If the fact that Dartmouth ran two lotteries to help sustain it during its infant years should come as a surprise to some of the alumni, it is only because their acquaintance with Dartmouth's early history has not ventured beyond the lore of rum and Indians, of Eleazar, John Ledyard and Black Dan. But lotteries did play a part not a major part but at least a vital one.

The story of these lotteries appears in quite some detail, but with a few errors, in Frederick Chase's monumental history with its wealth of material on the College's early years, published in 1891; and it also appears in an extremely condensed version in Professor L. B. Richardson's fascinating volumes published in 1932. Incidentally, any alumnus who gazes upon the green from the Inn porch, or who evokes that pleasant scene in his mind's eye wherever he may be, will appreciate more of the meaning of what he sees if he reads Richardson's history, still readily available, and. learns how the "horrid wilderness" was transformed into the tranquil scene before him. It deserves the plug.

This article is based on source material including data turned up during the last few years. There are still a few missing gaps and a few unresolved problems, but when it is considered that of the thousands of American lotteries adequate informa- tion may be had of only a small minority, and some are known only because tickets were lost and advertised for, we are lucky to know so much of those that here concern us.

Not only all the Ivy Group colleges except Cornell, but very nearly all the prerevolutionary American colleges as well as many of a later vintage ran lotteries. In some cases, lotteries were run to establish the institutions. The first of several whose purpose was to aid the founding of the present Columbia University started the procession in 1746, to be quickly followed by Yale's one and only excursion into this field in 1747. Later came the first of five for the College of New Jersey (Princeton), followed by the first of seven, with Benjamin Franklin one of the managers, run for the academy and college later to become the University of Pennsylvania. Other lotteries helped to establish or to strengthen those institutions known now as Brown, Dickinson, Harvard, Rutgers, William and Mary, Williams, and the Universities of Maryland and Delaware. There were still more.

Since the need for the Dartmouth lotteries arose from the exigencies of erecting Dartmouth Hall, a few facts connected with its building should be borne in mind. The date usually associated with it is 1784, but in that year it consisted of not much more than a hole in the ground and not the first hole at that. Eleazar Wheelock brought with him in 1770 the plans for the structure, even larger than it turned out to be. For him it remained a dream.

How can one believe that on the green criss-crossed with footpaths there once stood forest giants 100 feet to the first branches and up to 270 feet tall? Wheelock and his laborers had no bulldozers to clear the land, to dig and chop and pry the massive stumps out of the reluctant earth, and yet the work was done. It is a heroic story. The frames of the temporary buildings were nearly completed when they had to be dismantled and moved when one well and then another dug scores of feet failed to produce water. And then winter came too soon.

The snow lay four feet deep upon the mass of fallen pines too green to be burned, and as late as June 13 Wheelock found the ice six inches thick under the chips. Yet, by the second Commencement, in 1772, came the events that will never be forgotten as long as Dartmouth stands. Governor Wentworth with a brilliant assemblage arrived from Portsmouth, the ox was roasted and the "hogshead of liquor" I hope it was rum created a never-to-be-repeated scene that grows with the years.

Later that same year Wheelock petitioned the New Hampshire legislature for a lottery. When it was turned down early in 1773 he went ahead anyway with the excavation for the future Dartmouth Hall on its present site. But along came the Revolution with its attendant tribulations. Eleazar had passed to his reward five years before the hole was enlarged in 1784.

Three years later, Commencement exercises were first held in "the new and elegant edifice," reported thus in the Connecticut Courant's issue of October 8, 1787: "The philosophic mind is charmed with the view of that flourishing and fair literary institution, in our northern hemisphere, and from its rapid progress, anticipates its future usefulness and glory."

Yet the practical mind saw that though the building at last was roofed, it was far from ready, and the work which had progressed by fits and starts again came to a halt. In September 1788, the Trustees voted that the contractor should not endeavor to render the edifice habitable "the ensuing winter unless providence open a door for further & other resources for that purpose than what are now within view of this board." It was not until the summer of 1792 that the structure stood completed.

There were several potent reasons why Dartmouth for that period attracted a large student body, but one of them must have been this impressive building whose replica still holds the heart of the College as the original did then. In 1791 Dartmouth graduated more students than did Harvard, Yale or Princeton, and in the decade beginning that year the only one of these colleges to surpass her in the number of graduates was Harvard.

WITH this background we are now ready to see what the lotteries were and what they accomplished. Tabulated data will appear in a footnote at the end of the article. The Trustees voted on March 31, 1784, to begin the erection of the edifice as soon as £2,000 should be pledged by subscriptions. But pledges were hard to collect, even when it was announced at the end of the year that country produce such as beef, pork, neat cattle, and grain of all sorts would be accepted in payment. Meanwhile, on September 19, the Trustees resolved to petition the New Hampshire Legislature for a lottery and appointed President John Wheelock to present a memorial for that purpose.

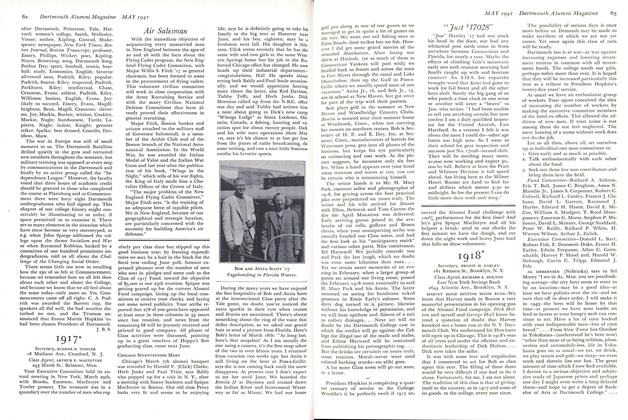

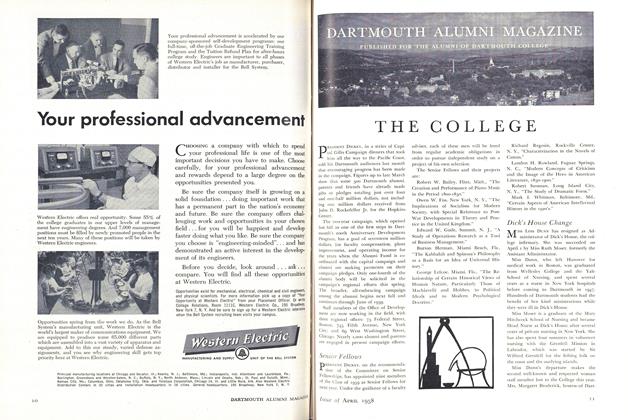

An act granting the lottery was passed on November 3, 1784. It authorized the Trustees to raise £3,000 by this means, clear of expenses, in silver and gold, the lottery to be drawn within three years. The five managers named lived in the more populated part of the state three in Portsmouth and two in Exeter. Advertisements of the scheme, giving a table of the prizes, appeared in various New England papers, repeated many times. The earliest insertion of any of them was in the November 18, 1784, issue of the NewHampshire Gazette of Portsmouth. Of the $12,000 that would come in if all the tickets were sold, 19,420 was to be paid out in prizes; the balance, less expenses, represented potential profit to the College. If the tickets should sell quickly, one scheme after another could be advertised and drawn until the requisite amount was raised.

Interest in lottery speculation all over the country came and went in waves, the conditioning factors being partly economic and partly psychological. Hardly a worse period could have been picked for the Dartmouth lottery, except during the Revolutionary years when even the United States Lottery backed by the Continental Congress turned into pretty much of a fizzle. Prostration from the war hung like a pall for years if not from the destruction of property itself, then from the debacle of the Continental paper money. Everywhere barter became a common means of exchange. Even in the populous centers of Boston, New York and Philadelphia, if lotteries were run at all they had tough sledding bogged down by protracted delays or abandoned.

An announced date for the drawing to commence on June 7, 1786, failed of its purpose to attract the last-minute buyers. Finally it was decided the only way for the lottery to succeed would be to conduct it from Hanover and sell the tickets if need be for country produce exchangeable for local labor and building supplies. Supplementary acts for this purpose were passed, one on January 12, 1787, and another on September 28, 1787. New managers connected with the College, close at hand, were appointed and the amount to be raised was reduced to £1,800. In the College histories these acts are treated as constituting a new lottery, but they really were a continuation of the first.

At any rate, the tickets in the cancelled 1784 scheme that had been sold for cash were redeemed or exchanged for tickets in the new one. The managers announced a practice common enough, of two integrated schemes, in which many of the prizes in the first consisted of tickets in the second. Not a single newspaper or other record with the schemes of these two classes has been found so far, nor has even a ticket been located. Until recently, it was not even known that both classes were drawn.

In the Vermont Journal for April 21, 1788, in a notice dated at Dartmouth College April 16, the managers state that they "have proceeded some way in drawing the First Class," with tickets still for sale, but that further drawing was adjourned until May 6. The object of this maneuver no doubt was to give them more time to lure timid adventurers who had held off until they knew the drawing had begun. The only known copy of the May 19, 1788 issue of the same paper contains the list of winning tickets with the values of the prizes ranging from one of 50 bushels of wheat down to 1,000 prizes of five bushels each, nearly all of which were payable in tickets of the second class.

Dartmouth no doubt then owned more wheat at one time than it ever has since or ever will again. Cattle also figured in the dealings arid among the surviving accounts are items of "a horse purchased with tickets" described elsewhere as "belonging to Lottery."

IT was a rare lottery in which all the tickets were sold before the start of the drawing. In the usual one, if the sale lagged, a desperate effort was made to avert postponement by getting one person or a group to take up a dangerous excess of unsold tickets and then those that remained were held at the risk of the institution for which the lottery was run. In one of its own lotteries, Harvard in this way won the top prize of $10,000.

A Dartmouth Trustee at this time was John Phillips, founder of Phillips Exeter Academy and one of the founders of Phillips Academy at Andover. In proportion to the needs and resources of the College during her infancy, she had no more liberal benefactor after Eleazar Wheelock himself than John Phillips. The alumni of my generation will never forget the stalwart, noble personality of Ben Marshall who addressed us so often by dint of compulsory chapel exercises. We knew he taught the religious courses but not until consulting my Aegis did I realize he was the Phillips Professor of Biblical History and Literature. The permanent support of a Professor of Divinity at Dartmouth remained one of Phillips's chief objectives.

So strongly did he feel that the drawing of the new first class should not be postponed he had earlier bought 44 tickets, 12 from Wheelock that he gave his word he would take up to 300 tickets if that many were left unsold. The drawing had already been completed by May 17 when a message was dispatched to Phillips informing him that when the drawing recommenced the previous week, 467 tickets remained on hand, far too many for the College to take without risking a possible heavy loss if it should miss a proportionate share of the high prizes. Therefore, in accordance with his offer, 302 of them had been assigned to him before the drawing began again; these were delivered to President Wheelock for safe keeping, and the numbers of the tickets were now being sent to him. With more propriety, it seems, the list of numbers should have been on its way before the wheels turned again. Be that as it may, Phillips kept his word and paid for them and the other 44 at once in negotiable funds. Thus, of the 2,000 tickets in this drawing whose success meant so much toward completing the edifice, he held 346. And the 285 bushels of wheat he gave to the College in 1791 probably came from the prizes he won by the end of the drawing of the second class.

Upon Phillips's resignation in 1793, the Trustees voted that he should be asked to sit for a full-length portrait "for the purpose of being deposited in one of the public chambers of this University, that this board the Officers and Students & others in future time may have opportunity to view the traits of the person who far beyond all others hath extended his liberality to this institution." The, portrait now hangs in Baker Library, but the legend beneath does not mention his benefactions. Sometime in future years when the College is about to name a new building she could do no better than to remember him.

The profit from this first class did provide some immediate relief but the need for funds to further the work on the edifice remained desperate. The Board voted on December 24, 1788, that the lottery managers be requested to push the sale of the second class tickets, "disposal of them being of utmost importance." One of the Trustees, the Rev. Bulkley Olcott, wrote in a letter dated the following January 13 of "the bad Situation of College affairs; ... The Subscription comes in badly: the Lottery cannot at present be got thro with: all resources fail: we have reckoned too fast and must now abide the Consequences."

A few months later, May 25, Olcott wrote again to say the College is "prodigiously rich in lands" but "prodigiously poor" in ready funds. "The present necessities of the College are great & urgent. Debts for what has been done press hard ... I see no way but our new Edifice must stand useless in statu quo, for how long I know not." Some of the College land could be sold, he said, but only at half its value, and as a matter of fact much of it was sold. Olcott went on to say "there is danger our rising, promising Seminary will almost tottally sink in its Credit & Respectability... the College is like to obtain no farther relief from the Subscription or the Lottery: they will both probably prove in a great measure, or altogether abortive."

Again, the Trustees urged the managers to use "every exertion" to sell the tickets. At the meeting on August 25, 1789, they told them to commence the drawing as soon as they should judge it expedient and that they, the Trustees, would take the unsold tickets at the risk of the College. Another year passed, and it was not until September 4, 1790, that the managers had completed the drawing and signed the prize list. The prizes were to be paid in wheat or its "cattle equivalent." Incidentally, at this same time a lottery was being run in Massachusetts for the Williamstown Free School, soon to become Williams College, in which cattle were a medium of exchange.

Chase states that the second class was finally drawn "January, 1791, in the desk of the College chapel (much to the scandal of some worthy people)." Neither Hazel E. Joslyn, Archivist of the Baker Library, who has been of great service to me in digging up records, nor I have found any basis for this statement. The date attributed to the drawing is several months late, suggestive that the source of Chase's statement was not reliable. As for some persons being scandalized, it may well have been so. However, at this time the attitude of the churches as a whole overwhelmingly favored lotteries. The point is so clear there is no use discussing it. Managers of church lotteries consistently urged adventurers interested in the furtherance of religion and morality to buy tickets.

IT is impossible to say how much profit arose from the lottery. The final balance sheets of the managers must not have survived and, worse still, a vital College general ledger for the period is missing. The "final statement" of Colonel Payne, the contractor, states that the new edifice cost £3,039.0.7, besides interest up to 1805 amounting to £455.1.0, but the sums are not broken down in such a way as to reveal what part came from the lottery. Another paper shows that Payne received £366.15.0 from the lottery managers between January and August, 1788, which was applied "towards the new Edifice."

There are many straws of evidence, but the trouble is that some point one way and others the opposite, and nothing is gained from mentioning some of them and not all. However, several are of interest in themselves because they furnish evidence as to when Dartmouth Hall was completed. The managers were busy settling their accounts in 1791. The plastering of the edifice late in 1791 was paid for, not in profits from the lottery, but in land, and other work on the interior, up to August 1792, was paid for in rents. On the other hand, in August 1792, the financier turned over £10 in specie and £14.10.0 in neat cattle "towards pay for building the door steps to the College." Now where did the cattle come from if not from the profits in cattle of the second class?

There can be no final conclusion as to the profit from this lottery until more evidence turns up. It did definitely contribute something toward the erection of Dartmouth Hall perhaps one-eighth of the total cost. Probably the profit amounted to about as much as Payne received in 1788. It may have been slightly more; it may have been a great deal less.

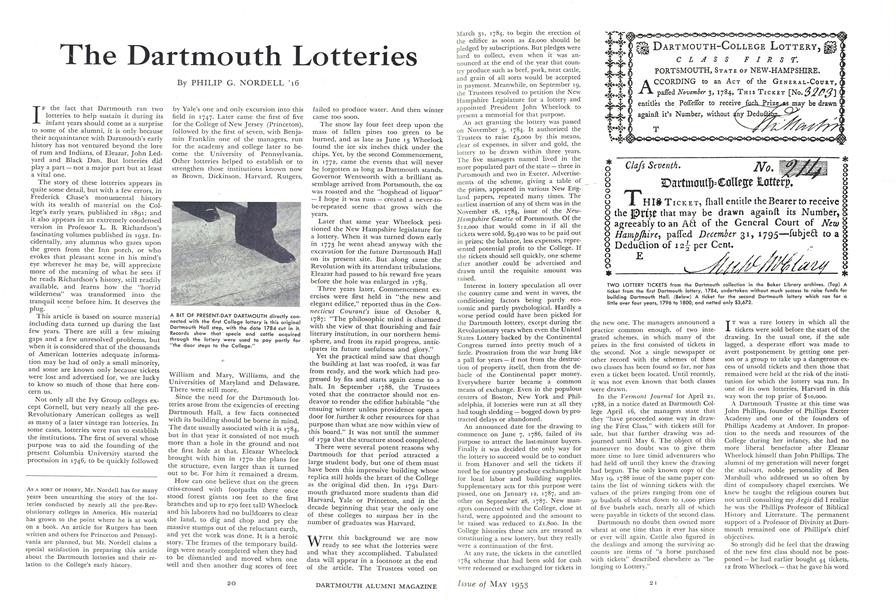

I am indebted to Harold G. Rugg, Associate Librarian, and to Halsey C. Edgerton, the former Treasurer, through Mr. Rugg, for the information that not even the foundations of the original building were incorporated into the present replica. However, Mr. Rugg believes the front door steps are those originally placed there. This being so, the only remaining appendage to the original edifice on the original site and still in use was paid for partly in cattle acquired from the lottery.

The terms of the second supplementary act, which extended the period of lottery operations for two years, had now more than run out. The need for lotteries continuing, the Trustees soon turned their eyes toward the legislative chambers again. There is far more data on the second lottery than the first, but apart from the concise details given in the note below, little need be said. As early as 1793 the Trustees began their effort to get another lottery authorized. A grant was approved by the Legislature on December 31, 1795, to raise $ 15,000 clear by lottery, with a limit of five years, on tRe strength of which seven classes were drawn before the expiration date.

The first class was first advertised in the newspapers on March 7, 1796, and the prize list of the last was published on July 12, 1800. Owing to competition from other lotteries and a somewhat sour attitude of the public toward them at this time, besides an uncommon scarcity of cash, substantial numbers of tickets remained unsold in the various classes. The drawing of unsold tickets as a rule proved unfortunate for the College.

A balance sheet submitted in 1801 shows a tentative net profit of 13,672.03. When tickets were sold on credit as they were here, it took an interminable period to wind up the last small balances; some of the adventurers skipped, became insolvent or died before they paid with consequent lawsuits. The last unsettled balances in this lottery were still dragging along in 1808. Perhaps $200 to $300 was lost in bad debts, but to counter this perhaps the same amount of unpaid prizes remained on hand. Consequently the 1801 figure must have been close to the final result.

Since the purpose of this lottery was to reduce the College debt, and since this included the debt incurred in building Dartmouth Hall, it may be said that the profit from this lottery, as well as from the first, went toward the cost of erecting the building.

Lotteries being in the doldrums in this period, the results could not have been too disappointing in view of the dismal fate of some of the others. It does seem a tremendous waste of energy to raise less than $4,000 in five years, but it must be remembered that the lotteries were run because adequate subscriptions failed, and that the load of debt, huge at that time, would be a picayune impediment today.

Two brief incidental items may be mentioned. The Rev. Israel Evans, one of the Trustees, donated to the College whatever prizes might arise from ten tickets he bought, to be applied for the benefit of the Library. The other concerns Abner Cheney of the Class of 1796. Shortly before his graduation, seeing one of the broadsides of the second class posted in an inn at Chesterfield, he tore it to pieces. It was deposed he said the lottery was "an infamous thing," that the Wheelocks "Pretended that the Colidge was in Debt But it was no Such thing But they ment to Put Mony into their owne Pockits." He signed a contrite acknowledgement and was for given.

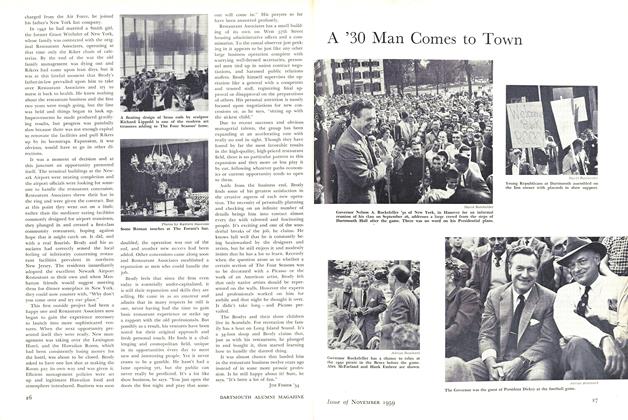

There was one lottery not connected with Dartmouth but since the tickets were printed in Hanover under extraordinary circumstances it should be mentioned. For reasons that cannot be stated here, Hanover in 1778 became Dresden, Vermont. It was arranged for a printer to set himself up in town, which he did on land a little south of the present Inn. He brought with him the now famous Stephen Daye press, on which the first printing in the British colonies within the present United States was turned out, at Cambridge, Mass., including the Bay Psalm Book, a copy of which sold a few years ago for $151,000. The story of the Dresden press by Mr. Rugg appears in the Alumni Magazine for May 1920, in which it will be seen that the tickets for Vermont's first authorized lottery were printed on this historic press during its brief sojourn in Dresden or Hanover. One of these tickets, one of four that have since turned up, is illustrated.

THE FIRST LOTTERY

Authorized by act passed Nov. 3, 1784. CLASS 1. Scheme: [Portsmouth] New-HampshireGazette, Nov. 18, 1784. Drawing cancelled. Authorized by supplementary acts of Jan. 12, 1787and Sept. 28, 1787.

CLASS 1. Scheme: Not known to exist, but it can be constructed in part from the prize list. FirstDrawn: On or shortly before April 16, 1788 (Vermont journal, April 21, 1788). Last Drawn: On or shortly before May 17, 1788 (Letter from Bezaleel Woodward to John Phillips, May 17, 1788). Where Drawn: Hanover. Prize List: Vermont Journal, May 19, 1788.

CLASS 2. Scheme: Not known to exist, but it can be constructed in part from the prize list. LastDrawn: On or shortly before Sept. 4, 1790 (Concord Herald, Oct. 12, 1790). Where Drawn: Hanover. Prize List: Concord Herald, Oct. 12, 1790.

TICKETS: A few in the cancelled First Class in Archives Dept., Baker Library. None in the later Class 1 and Class 2 known to exist.

THE SECOND LOTTERY

Authorized by act approved Dec. 31, 1795. CLASS 1. Scheme: [Concord] Courier of NewHampshire, March 7, 1796. First Drawn: June 7, 1796 (Courier of N. H., June 14, 1796). Last Drawn: June 16, 1796 {New-HampshireGazette, June 18, 1796). Where Drawn: Assembly Room, Exeter, N. H. Prize List: N.-H. Gazette, June 18, 1796.

CLASS 2. Scheme: N.-H. Gazette, June 18, 1796. First Drawn: Dec. 1, 1796 (Broadside in Baker Library). Last Drawn: Dec. 16, 1796 (Broadside in Baker Library).

Where Drawn: Daniel Gale's inn, Concord, N. H. Prize List: Courier of N. H., Dec. 27, 1796.

CLASS 3. Scheme: Courier of N. H., Jan. 17, 1797. First Drawn: June 13, 1797 (Courier of N. H., July 4, 1797, "Extra"). Last Drawn: June 22, 1797 (Courier of N. H., July 4, 1797, "Extra"). Where Drawn: "Mr. Gale's long-room." Prize List: Courier of N. H., July 4, 1797, "Extra."

CLASS 4. Scheme: Courier of N. H., Oct. 3, 1797. First Drawn: Feb. 21, 1798 (W. A. Kent's letter, Feb. 25, 1798). Last Drawn: March 12, 1798 (W. A. Kent's letter, March 16, 1798). Where Drawn: Concord. Prize List: Courier of N. H., April 3, 1798.

CLASS 5. Scheme: Courier of N. 11.. July 3, 1798. First Drawn: Nov. 22, 1798 (Courier of N. H., Nov. 24, 1798). Last Drawn: Dec. 26, 1798 (Courier of N. H., Dec. 29, 1798). Where Drawn: Concord. Prize List: Courier of N. H., Jan. 19, 1799.

CLASS 6. Scheme: Courier of N. H., Nov. 2, 1799. First Drawn: Scheduled to commence at Concord ([Boston] Columbian Centinel, Jan. 4, 1800). Adjourned to March 6, 1800 at Portsmouth by resolve of Trustees (N.-H. Gazette, Jan. 22, 1800). Last Drawn: Probably by March 18, 1800 (that being date of managers' notice of Class 7 in Courier of N. H., March 29, 1800). Prize List: Courier of N. H., March 29, 1800.

CLASS 7. Scheme: Courier of N. H., March 29 1800. First Drawn: Probably June 5, 1800, the scheduled date. "Now drawing" (Courier of N. H., June 14, 1800). Last Drawn: "Will be completed next week" (Courier of N. H., June 21, 1800). Where Drawn: "At Mr. Gale's Hall." Prize List: Courier of N. H., July 12, 1800.

TICKETS: One or more in all classes except 4 in Archives Dept. Baker Library. No tickets in Class 4 known to exist.

The Trustees' minutes, letters and other manuscripts cited, with many others not mentioned, are either in the Archives Dept., Baker Library, or uncatalogued in the custody of Mr. Max Norton, Bursar. Locations of newspapers will be found in Clarence S. Brigham's History and Bibliography of American Newspapers 1690-1820.

A BIT OF PRESENT-DAY DARTMOUTH directly connected with the first College lottery is this original Dartmouth Hall step, with the date 1784 cut in it. Records show that' specie and cattle acquired through the lottery were used to pay partly for "the door steps to the College."

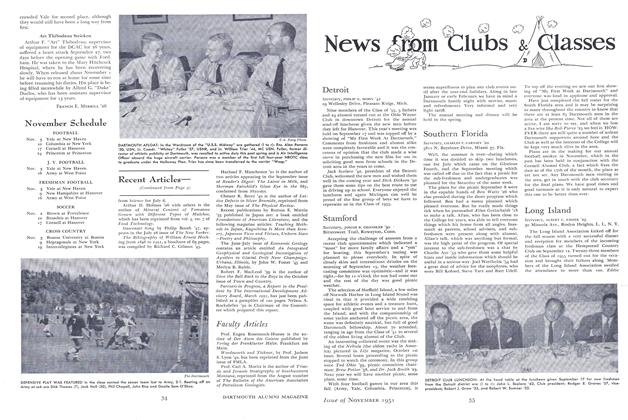

TWO LOTTERY TICKETS from the Dartmouth collection in the Baker Library archives. (Top) A ticket from the first Dartmouth lottery, 1784, undertaken without much success to raise funds for building Dartmouth Hall. (Below) A ticket for the second Dartmouth lottery which ran for a little over four years, 1796 to 1800, and netted only $3,672.

EARLIEST ADVERTISEMENT of the first Dartmouth lottery was this insertion in the "New Hampshire Gazette" of November 18, 1784. The scheme, listing prizes, appeared throughout New England.

OF SPECIAL INTEREST among early lottery tickets is this one printed in Hanover on the famous Stephen Daye press. The lottery was the first authorized by Vermont, at a time when Hanover had a double identity as Dresden, Vermont.

As A SORT OF HOBBY, Mr. Nordell has for many years been unearthing the story of the lotteries conducted by nearly all the pre-Rev-olulionary colleges in America. His material has grown to the point where he is at work on a book. An article for Rutgers has been written and others for Princeton and Pennsylvania are planned, but Mr. Nordell claims a special satisfaction in preparing this article about the Dartmouth lotteries and their relation to the College's early history.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

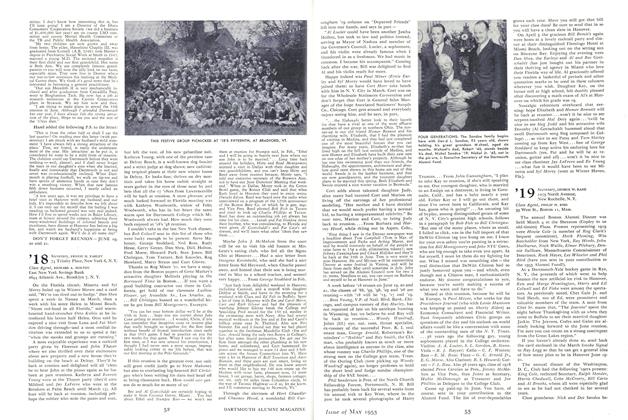

ArticleBaker's Friends

May 1953 By PROF. HERBERT F. WEST '22, SECRETARY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1953 By RICHARD A. HOLTON, ERNEST H. EARLEY -

Article

ArticleThe College Days of Sherman Adams

May 1953 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

May 1953 By GEORGE B. REDDING, F. WILLIAM ANDRES -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

May 1953 By OSMUN SKINNER, GEORGE H. PAS FIELD, WILLIAM COGSWELL -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1953 By Richard C. Cahn '53