In addressing the Dartmouth alumni at club and association dinners in recent weeks, President Dickey has had opportunity to state some of his views on the relation of American higher education to our national security.

"If the security of our free society is truly in our hands to lose or to save, and I believe it is," he said, "nothing is more important than for us to ask ourselves insistently the most ancient question of statecraft 'How do we keep strong enough to be free and decent enough to be strong?' " Declaring that each society must answer this question on its own terms and on all fronts of life, he confined his own answers to that part of the front held by the nation's institutions of higher learning.

There are three ingredients of national strength that depend largely on the work of higher education, President Dickey said. These are "(1) A science and technology which must always be first rate. There is no provision for second place, let alone honorable mentions, in modern armaments. (2) Top quality in all respects in those who handle the daily work of this Republic's most vital public business it foreign affairs. (3) A full measure of maturity in the home communities of America in facing a world of ceaseless and contagious troubles."

It may still be true that an army "marches on its belly," President Dickey added, "but the striking might of any nation today rests on the scope and strength of its industry. And deep within all industry is the ultimate source of its power knowledge of the physical universe. This is why in a great and real sense the daily work of the scholar, 'the business of knowing,' is an indispensable ingredient of national security.

"But it alone is not enough. The striking might of the major industrial powers is already such that those who know most about it doubt whether this civilization can survive its use.

"So far at least as we are concerned, any chance of escaping this God-awful gamble largely depends, I think, upon the other two ingredients.

"How else in America today can we have these three things on an organized, sustained and national basis except as they are bred and nurtured in those great educational enterprises which we know as our colleges and universities?

"And yet," President Dickey continued, "today there is, in some quarters, as there often has been in the past, a distrust of the scholar and those tools of critical thought with which he does his work.

"Let us be clear about one thing higher education is not immune to error and even evil; it has its share of fools and knaves, but taking into account the nature of its business, the maintenance of a free market for the evaluation and exchange of ideas, it also has over the long haul perhaps the best record on earth for exposing and purging any form of human fault.

"Let us face the ancient evil of subversion in its most pernicious modern form the disciplined communist member. For my part the past six years have fortified the position I took in 1947 that I would not knowingly be a party to employing a person who accepts the discipline of the communist party. Such a person is disqualified for service in an American educational enterprise because he presumably accepts the obligation of membership in a conspiratorial group committed to the use of deceit and deception as a matter of policy.

"The business of higher education will prosper only if it is carried on by men with honest and independent minds whose position before the laws of our society is such that they have no need to take refuge in any American tribunal behind a privilege against incrimination by their own words.

"Any governmental authority which finds it necessary through proper procedures to identify and punish unlawful acts of subversion will have my support and, I am confident, the support of every responsible institution in the land.

"But let all who applaud such an expression of manifest duty ask themselves whether they are prepared to honor the performance of, let alone share, the daily but often less manifest duty of protecting the independent-minded teacher from the foul penalties of incrimination by recrimination and insinuation.

"If both these duties are well met, higher education will remain the bulwark of our national security. If either is ever in serious default, the future will pass, as it ought, to other hands."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

March 1953 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleEducation for What?

March 1953 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Article

ArticleThe Responsibility of Management

March 1953 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Article

ArticleHome Thoughts On Europe

March 1953 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR. 48 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

March 1953 By RICHARD M. PEARSON, ROSCOE O. ELLIOTT

Article

-

Article

ArticlePUBLICITY FOR THE CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATION

May 1917 -

Article

ArticleCAMPUS NOTES

June 1921 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH CLUB OF DAYTON, OHIO, ESTABLISHED

November 1921 -

Article

ArticleClass Reunions

January 1946 -

Article

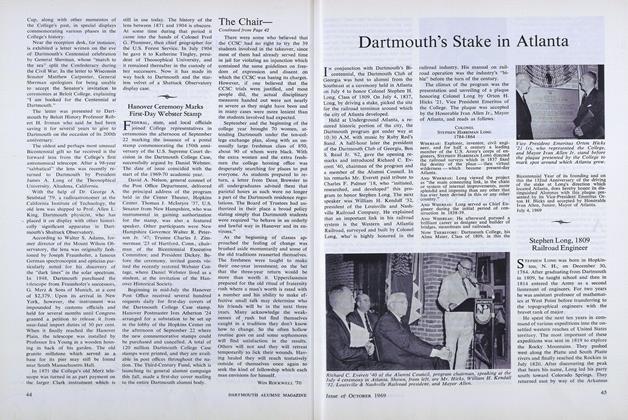

ArticleDartmouth's Stake in Atlanta

OCTOBER 1969 -

Article

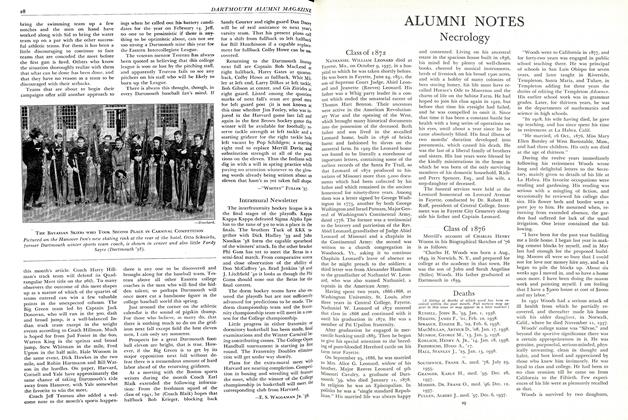

ArticleIntramural Newsletter

March 1938 By E. S. Waggaman Jr. '38