PRESIDENT OF THE INLAND STEEL COMPANY

I THINK that fundamentally I am here as a living example of an industrialist who believes that management should be articulate. I am here to try to practice what I try to preach. I hold the deep conviction that the modern American business man must know what he believes about things and must stand up and "let 'em have it."

When people ask you what you think, I think you must answer to the best of your ability. And then I think you must take the scrubbing that comes from good minds that challenge the things you say. Tomorrow, when we have our question period, I'm not so much concerned about whether I make answers that satisfy you, but I am concerned that I make answers that satisfy me, and thus develop my own personal philosophy.

Also practicing what I try to preach, I am here without manuscript I'm just going to open the faucet and see what happens. When you get to my age in business and stand in the overhanging shadows of compulsory senility you will recognize the importance of still being yourself, and I think that people are getting to be a little bit suspicious of the ghost-writer whose speech the man reads when he can't even pronounce the words, with allusions to Plato and Aristotle when everybody knows he doesn't even know in what language they wrote. And, at least if you stand up and talk as I am talking tonight, you do put the stamp of integrity upon what you say. Whether people like it or not, they know that it is you.

I commend this to the college senior who is about to enter business. If you believe that what I am doing tonight is the right thing for me to do and you plan to get into business, start now to get ready to do this when you've come to my age. You can't start too soon. Think about it. I don't know why it is but the senior in college who is so eloquent in the bull-session in the dormitory is tongue-tied the minute you put him in front of an audience not composed of his buddies. It's the same thing. I don't know why a business man that swoops in on a customer like a tiger seizing a bullock can't get up and tell people about free enterprise. It's more important to him than selling his merchandise. So I say, if you want to survive in the business world that lies ahead, you've got to be articulate from now on. You'd better start now.

I'm here to talk about free enterprise because I believe in it. It seems to me that socialism is no longer a theory. It has been tried and found to be a desolate way of life. If you don't believe that, go to England. Go to any of the other countries that are disintegrating and are kept in being solely by the life-blood pumped into them from the dynamic free-enterprise system of America. I am pragmatist enough to be lieve that what works had better not be tinkered with. No longer is socialism the thing that pious people yearn for without knowing what it is. The laboratory of world events disproves the effectiveness of socialism, and I say that the free enterprise system that's practiced in the United States has brought greater well-being to our people than any other system that has ever been tried. And that's good enough for me to know until we get something better.

I like tonight's title. It's always a good thing to know what your title is if you're going to speak and to try to let what you say bear some physical resemblance to it. My title is "The Responsibility of Management." I like both of those words.

Let's start with "Responsibility." That's the true note to strike today in business. Modern business executives who hope to preserve the system of free enterprise must at all times have an awareness of their social responsibilities. I can't define free enterprise for you I've been trying to do it for a great many years. There are a great many things in life you can't define. One, for example, is character. I've been trying all my life to define character. I know it when I see it, but I'm all through when I've said "character." It's character. But free enterprise goes something like this: It is a system in which the decisions are made by the many and not the few, and in which the decisions are made by those who have a sense of their responsibilities to others.

I would like, incidentally, if I might, to pause for a moment. This is as good a time as any to make one correction. As I entered the Inn tonight naturally my first act was to try to buy a copy of the oldest collegiate newspaper in America. I laid ten cents on the desk and was surprised to get five cents back because there is so little you can buy for five cents these days. But, as I opened the sheet and found that I had been done the honor of comment on the front page, I was startled to find that this ancient institution of great reputation had, for the first time in all its great history, made one error. There were four words left out in one of the sentences quoted from me which distorts the sense. I assume it was inadvertent, but I am skeptical after the reference to my Harvard background in the same article. The quote is, "God did not put man on this earth to live the good life." What I said was, "God did not put man on this earth for production alone but to live the good life."

And that constitutes my viewpoint toward the question of responsibility. Production, as I conceive it, is not an end in itself; the whole purpose of the free enterprise system is to serve mankind, and each decision taken in the business world, and each policy established, must be tested as to whether or not this action, this policy, not only promotes the interests of the company but promotes the interests of society.

Then I like the word "Management," the responsibility of management, and I prefer tonight to treat that perhaps in a rather technical sense, as a reference to the class to be found in American industry today known as "Management," which I happen to represent.

In older- days the proprietor ran every business, and that was a fine thing because the man whose blue chip is on the table is very careful with it, and the proprietor, who saw all of his security in life present in the business that he managed, was an awfully careful custodian. But, as American business has grown, the proprietor management scheme has given way, and today, whereas there are men who come from owning families to be found in almost every great company, if they are there you may assume that they have survived the competition in spite of their handicap and are worthy in themselves.

Companies such as I have the privilege of heading have stockholders in every state and employees in perhaps half of them, and there is no single group of owners who own as much as 10% of the common stock. And it is probably right, certainly the best thing for the organization, that a man should be chosen to head it who represents the special class of management, but it is equally important that that man have his blue chip on the table in the proprietary sense. No management man of my generation can accumulate great wealth. I've been at it a long time and have been totally unsuccessful. But I will say that the savings of my life, complete, are in the common stock of my company. So, to the extent that I am able as an individual, I put as a stamp of integrity upon my own efforts the fact that I have endeavored to stimulate the proprietor-relationship by risking everything that I have on the decisions that I make within and for the company.

Now, that is the group to which you men may aspire who plan to go into business. You will be hopeful, I assume, that ultimately you may enter the management group, and it is the great field of endeavor for able young men today which distinguishes our country from those countries overseas. In most of the European countries, where I now have some acquaintanceship with industry, the management class, as we know it, is only just beginning. The job, today, of the manager is to be somewhat the umpire among the varying interests that are to be served by a great company: the owning interests, the stockholders, the workers, and the public who receive the goods of the company.

THE outside problem of public relations that we hear a great deal about is exceedingly complex and difficult. I have never seen any man propose a program for public relations that any other man liked. I have never seen anybody write an advertisement for a newspaper that was liked by anybody except the man who wrote it. We cannot agree on what to say to the public nor how to say it. That is probably our strength. It is probably the diversity in America that is our strength. It would seem perfectly clear that it is the job of the businessman to endeavor to interpret—as I am trying to do for you tonight—interpret the business to the workers, the people within the company, and to the public, those on the outside.

In all this great field of human relations I point out to you the importance of the liberal arts training. I know its limitations I am liberal arts trained myself and I know that there are limitations in the liberal arts training as contrasted with specialist training. The limitation is that you and I think philosophically. We are not trained in precision thinking, with the same discipline that the men are who are trained as scientists and engineers. No one of us could have all of these disciplines but everybody should have some combination. It's a strange thing but we have spent vast sums of money in industry for research into the nature of matter and we have spent only paltrv sums on the nature of man. We know what creates friction when one piece of metal rubs against another and generates heat. We know why it creates heat. But when two men work along side each other and start each day by trying to knock each other's block off and the friction has developed a little heat between those two people, we don't know the answer.

The problems that confound industry today are not the unsolved problems of technology but the unsolved problems of human relations. I look to the oncoming generations of men trained in the liberal arts to have imagination, to really try to find an answer to these unsolved problems of human relations. And I want to point out again that it is the duty and opportunity of the man trained in the liberal arts to learn to speak and write the English language. You may have the best idea in the world, but if you can't tell somebody about it, it's ineffectual.

IN conclusion, I think the businessman, if he has any sense of leadership, should stand up and be counted, and say who he is for and why, in order to advance the general debate. And I think the businessman should take, voluntarily, his part in government. If you will pardon a personal reference, I was suddenly summoned into public service in 1948 by Mr. Paul Hoffman. He called one afternoon at a quarter of five and said, "Would it interest you to know that you're going to Paris as first steel consultant for the Marshall Plan?"

I said, "I can't possibly go. You know, the indispensable man."

He said, "Take all the time you want as long as I hear from you at 9:00 o'clock Monday morning."

So, at 9:00 o'clock Monday morning, I said, "O.K. I'll go if I don't have to fly the ocean."

He said, "You won't."

So I flew the ocean, and I arrived in Paris, as I've often said, when the ECA program consisted of Averill Harriman and the two French plasterers who were remodeling the office. And I've been at it ever since. I've been back five times. And I'm presently engaged in trying to develop interest in this country in the Schuman Plan and on the whole question of aid.

I happen to believe that the Marshall Plan was necessary, though badly administered, and, nevertheless, fulfilled its purpose. It snatched Italy back from Communism, it steadied France and it brought hope to people all through Europe. I think its job is done. I think we must now know why we are in Europe. The difficulty of our foreign policy, it seems to me, is we have no basic philosophy. I think the only thing the American people mean to be committed to is "what is best for American security." Therefore, every step in Europe must be measured by that standard.

Here are two things that bother me. The Schuman Plan is supra-sovereign ty. The United States, by its dollars, has induced six nations to surrender sovereignty, and we wouldn't do it ourselves. That's an ethical question that bothers me. By what right do we compel others in Europe to surrender sovereignty when we are not prepared to do it ourselves? We have used our dollars to compel European nations to drop restrictive practices and reduce tariff barriers, and we do not do it ourselves. We are raising tariffs against those of whom we make the demand that they shall reduce tariffs, and that presents an ethical question.

Back of this lies the whole dilemma of whether, when we give dollars to Europe, we have the right to intrude into their internal affairs. People pound the tablethey did with me and say, "But they're our dollars!" It may be true, but it's an awful responsibility thus to buy the way to dictate. We fought two wars to eliminate dictators from the world, and are we to establish a dollar dictatorship over the world? We are denying self-determination to the European nations who receive our bounty, and at the same time, in Africa, we are demanding that they grant self-determination to oppressed peoples who do not know democracy.

I do not pretend to know the right or the wrong of these great questions, but it does seem to me that the time has come for the American people to know why we are doing what we do, and for that end we need a great, vital, vigorous debate to sweep across our country on all of these questions in the hope that out of it may come some common denominator of understanding to which all people may subscribe.

May I close by saying, I really believe this is a great time to be alive? Great events are on the march in the world. This is no time for defeatism. This is a thrilling time, and anybody who believes in things and who thinks he would like to see a life of happiness and contentment ahead may join the battle. I think the American people have never been greater and they are great because our way of life is so conceived that it releases the utmost of potential that God has given to each individual. And the essence of that is freedom. We hold that in trust for the entire civilized world. God give us strength to preserve it and give you young men the strength to do better than we did!

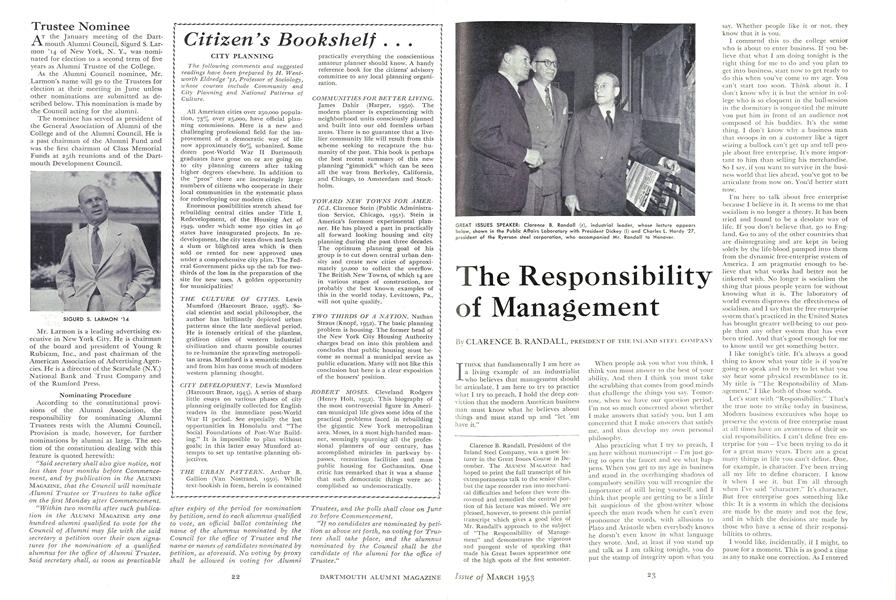

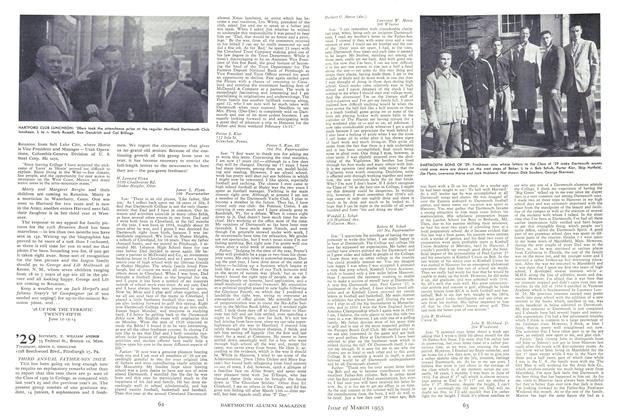

GREAT ISSUES SPEAKER: Clarence B. Randall (r), industrial leader, whose lecture appears below, shown in the Public Affairs Laboratory with President Dickey (I) and Charles L. Hardy '27, president of the Ryerson steel corporation, who accompanied Mr. Randall to Hanover.

Clarence B. Randall, President of the Inland Steel Company, was a guest lecturer in the Great Issues Course in December. The ALUMNI MAGAZINE had hoped to print the full transcript of his extemporaneous talk to the senior class, but the tape recorder ran into mechanical difficulties and before they were discovered and remedied the central portion of his lecture was missed. We are pleased, however, to present this partial transcript which gives a good idea of Mr. Randall's approach to the subject of "The Responsibility of Management" and demonstrates the vigorous and pungent style of speaking that made his Great Issues appearance one of the high spots of the first semester.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

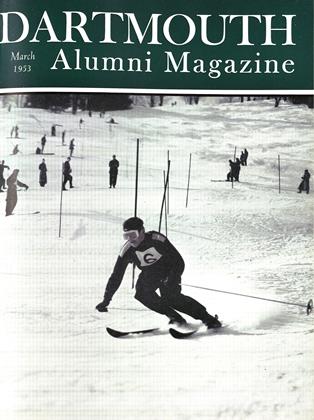

March 1953 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleEducation for What?

March 1953 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Article

ArticleHome Thoughts On Europe

March 1953 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR. 48 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

March 1953 By RICHARD M. PEARSON, ROSCOE O. ELLIOTT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

March 1953 By ENS. SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMOND J. MORAND III