SOME time ago I ran across a cartoon which showed a man, obviously a long-haired intellectual, standing in a fashionable gallery, looking at a picture and saying, "I know everything about Art, but I don't know what I like." This cartoon illustrated the dilemma which is characteristic of the modern, educated man. Typically it has been his desire to "know everything," and typically, too, it has been his lot to feel increasingly ill-at-ease in the face of problems of value. To "know everything" has meant to know all the "hard facts." But somehow this knowledge has not enabled the educated man to solve problems of better and worse. Increasing "objective knowledge" has not brought with it an increasing sense of the larger significance for human life of the fruits of knowledge. The hope that, if we could only collect enough facts, the proper value standards would somehow emerge this fondly cherished hope has been frustrated. And yet there remains in our educational institutions a bias in favor of "hard facts" and a suspicion of "subjective values."

To be sure, it is much easier to live with hard facts than it is to live with our likes and dislikes. The hard facts have something democratic about them; they are there, they look us straight in the eye, and they play no favorites. They are the fruit of our favorite industry, science, and they seem to justify our reliance upon the intellect. On the other hand, our likes and dislikes seem to be mysteriously private, to erect barriers between man and man, to create misunderstandings and difficulties. Our lives in the realm of values seem resistant to the dispassionate voice of reason.

If I were to say, for example, that phosphorous burns at a lower temperature than carbon under the same conditions, I presume that most of you would agree with me. Even if you disagreed on the matter of fact, you would no doubt agree on a certain method by which we might check up on the statement. But if I should make the assertion that the greatest modern poet is Eddie Guest, I should expect at least some of you to disagree. Or if I should assert that our best hope for good government

and a sound foreign policy was defeated when Governor Stevenson was defeated, some would no doubt cheer loudly while others would "hiss." The difficulty here is not only that we disagree on these evaluations, but more than likely we are hopelessly disagreed on what method we might use to settle them.

To get an education in our day has meant, by and large, to seek to reduce life to facts, to rip away the veil of mystery from one area after another until we get to some bedrock truth upon which all men can agree. The generative idea of our time and of our civilization has been science, and science has meant "objectivity." We have, of course, been aware that certain basic value standards are necessary for the cohesion of any community. But we have felt that it is not intelligent to accept these standards arbitrarily and that they are, indeed, arbitrary unless grounded in objective fact. Perhaps the most damning phrase that can cross the lips of the educated man is, "That's just your opinion." Allegiance to a set of values has a taint of unrespectability unless those values can be proven to the impartial judge.

Yet, I believe, it is precisely one of these hard, objective facts that in the course of our pursuit of "objectivity" something fundamental has gone wrong in our total life as human beings. We have become increasingly alienated from ourselves as responsible, valuing beings. That dimension of our existence which is most indispensable to our full stature as human beings has become increasingly problematical to us. There is a modern philosophy which goes by the name of "logical positivism," a philosophy symptomatic of our times. One wit has said that, according to logical positivism, "The knowable is unimportant, and the important is unknowable."

SHORTLY after the atom bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, the atomic physicists became quite excited about the moral issues involved. In the Bulletin ofthe Atomic Scientists there were long communications back and forth. One man, a prominent figure in research, raised the question as to whether he and his colleagues ought not to refuse to do any further work on atomic fission, since it could evidently be put to such horrible uses. I remember discussing this question with a scientist friend of mine. He said something like this: "It's awfully presumptuous of that fellow to set his moral sense over against that of the vast majority of his community." Then he went on to make the further point: "If it were a matter of scientific fact, he would have to report his conclusions no matter how unpopular they might be. But in a case of moral opinion one has nothing solid to go on. It's all a matter of opinion."

This apparent gulf between facts and values is reflected in various ways in our educational institutions. On this campus, for example, we still have courses which quite openly deal with values, aesthetic, moral and religious. They manage somehow to "go ahead" despite the fact that they are unable to demonstrate how these values flow from some necessary law inherent in the objective facts. And yet there are many people who are uncomfortable at this lack of objectivity. The editor of The New Yorker reported some time ago that he had received in the mail a little contrivance called "A Reading-ease Calculator." The genius of this device was that you could apply it to any given bit of reading matter to find out if it was any good, eliminating all subjective judgment and, presumably, also eliminating the need for highly trained and well-paid editors such as the gentleman who reported this in The New Yorker. All you had to do to operate this calculator was to set a little dial according to certain instructions, twirl an indicator, and read the verdict which was delivered in one of four categories: very hard, hard, easy, very easy. The book of instructions informed one that this also constituted a rating of the excellence of the material: the easier the better. Our editor reported that his first application of the device was to the book of instructions which accompanied it. It rated "very hard," and, in this case at least, he was inclined to agree.

As far as I know, no one on our campus has been driven quite so far as that by the desire to put value problems "on a good, sound basis." Yet a yearning in this direction is not altogether absent. I can personally testify that a good many students in our courses in religion are frustrated because the last lecture does not come out with THE ANSWER. Some seem to feel that, if I could only recommend the "right book" or tell them just the pertinent facts, they would be able to decide: this faith or that faith or no faith. Some feel that the failure to provide factual and objective answers reduces many courses to the level of second-rate intellectual food. True, many of these "value courses" still do have considerable prestige and manage to attract their share of the better students. And yet there is a general tendency to regard them as valuable chiefly for the "polish" or "general background" that they are thought to provide. They are luxury items. They do not, we are told, "dig any potatoes." They are rather nice for "cultured conversation" (whatever that may be!), but they don't put us forward in the real business of life.

The other day I was talking with a friend on the medical staff of the Hitchcock Clinic. He was enthusiastic about the seminars that are constantly held among the staff members. They get together to work on common problems, to share information, to work out new theoretical conceptions. There is real life there, a concern to push back the borders of ignorance and an optimism in the undertaking. It seems to me, on the other hand, that a sense of isolation is the fate of the man who works in what we call "the humanities." There are individual men there concerned with problems of value, but thereseems to be no effective forum of concern, nor much hope that such a thing might be created. This is a very hard thing for a liberal arts college to have to admit: the real collegium, the real community of concern, seems to be found not in the humanities but in the sciences. Some people are becoming so disturbed by this that they are willing to take radical steps to correct it. "Let's all read the same 100 great books," they say, "and then we'll have something to talk about." Well, perhaps even that is better than the extreme fragmentation which we now have.

Those who seek to work with problems of value are often beset by a feeling of inferiority. The high aim of our calling is not matched by achievement. We argue that men cannot form a community except around shared values, but our discussions seem only to accentuate our differences. The upshot is that, in our discouragement, we find it easier to turn away from the problem of end-values. We can be effectively concerned with the question "How do things work?" But we are frustrated and divided on the supreme question of life, "What kind of a person is it worth- while for me to become, and what is worthy of my devoted service?"

WHEN I was a student here at Dartmouth some years ago, I fell one time into a reflective mood. An allegory came to me, an allegory of my own education at Dartmouth. In this allegory I perceived a group of workmen who were working on a vast block of granite. Each had his own tools. And they worked for days and days. Each day, when the lunch hour came, they would stop working and come to a common place to eat. As they ate, they would discuss their work. "I've just discovered a new kind of stroke." "Here's a new way to sharpen the chisel." And so on. Then they would go back to their work. Finally, the time came when someone shouted, "It is finished." The workmen withdrew to a distance to see the result. A look of bewilderment came over their faces. The block of granite had more faces than anything Picasso had ever dreamed of. They finally decided that it was (possibly) interesting, but no one would venture to say just what it was. Now, the allegory is obvious enough, I was the block of granite. And the faculty were the workmen. Each of them had striven to give expression to his ideas, and many were good ideas. But there had been no controlling idea, no unifying conception of the end to be sought.

We could set all of this in an historical perspective. We could say that the genius of our modern culture is to be seen merging in that moment when men of science were able to free themselves from questions of "Why" and to ask the question, "How?" With the rise of modern science we got the vision of impersonal law governing everything in the whole of nature. To use the distinction of Dr. Abraham Heschel, we became preoccupied with the realm of "space" to the neglect of the realm of "time." We sought to penetrate and subdue the realm of "things" and innored the question of human destiny. The vision of an impersonal law of nature grew into a vision of such a law including also human nature. It was felt that, just as Newton had discovered the laws of matter, so other men could discover the laws that govern society and human life. This is not the place to try to tell the whole story of how skepticism gradually ate into this latter hope. But it does seem to be the case that in our day we are not so sanguine about a "science of man." At the same time the science of nature has gone from glory to greater glory. In the midst of vaster and vaster things, the spirit of man has cowered, unable to answer the question, "Who am I?" All of this has contributed to making modern man "anonymous."

A good symbol of this is Willie in Arthur Miller's The Death of a Salesman. Here we have a man who allows himself to be defined as a person by his function in an impersonal system. And when it comes to the point where he can no longer perform that function, can no longer meet the demands of the system, he feels that he has become nothing. As one person in the play puts it, "The poor man just didn't know who he was."

In his recent book, The Lonely Crowd, David Riesman tells us, "Our era is the era of other-directedness, where men are directed by forces outside themselves." This is also one of the central themes of Erich Fromm's book, Man for Himself. Fromm describes the typical modern man as the "marketing personality," the person who defines his status and determines his worth in terms of his function in an impartial economic system. Not only individuals but institutions stand in danger of taking on a "marketing personality." Thus, the college is tempted to make everything else secondary to the purpose of vocational preparedness.

The vision of an impartial law has borne tremendous fruit. It has been one of the genuine achievements of modern man. But what I am trying to point out is that the attempt to spread this vision into the realm of values has failed. Starting with what we believed to be "brute facts" untainted by any personal evalution, we have not been able to win through to any conception of the good for man which could become the basis for a community of the spirit. Men were given hope by the successes of the natural sciences, hope that they could create a rational community of values without falling back upon authority and revelation. Stirred by this hope, they had the strength to overthrow outmoded systems of value and the various authoritarianisms of the Church and the State. But once freed from these older authorities, they have not been able to realize their new hope, and men have been drifting with no new sense of direction to replace the old.

One result of the contemporary sense of futility in value questions is that we are subjected to what might be called "the tyranny of the present moment." One of the objectives of a truly liberal education is to acquaint us with those values which have been able to give various cultures their generative drive down through the ages, to confront us with the best that has been thought and believed so that our own ideals do not grow small. But if we ever get to the point where we feel that these values are merely relative to personal o cultural bias, we cannot really take them seriously at all. Instead of perspective in history we get merely a confusion of voices. One tragic consequence of such relativism is that we have no standpoint from which to criticize whatever values happen to enjoy favor at the moment, whatever opinions happen to be backed with power at a given time. The background for the victory of new totalitarianisms is an ideological vacuum. Wherever people merely accept "what is" because they have no hope that there is an "ought-to-be," there is fertile soil for the frenzied worship of power.

In the modern tragedy we seem to have a very dark kind of stage; and we seem to have a chorus in the background, something like the ancient Greek chorus. Throughout the drama the chorus seems to chant, "Come weal or come woe, my

status is quo."

WELL, supposing that the modern, educated man does find himself in some such dilemma as we have been describing. How has this come about and how can we begin to find a way out? In the space that remains I should like to present this proposition: the original attempt to separate "brute fact" from a context of value was misguided or, to put it in another way, there is no such thing as a significant fact apart from a value context. I should prefer to use a word more congenial to my own way of thinking and say that there is no significant fact apart from faith. For "faith" is a value context or orientation in dynamic operation. The attempt to live without faith has led to the dilemma that we stand in need of a vision of the good and are, at the same time, frustrated because we cannot find one "objectively."

First of all, I should like to say what faith is not. It is not what the Sunday School boy replied when he was asked for his definition. He said, "Faith is believing what you know ain't so." As a matter of fact, faith is not merely a matter of intellectual assent at all. It is rather the commitment of one's total self mind, heart, and soul to what one believes to be of supreme value, of ultimate concern. Faith is the response of one's total being to something held to be of ultimate worth. We might call it the "belief-ful participation in" what one conceives to be of supreme value. There is no significant fact apart from faith.

I am not trying to deny, for example, that we can find in the natural sciences a technique by which we can relatively free ourselves from faith, that we can for special purposes and by special methods and controls determine certain objective facts. Thus, there is no Christian or Muslim law of the pressure of gases. The relative objectivity of science is one of its greatest assets. Indeed, this very objectivity can render a great service to faith: namely, to help purge it of superstition. Faith is necessary to life, but it is also notoriously open to various distortions and perversions. If faith is genuine, it is the commitment of the mind as well as the rest of the self, and it is eager to penetrate to truth and not to be fooled by illusions. Genuine faith is dedicated to the discovery of truth where-ever it may lie. If science is able to show that something we had held by faith is actually not the case, faith should welcome this disillusionment. Freed from illusory accretions, faith is better able to point us to its proper object.

But the point I wish to stress lies in a somewhat different direction. The belief that science is able to eliminate faith from life is, itself, a superstition. Not only does science become significant for life only as it is embodied in a living faith, but the "scientific spirit" itself rests upon an implicit faith.

I drop two objects. They strike the floor at the same time. I record this fact. But unless this fact is incorporated into a broader vision of the world, it remains sterile and insignificant. Now I pick up these same two objects and note that one of them is a solid, heavy object and the other a rather light, spongy object. How is it that they fall at the same speed? As far as I am concerned with the bare fact, it is insignificant. But as soon as I assert that this fact has significance for all of nature, that I am here witnessing an instance of a universal law, something of profound import has taken place. When I go on to say that this fact means that very diverse things in nature operate according to the same laws, that these can be mathematically stated, and further that all of nature is a vast book written, so to speak, in the language of mathematics, I have entered into a new and revolutionary world view. This was in essence the story of Galileo's work. From a few carefully controlled experiments in the laboratory he dared to extrapolate far beyond anything he had evidence for at the moment. He made a venture of faith which was validated later by painstaking effort. He uttered a prophecy, one might almost say, which led many to see facts in a new light and which gave a new significance to life as a whole. It also determined to a large extent what facts future generations would regard as relevant.

But one might argue, "True, men of science in the past had to make a venture of faith. But the future holds a different possibility: namely, that the domain of scientific knowledge may be so extended that faith is no longer needed at all. For then we will, at least in principle, know all of the basic laws governing every event whatsoever." Perhaps something like this may come to pass. I do not myself believe it. But what I should like to point out is that those who do believe it do so, as of this date, as a matter of faith.

WE must live by a faith which gives significance and purpose to our collection of facts. I should like to suggest two reasons why this is so. In the first place, you and I are creatures living in time. We are not eternal, but we come and go. The objective of science is to make time irrelevant to any fact, that is, to extract a law of the phenomena which will hold for any time. Nature is uniform, and real time has no relevance to the formulae of physics. But the things that most concern you and me are relevant to time. You and I must live by faith because we must often decide now, in this unique time and novel situation. Even if we could theoretically know all that is relevant to this moment in which we must decide, the knowledge would come only after the moment had passed.

There is a famous illustration of this in William James' essay, "The Will to Believe." He pictures a man standing on a mountain pass. Suddenly a blizzard comes upon him and he is caught there. He knows that if he stays on the pass he will freeze to death. He also knows that the path down is tricky, that he may very likely miss it in the swirling snow. What is he going to do? He may say, "It would be foolish of me to try to go down, for I don't know for sure where the path is. On the other hand, if I refuse to try I am lost." This man faces a forced and momentous option. For one in such a position to say, "It is unintelligent to act in such an important matter before all aspects of the situation are objectively known" is itself a most unintelligent and unrealistic judgment. Not to decide is a momentous decision.

There is another reason why people must live by faith. There are some things, the most important things I should say, that can be known only as one participates in them. This is true, for example, of those things in the realm of ideals which men are still struggling to embody in the realm of reality. We have all given considerable thought to the question of what democracy is. And yet if we were each asked for our definition, I suspect that each of us would come up with something different. It would hardly be expected that we would all point to a standard set of facts as those relevant to our definitions. For the plain fact is that, considered "objectively," it is very problematical what democracy is or whether we have it. Certainly there are facts about our social order which might lead any of us to say, "But that isn't what I mean by democracy!" We would likely continue, "What I mean is..." and proceed to describe not what is the case but what we could wish were the case. The democracy in which you and I believe is only in part a present fact; it is perhaps even more a vision of what ought to be, a vision which will "come true".only to the extent that we commit ourselves to it wholly. Democracy needs our belief-ful participation in order to become what it ought to be. Again quoting William James, "Faith in a fact is sometimes necessary to create that fact."

In the realm of religion, too, we can know only as we participate. This is true for a somewhat different reason, namely, that the "object" that we seek to know is a profoundly personal Being. God is not an objective fact among other facts that might be known by theoretical deduction or by disinterested observation. He can be known only as we involve ourselves in personal relations with Him. God can be known only as we open ourselves to listen, to receive something.

If these words are unfamiliar to you, think of what is necessary for you to come to know a friend. If you are really going to have this person as your friend, you must act as a friend to him before you can ever know him as a friend. You must give yourself in trust to him before he will ever reveal to you what he is like in his innermost being. In any interpersonal relationship there is an act of faith or trust wherein we give ourselves as the precondition of coming to know the other self. The thing which I am arguing against is a kind of "spectator attitude," the attitude that we should sit on the sidelines and observe life before living it. Is this not a kind of death-urge, this ideal of arrestting the movement of life by objectifying it before one dares to enter it?

An analogy comes to mind here. Galileo argued that there were satellites moving around the planet Jupiter. The professors at the University of Padua refused to look through Galileo's telescope in which, he said, they could see for themselves. But they felt no need to look. They knew the answer already; they had read Aristotle. This both amused and infuriated Galileo. It was the judgment of an area of life from outside by people who refused to participate in what was before them. Today the refusal to look through the telescope occurs rarely in the realm of science. But there are many today who refuse to look at that side of man's life that has to do with values, who, in short, seek to judge from outside without participation.

Before you and I can significantly know this thing we call democracy, we must participate in the community that is struggling for its existence. Before you and I can significantly know beauty in art, we must become participants and, as best we can, creators with those who work in art. Above all, I am convinced, it is tremendously important for us to reclaim our heritage in the realm of religious faith, to become participants in those communities of the faithful within our culture. It is there that men have opened themselves to the experience of that God of Whom the Psalmist says, "For with Thee is the fountain of life; in Thy light shall we see light."

WITH Dartmouth men entitled to some of the bows for its remarkable success, Victory atSea, a pioneer project in historical television, began a 2 6-week run on the NBC network October 26. It is winning praise for the imaginative planning of its producers and the dramatic excellence of its story of the sea, and of the men who fought on, above and under four oceans during the crucial years between 1939 and 1952. Its message on the use of sea power during modern war, transmitted on a scale never before attempted on television, serves as a forceful example of the educational potential of television.

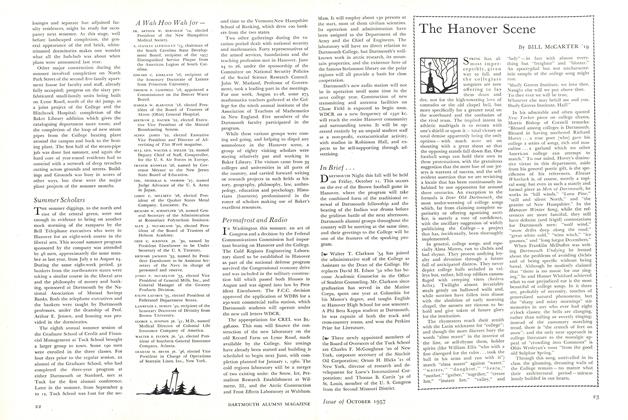

The idea behind the televising of Victory at Sea is attributed to Henry Salomon, naval historian who for more than two years had in mind a plan for presenting a history of naval operations on TV. Salomon approached Robert W. Sarn off, then director of NBC Unit Production and now Vice President in charge of NBC TV's Film Division, who saw in the project a vast opportunity for public service on the part of the network. Sarnoff's conviction was shared by Sylvester (Pat) Weaver Jr. '30, NBC Vice President in charge of Radio and TV, who with Sarnoff and Salomon cleared the decks for complete Navy cooperation and made Salomon writer-producer in charge of the project.

Two other Dartmouth men were instrumental in bringing about the outstanding technical qualities of the production. Donald B. Hyatt '50, who has been associated with it from the beginning, first served as assistant producer under Salomon. Hyatt has recently been named Unit Manager, responsible for business and production matters, in charge of the Victory at Sea staff of twenty. Stanton M. Osgood '30, Manager of Film Production and Theatre Television for NBC, served with Weaver on the NBC-Navy Television Project Committee. In order to produce and coordinate the 26 episodes, NBC had to set up a special unit, since, unlike other historical attempts on television, this one could not be completed by linking together a run of news films.

The production had the enthusiastic cooperation of the U. S. Navy as well as the Marines, Army, Air Force and Coast Guard, and the Navies of our Allies. At a cost approximating one million dollars, NBC is making what is really a movie 13 hours long, out of 50 million feet of official film from ten different governments and 26 government agencies all over the world. Much of the film had been classified confidential and never before seen by the public.

In this country, Victory at Sea is being televised over some fifty stations, reaching potentially the 48 million people who make up the NBC audience, on Sundays, from 3 to 3:30 P.M. It is being shown over some individual stations at other times.

The original musical score is the work of Richard Rodgers, who wrote the music for South Pacific and TheKing and I. It ranges in mood from the soft tropical security of the day before Pearl Harbor to the chaotic suspense of the battle scenes. As there are few gun-shot effects in the series, the music carries a major responsibility for the dramatic impact. A two-hour condensation of Rodgers' music will be recorded later by RCA Victor. A pictorial book of scenes is also being planned.

Victory at Sea has aroused interest also in England, where the television presentations began on October 27. Don Hyatt joined Mr. Salomon in London in September 1951, when they spent a month working with the British Admiralty, obtaining some invaluable film from the Royal Navy. Winston Churchill was among the first to ask to see previews of Victory at Sea. Hyatt's work throughout has involved a variety of responsibilities, among them timing the music for individual episodes, screening film and ordering film footage, and keeping in close contact with Salomon and others in charge of the sustained dramatic concept of the whole undertaking.

The series began in October with an episode entitled "Design for War," showing the tense days following September 1939, when U-Boats "wolfpacked" convoys on the Atlantic. This is accomplished through authentic films, some of them captured from the Germans. Perhaps one of the most effective episodes is the second, entitled "The Pacific Boils Over." Here the story of the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor is seen largely through the eyes of the enemy, as revealed in their own films of the actual combat.

A description of anti-submarine warfare in the Atlantic is followed by "Midway is East," the showing of the Battle of Midway, which strikingly epitomizes its treachery, and our neardefeat and final victory in the sea-fighting against the Japanese.

In the Mediterranean there is the long ordeal of the British, fighting for Malta and the Suez. Guadalcanal, the Solomons, the Philippines, North Africa, and the destruction of the German raider Atlantis are combat scenes well portrayed. The British Commando raids in Norway and an overall picture of the Normandy invasion on "D-Day" mark the halfway point in the series. With the "Fate of Europe" the destruction of the Axis forces in Europe seals Germany's doom. The conclusion of the war with Japan, with the dropping of the first atomic bomb, is the subject of the last episode, under the title, "Design for Peace." With this portentous ending, the repair work of peace begins.

Edmund Leamy in his column in the World-Telegram and Sun writes of this conclusion of Victory at Sea: "The last sight cheers you. You need to be cheered because the memory of those hate-filled eyes stays with you. It stays with you, for you know that today in the eyes of other men that same implacable hatred for us burns, and the mills of the gods are grinding maybe faster than we think."

PROF. FRED BERTHOLD '45 IN HIS BAKER LIBRARY STUDY

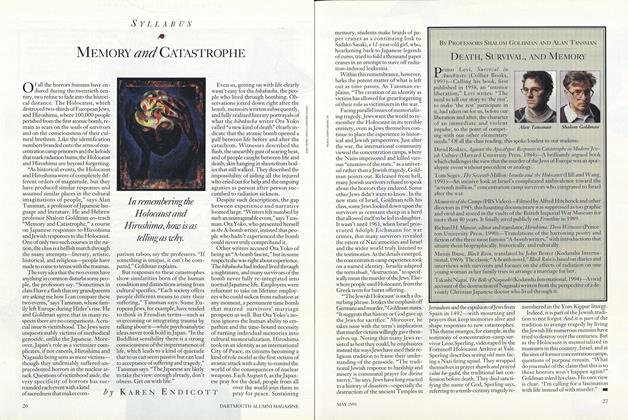

DECEMBER CAMPUS SCENE: SNOW DECORATES THE COLLEGE CHRISTMAS TREE

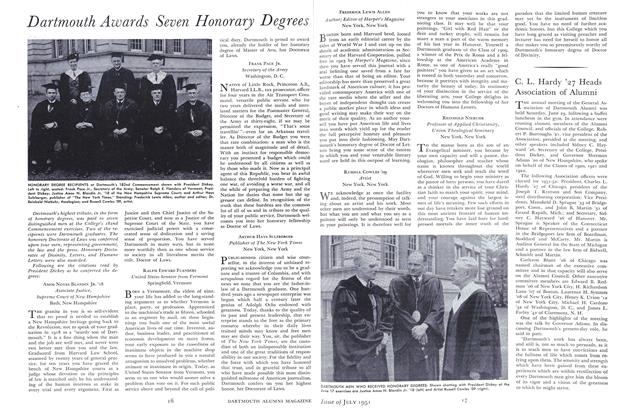

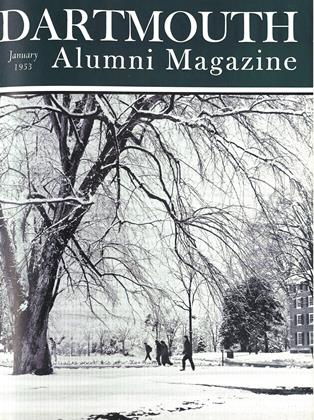

DONALD B. HYATT '50, who first as Assistant Producer and now as Unit Manager has had an important part in the making of "Victory at Sea.

AMPHIBIOUS OPERATIONS

ANTI-SUBMARINE WARFARE

THE CARRIERS STRIKE

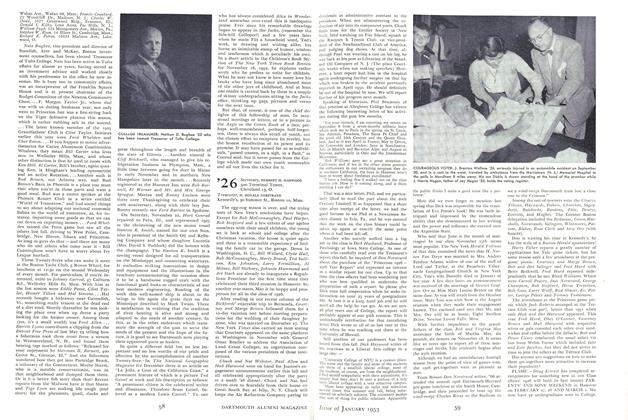

OVER 50 MILLION FEET OF OFFICIAL FILM has been edited in the creation of "Victory at Sea" Above, Don Hyatt hands down two of the reels to Henry Salomon, the naval historian who wrote and produced the 26-week series that has set an educational standard for television.

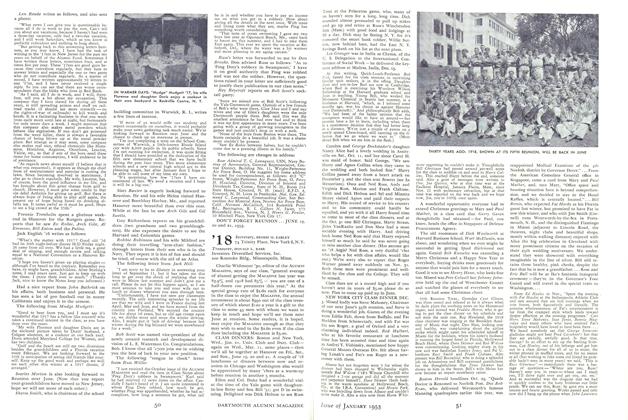

SYLVESTER (PAT) WEAVER JR. '30 (second from left), NBC vice president in charge of television and radio networks, with Secretary of the Navy Dan Kimball (center) and NBC and "Victory at Sea" officials Henry Salomon, Edward D. Madden and Robert SarnofF.

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF RELIGION

About the Author Professor Berthold, who was a Rufus Choate and Phi Beta Kappa scholar as an undergraduate, graduated from Dartmouth with the Class of 1945. He went to the University of Chicago to study for the Bachelor of Divinity degree, which he received in 1947. The year following he took further graduate work at Columbia University, and during 1948-49 taught on the faculty of Utica College of Syracuse University, Utica, N. Y., as Instructor in Philosophy. Although he has remained in the field of teaching, Professor Berthold was ordained a minister in the Plymouth Congregational Church in Utica in 1949. He earlier served as minister of the United Church of Chelsea, Vt. A member of the Dartmouth faculty since 1949, Professor Berthold was made Assistant Professor of Religion in 1951. He is the author of several articles on subjects dealing with religion and psychology. Among other honors for outstanding scholarship, he was a Fellow on the Blatchford Foundation from Chicago Theological Seminary, University of Chicago.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

January 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleAn Investment In Young Men

January 1953 By ROY W. HATCH 02 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

January 1953 By ENS. SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMOND J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

January 1953 By OSMUN SKINNER, JOHN PHILLIPS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

January 1953 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

January 1953 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND