president Dickey, in his address openingthe 185th year, talks about "maturity as thatultimate self-discipline which rules a free man"

MEN OF THE COLLEGE: The excitement of any start is one of the good moments of life. The spirit of the College as a living institution is quickened at Convocation with that excitement. It touches most of us at least momentarily with that high mood of "doing it better" this time. It lightens the burden of the years for the senior; at floodtide for the freshman, it will bear the Class of 1957 over the fervent perversities inflicted on them by the most recent converts to "sophomorics"; and most wonderfully of all, perhaps, it annually gives the good teacher fresh faith in the ancient mystery of learning.

But it is not my purpose today to labor the glories of the perennial fresh starts which seem to characterize the life of a college. Rather, I think I can more usefully urge you to begin to be on your guard against regarding the schoolroom pattern of measured terms and courses as having any marked resemblance to the flow of affairs on the lower reaches of the river down which you are bound. The adventurer into intellectual realms today has usually known the utility of courses and textbooks as starting points, but if he has it in him to go forward on his own, he soon earns the right to know that in the largest sense even the best course is little more than two arbitrary points of beginning and pausing, bounding a teacher's selections from the sea of reality around us.

Parenthetically, I should say that I do not make this observation because I fear it will escape you later in life, but simply because I want to try at the opening of this college year to help you begin to visualize the longer-range targets of a liberating education, targets which naturally enough are still over the horizon of your experience.

The point is that the further you go and the wider your range, both here and later, the fewer clean-cut beginnings you encounter. Anything worth serious thought often seems to involve complexities beyond the very bounds of human bothering and everything of any consequence is found fastened at one end to the past and at the other end to the future. Each day one starts from where he is and lives with the woe expressed to me by a student who remarked that the only trouble with facts is that there are too many of them. Once begun, thinking, like woman's work, is never done.

There is an old reliable remedy for this sort of misery. It is a prescription summed up by the injunction to "let your mind alone" and its popularity is attested by the fact that, whatever other troubles we've known, most of us are mostly at our intellectual ease. But I take it we are agreed that Dartmouth was not founded and built strong as a spa for taking that particular cure.

We are gathered together here as a community of teachers and students, some three thousand strong, because the men who founded this College and those whose lives and wealth have borne it into this 185th year believed that the possibilities for goodness in our kind of society thrive on thought.

And yet in every troubled period, in every land, thought has been derided, even feared, and the thinker has been harried, sometimes even unto death. I often wonder and I am sure you will, why is this so? There must be many answers. Several seem to me worth a word here.

THINKING is an acquired taste and it is a personal thing which must be acquired by each fellow for himself. It is in this respect unlike knowledge. Someone else's thought can create and give you the power of knowledge, but no man except yourself can give you the experience of thinking. May this not be a root source of anti-intellectualism? Is it not possible that as our knowledge has pyramided and our culture has deepened with the deposit of each generation, we have become preoccupied with the processes whereby knowledge and culture are transmitted to all and have become careless, even callous, about developing the will and the capacity of individual men to think for themselves. A man who has not learned to think himself is not likely to respect that which is beyond his own experience.

And may it not be that along with their blessings as transmitters of information, entertainment and appeals, the great mass media of our day are most to be feared because they make it almost irresistibly easy for the millions within their reach to take their intellectual exercise as spectators. Are we as mindful as we might be of the simple truth mentioned by one of Lincoln's early mentors "lazy minds mean a dying nation"?

I trust I need not more than pause to remind myself that knowledge and communication are very necessary and that no man learns to think in a vacuum. We've got to think about something; the something about which we think makes a difference, and that's part of the reason why the cultivation of a taste for thinking can be plain hard work. And it's worse than that. The puzzlements which dull our appetite for thought can be perverse as well as pervasive. Ever since men have worked at thinking they have had to contend with the difficulty that many of our deepest insights seem clothed in the disguise of paradox and some things at least are apparently only to be understood by accepting the possibility that man's truth is often a product of the interplay or even of the conflict between opposites.

Beyond the fact that it can be burdensome and baffling, serious thought probably will always bear something of the disability attributed to drinking water by the alcoholic who on a friend's urging reluctantly tried a glass of it and pronounced it "interesting but never likely to become widely popular." But I suggest to you that there are other reasons than a native or cultivated distaste for the stuff that contributes to the recurring manifestations of "know nothingism" in public life.

I believe the central difficulty is the fact that thought is not enough. It is necessary and it is of the utmost importance that it be as informed, as sustained and as good as our brains permit, but, I repeat, thought alone, however good, is not enough. Lest there be any momentary misunderstanding, let me say that I believe most practitioners of thought have a more profound and abiding understanding of this fact than do their detractors.

We live on an earth and in a universe (whatever that wonderful word may some day turn out to mean) where no man can know enough to be wholly right or just about anything or anyone. And yet all human experience seems persistently to suggest that the duty rests on us to try. That's quite an order for a man, as many of us have discovered on awakening at three or four a.m. in the night. As you must already have discovered or begun to suspect, it is a world of ceaseless and contagious troubles, where few men are evil by their own lights but where enough evil is generated daily and where so much of life's meaning remains undisclosed that there has never been a time in recorded history when men have not known the need of a faith which transcends the bounds of their experience. We have talked here before and we will again of that unbounded dimension of life known as Faith, but today I want to relate the work of thinking to a more earth-bound quality of human strength that quality in a man we call maturity.

I SPEAK of maturity as that ultimate selfdiscipline which rules a free man. It, too, like the power of thought, must be won by every man for himself. It is a quality born of growth and as no other, it measures at every stage the fulfillment of an individual as a human creature regardless of all else. It embraces the intellect, but it is much more. It cushions and beds the sharp edges and brittleness of thought in humility, loyalty, cooperation, good manners and the moral sensitivity of a good man. Maturity in man at his highest is not a substitute for the substantive works of reason and faith but is, I think, that condition of man in which those two sources of power prosper best.

There is another nice aspect to this quality which stamps it as peculiarly hu- man —it is always short of perfection. None of us, however old or wise we grow, is ever always in all ways mature. Each of us at many points is supported in adver- sity or saved from folly by the maturity of another. As a value to be shared, it is the deepest duty of the parent, the daily work of teacher, coach, doctor, lawyer, minister and administrator, and the opportunity of roommate, teammate, of every friend to help the other fellow measure up in a bad moment. As a self-discipline, it is perhaps at once both the most manly and most God-like of human graces.

Many human qualities are best seen in contrast and this is surely true of maturity. Maturity in a man is a quality of low visibility as compared with immaturity. When you stop for a moment to think about it, is there anything easier to spot or anything less comfortable to have close to you than a person suffering from chronic immaturity? Such a person not infrequently mistakes some form of power muscles, money, lungs, press, politics, or even intellect for Tightness. And such a person, whatever his or her power, is usually a self-advertised, unhappy, harried creature beset both by men and nature and comfortless in either salary or soul. He is at best a nuisance to be borne and at worst a peril to be met. His words, his politics, his loves, his hates, his mates, are extremities of one sort or another. He never grew up as a man to the world around him.

There are factors of time and circumstance in this matter of becoming mature. Up to now because of your youth and your place in the family, you have not been expected to make the synthesis which produces maturity from its component ingredients. You have met progressively exacting expectations of integrity, courage, perseverance) resourcefulness, manners, and intellectual interest. You are already required to know and honor the broad boundaries of right and wrong; you ought to have some sense of the role of cooperation, loyalty, humility, generosity, even of idealism and faith in this business of living and learning. But to borrow from the lament of the dameless sailors in the musical, South Pacific, the maturity you now seek is "What there ain't no substitute for" and this, also in the words of that robust song, we know "damn well."

MAY I broaden the focus with these few closing words. Maturity is one of those prime personal qualities which seems to have its close counterpart in the national character of a people. Nothing within the power of man is more important today than the measure of maturity which Americans contribute to their national character. The time factor is so Dressing that the outcome cannot be totally assigned to you either in rhetoric or reality, but I do believe that you will have the really great experience of crossing the threshold of maturity in the company of your country.

This powerful, young nation has recently had the sobering experience of falling heir to an inheritance of world leadership it neither sought nor foresaw. And, as you may have heard, the inheritance taxes have been something awful!

In truth, it was a responsibility for which America was not well prepared. As a nation we have never lacked the courage, the conviction and the resources to be strong and in the past our security could be measured by our strength. National security in such terms was a relatively simple, straightforward kind of thing. But in this riven world where destructive power on both sides is now measured in astronomical terms, the old concepts of security through greater strength may already have lost much of their relevance. As needs remarking more often, if your enemy's 10,000 bombs can destroy you, your 20,000 bombs may not provide much added security. In this kind of a business the best answers no longer fit the questions very tightly.

Moreover, in a world of some sixty selfconscious, sovereign nations the best answers of any foreign policy can never be better than "best bets" and we know how hard it is even in horse racing to. get people to agree on what is the best bet. We also ought to know that in international affairs, as with horses, indeed, as with all life's uncertainties, even best bets are sometimes lost.

It is when best bets are lost that men are separated from the boys. The immature are dismayed with disappointment and they demand answers which promise quick, sure, painless solutions. The immature are sure that only a knave or a fool (and in that order) could have made a losing bet. The mature mind resists the search for panaceas and scapegoats but out of desperation and darkness the hue and cry is once again raised against the human intellect as a breeder of evil and error. As we are again learning, it is a phenomenon which transcends nations, parties, interest groups and factions. It is nothing less than man against himself.

A liberating education stands wherever this issue is joined. It invokes the power of thought to make better that which will always be imperfect and it matches the growth of power in a man or in a nation with those qualities of maturity which permit a human creature to live fruitfully and meaningfully in a world where he can only ceaselessly seek to be true to himself, to be at terms with others, and to be as one with whatever Maker life ever so dimly reveals to him.

And now, men of Dartmouth, as I have said on this occasion before, as members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such.

Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are, it will be.

Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you.

We'll be with you all the way, and "Good Luck!"

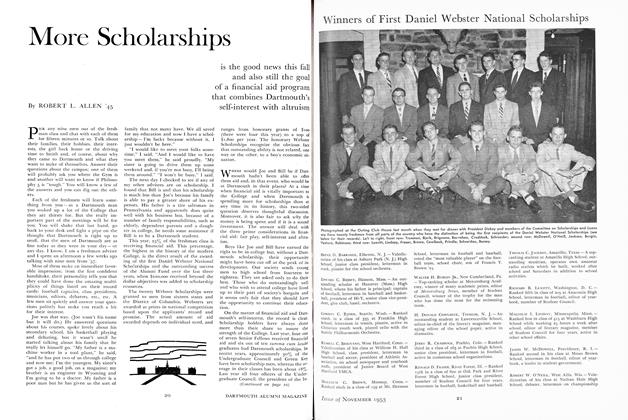

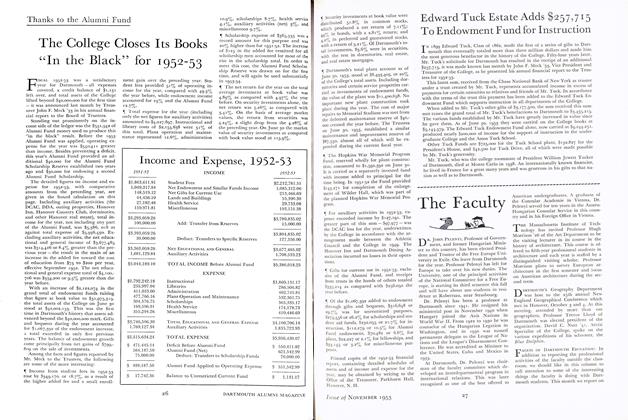

A FULL HOUSE IN WEBSTER HALL HEARS PRESIDENT DICKEY'S CONVOCATION ADDRESS

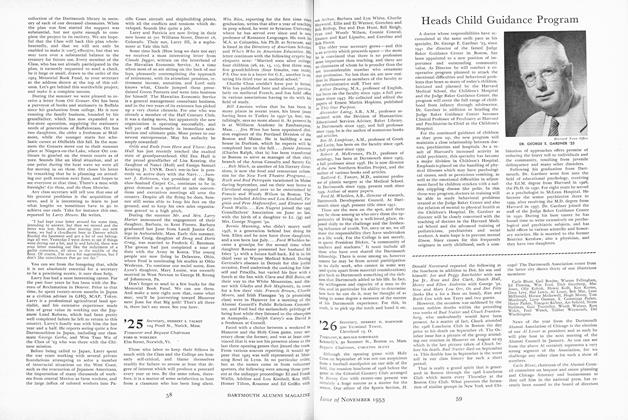

A PRESIDENTIAL GREETING for each incoming freshman was part of the matriculation process for the men of 1957. President Dickey is shown here, in the 1902 Room in Baker Library, with Chiharu Igaya of Nagano Kew, Japan, who was a member of the 1952 Japanese Olympic ski team.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMore Scholarships

November 1953 By ROBERT L. ALLEN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1953 By ERNEST H. FARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

November 1953 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

November 1953 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, CARLETON BLUNT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1916

November 1953 By F. STIRLING WILSON, C. CARLTON COFFIN, H. CLIFFORD BEAN -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

November 1953 By C. E. W.

Article

-

Article

ArticleCollege Delegates

November 1941 -

Article

ArticleAviation Cadets in Training at Kimball Union Academy

May 1943 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah for –

JUNE 1959 -

Article

ArticleDorms become official

APRIL • 1987 -

Article

ArticleAssistant Professor of Government Thomas M. Nichols:

May 1994 -

Article

ArticleWestern Pow Special

November 1938 By ROBERT B. MacPHAIL '28