unpleasant but a menace to public health, we developed a whole market for sewage disposal facilities, and a major industry grew up to meet that social need. New companies and jobs were created, and we are all better off. This was not a social cost, but a new demand. Today we have the same kind of problem, if somewhat more complex. We want to breathe clean air and keep our rivers and lakes pleasantly free of modern filth. These demands, too, can lead to a multiplicity of opportunities - jobs, products, and services - to solve these problems. But we need to see them as demands and challenges in a new public marketplace, not as 'costs' we can avoid by ignoring them."

A vein of optimism runs through Quinn's views: "By the year 2010 people will look back on the years 1970-1975 and wonder what the flap was all about. By then, looking back, it will seem obvious that one couldn't continue to dump lethal chemicals into rivers or into the air. People will wonder why we ever put up with such things, just as today we wonder why people in the Middle Ages put up with the practice of everyone dumping slop buckets out the window into the open street.

"These changes will involve shifts in thinking about how one defines the cost of production of a product, or the cost of doing business. However, as we recognize that industry should no longer arbitrarily throw part of its cost onto society, it will be essential to make sure that the same rules apply to all, that some businesses are not punished by regulations while others are rewarded for irresponsibility."

Quinn was graduated from Yale in 1949 with a B.S. in engineering, earned an M.B.A. at Harvard Business School in 1951, and received a Ph.D. in economics from Columbia in 1958, a year after he joined the Tuck School faculty at Dartmouth. He has been a consultant to several American and foreign corporations and to several federal agencies. He assisted in developing approaches to long-range planning of technological change for Norway and Colombia, and has studied science policy and the impact of multinational companies in France, Britain, Sweden, and Australia, where he spent much of last year on a Fulbright grant. He is author of Yardsticks for Industrial Research.

The professorship, designed to encourage initiatives in teaching and research, was established in 1973 in memory of Nathaniel Leverone 'O6, an entrepreneur in his own right as founder of the Automatic Canteen Company. It was endowed from part of the bequest left to Dartmouth by his widow, the late Martha Ericsson Leverone.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth De Gustibus: More Food for Thought

December 1974 By JOAN L. HIER -

Feature

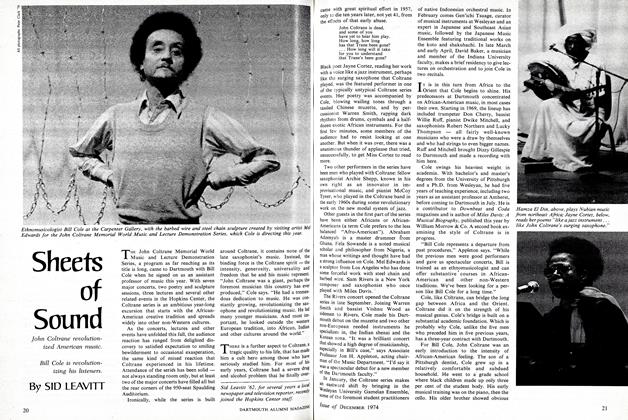

FeatureSheets of Sound

December 1974 By SID LEAVITT -

Feature

FeatureChartres in a Chevrolet

December 1974 By ROBERT L. McGRATH -

Feature

FeatureOur Crowd

December 1974 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

December 1974 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

December 1974 By PAUL WOODBERRY, CHARLES S. KILNER

R.B.G.

-

Article

ArticleIt's Still "Men of Dartmouth"

NOVEMBER 1972 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleEndowed Professorships

MARCH 1973 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleGORDON J.F. MACDONALD

October 1973 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleS. MARSH TENNEY

May 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleLAWRENCE E. HARVEY

January 1975 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleBenjamin Ames Kimball Professor of Administration

March 1975 By R.B.G.

Article

-

Article

ArticleTIP TOP HOUSE ON MOUNT MOOSILAUKE

January 1921 -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

May 1943 -

Article

ArticleThe Fighting Hinmans

April 1944 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Meets

JUNE 1983 -

Article

ArticleSONNET TO MOST MODERN POETS

NOVEMBER 1931 By A. Kahn, Arts Quarterly -

Article

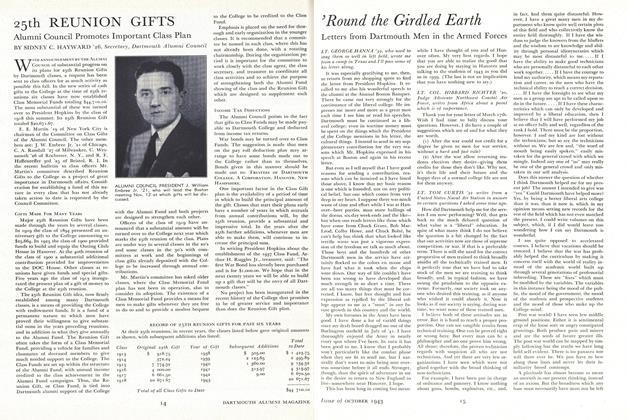

Article25th REUNION GIFTS

October 1943 By SIDNEY C. HAYWARD '26